In this series, Education Specialist for Public Programs Emily Bray profiles volunteers within the museum. The Phillips Collection volunteers are an integral part of the museum and help in many ways: greeting and guiding guests through the museum, helping with Sunday Concerts, assisting patrons in the library, helping out with Phillips after 5 and special events, and so much more. Our volunteers offer a wealth of expertise and experience to the museum, and we are delighted to highlight several them.

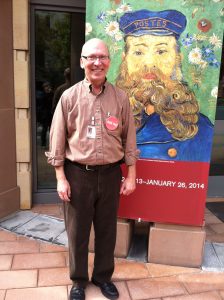

Chuck McCorkle

For volunteer Chuck McCorkle, helping people has been at the core of his life endeavors for many years, taking him to the other side of the world and to The Phillips Collection, where he has a personal connection with some of the artists in the museum’s collection.

Chuck returned in April from Sierra Leone, where he volunteered as a mental health therapist to help medical caregivers deal with their difficult, and often traumatic, work in treating Ebola patients. Chuck had been consulting with Partners in Health, providing exit interviews with medical caregivers over the phone, when they asked if he would be interested in traveling overseas to help in person. He spent about four weeks on the ground in Sierra Leone working directly with medical caregivers and local staff, many of whom were Ebola survivors coping with the loss of their own family members to the disease.

Chuck McCorkle in front of The Colosseum in Rome, Italy.

Chuck graduated with an art degree from Indiana University and received a 2 year fellowship at the Fine Arts Work Center in the 1970s. It was there in Provincetown, MA that he initially met and worked with abstract painters Myron Stout and Jack Tworkov, assisting in packing artwork, stretching canvases, and learning what it was like to be a living artist. In the 1980s, after having moved to Boston, Chuck began to see an increasing need for help to fight the newly recognized AIDS epidemic. This became a career changing event as he began volunteering on the local AIDS hotline. Soon after, he began working for the Massachusetts AIDS Bureau developing psychosocial support programs statewide. After receiving his MSW, he became an HIV therapist at Massachusetts General Hospital, again developing programs for clients, including a Consumer Advisory Board for the clinic.

In 2012, Chuck retired from full time social work and moved to the DC area. While in Boston he had been a volunteer at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in both the galleries and for the music program. Upon moving he sought out volunteer opportunities where he could utilize his interest in the arts and music. During one of his trips to The Phillips Collection, he stumbled upon a familiar name: Myron Stout. “I was flooded with tenderness for the man and the convergence in our lives that brought us to be friends. Lots of wonderful memories,” Chuck recalls thinking, “Of course the Phillips would have a Myron Stout in their collection.”

Art has also played an important role in his personal contemplative practice. Upon moving to the DC area, he began working collaboratively with the Shalem Institute where he is one of the leaders of a pilgrimage to Assisi, called “In the Footsteps of St. Francis and St. Clare.”

Chuck has been an Art Information and Phillips Music volunteer at the museum since 2013. He helps visitors navigate through the galleries and offers insights on the museum history and artworks. In addition, he is a music volunteer where he assists concertgoers during Sunday Concert performances. Chuck believes social work and art have similar and very important qualities—helping people understand themselves and the world around them. Both are creative endeavors which can lead to personal transformation.