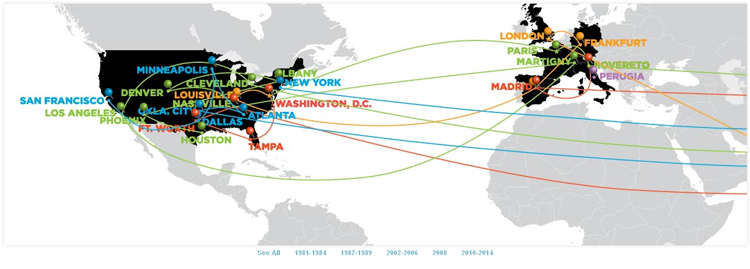

(Left) Vincent van Gogh, The Road Menders, 1889. Oil on canvas, 29 x 36 1/2 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1949 (Right) Vincent van Gogh, The Large Plane Trees (Road Menders at Saint-Rémy), 1889. Oil on fabric, 28 7/8 x 36 1/8 in. The Cleveland Museum of Art. Gift of the Hanna Fund, 1947

Vincent van Gogh has been popular in headlines around the world this week, after it was confirmed that a painting stowed in an attic for years is an authentic van Gogh original.

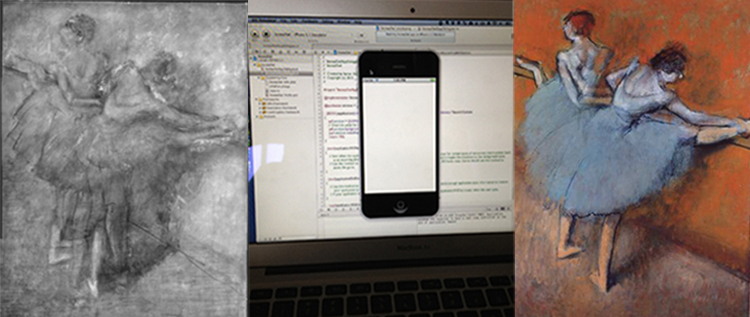

The revelation begins an interesting dialogue about the impact of science and technology on the art world. There’s no doubt it’s opened innumerable doors of opportunity as a medium, but it’s also created an opportunity for new questions to be asked. In the case of the discovered painting, technology (among other resources) helped us answer a question. Is this painting by Vincent van Gogh? Yes, we can decidedly say it is.

But in the Phillips’s upcoming exhibition Van Gogh Repetitions, science and technology may leave us with more questions than answers. We’re able to examine van Gogh’s works at a level never before known. We can tell what elements make the blues hiding inside the gap of Madame Roulin‘s sleeves vary from portrait to portrait, or how many millimeters the distance between her eyes changes, but it can’t tell us what compelled the artist to make five paintings of the same woman, or which changes he even intended to make. Were some just error? Are there more limbs on a tree in the background of the Phillips’s The Road Menders than there in the Cleveland Museum of Art’s The Large Plane Trees (Road Menders at Saint-Rémy) because it was more true to life, or because van Gogh found it more visually appealing?

As Director Dorothy Kosinski notes in this Washington Post article by Emily Yahr, art history isn’t static; “there’s so much that’s changed and continues to change, and it’s a wonderful revelation—especially to the layperson—of the importance of the work we do.”

Amy Wike, Publicity & Marketing Coordinator