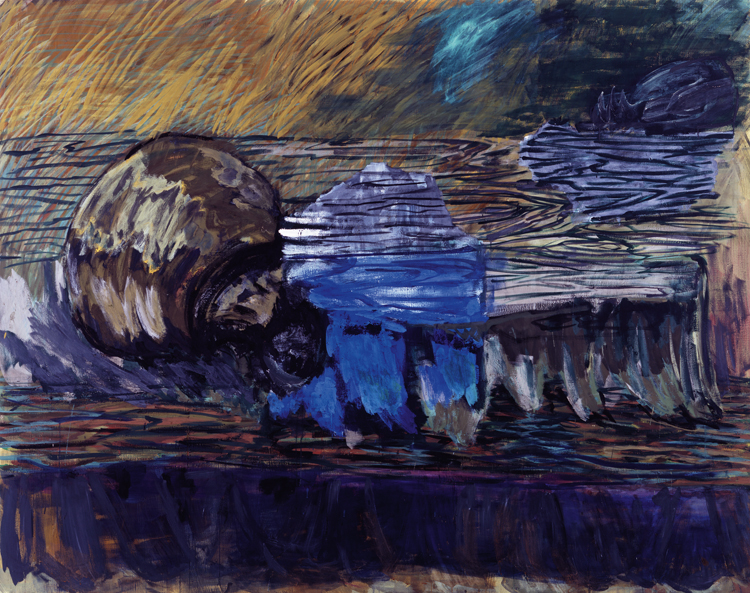

Per Kirkeby, Untitled, 2006. Tempera on canvas, 78 3/4 x 98 1/2 in. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York, London, and Berlin

Yesterday, I mentioned Per Kirkeby ‘s use of tempera. He’s not the only artist to switch to a water-based medium due to a reaction to turpentine. Peter Doig, who delivered a Duncan Phillips lecture and showed a small exhibit of chubby birds at the Phillips back in 2011, switched from oil to distemper on linen as he was trying to get away from long-term effects of paint solvents. This caution despite having a studio in Trinidad, a pavilion really, that he can open up to the air.

In this case, tempera does not mean cheap poster paint but refers to an oil-modified egg tempera. Canvas is inappropriate ground for pure egg tempera, which needs a sturdy, inflexible support like panel. Besides, even with a dedicated studio assistant separating out all those egg yolks for that much paint, the process of preparing the paint is grueling. There are dozens of recipes for a whole egg / oil emulsion tempera that can more easily be made in large batches, but there is also a shortcut. You can grind dry pigment with water into a paste, then mix it with store-bought Sennelier Egg Tempera Binding Medium, which contains egg and drying oils.

The advantage of this medium, in addition to being less toxic, is that it dries quickly, so a painting can be worked on and completed, important if you feel your time on earth may be limited. The disadvantage is that a painter thinks one way for oil painting, and another way for tempera; it is not just a change of painting medium but a sudden shift in painting thinking. Artists, when they think of an image to paint, frequently see it in a certain medium and the attendant steps required to go about achieving the desired effect; artists think in medium. It would be like a composer thinking in the range and possibilities and limitations of musical instruments when writing a score (unless you’re John Cage). Tempera may prove to be only a temporary break for Kirkeby.

Ianthe Gergel, Museum Assistant