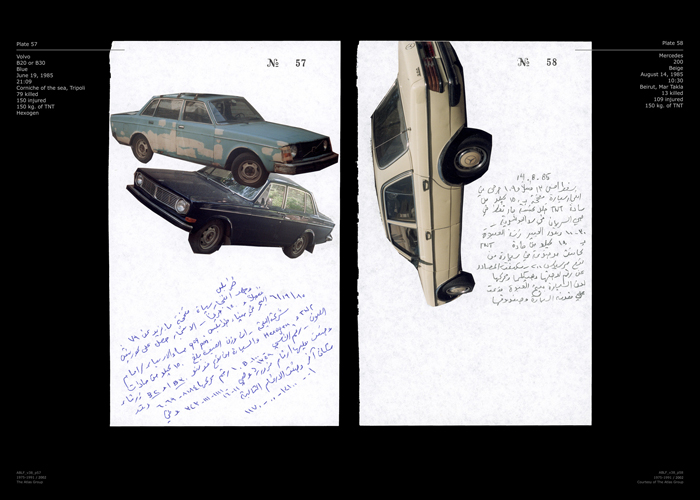

Walid Raad, “Notebook volume 38: Already been in a lake of fire,” 1991/2004. © Walid Raad. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

No photographs. No camera recording. A room of 75 people sitting in the dark listening to a man tell a story. Given the nature of the program – a Conversation with an artist – you trust what you hear is the truth. But that’s not Walid Raad’s style. What is fictional and what is factual weave together so intricately that, frankly, you’re left a little confused. Inspired, but confused. You realize you haven’t experienced a conversation per se, you’ve witnessed a performance.

All of us know that philosophical riddle about the tree falling in a forest with no one around and the question of whether or not it makes a sound. That’s what I keep returning to when I think of Walid’s stories – whether communicated in spoken word or implicit through his work. The investigation of what constitutes our reality – what is the truth – and the exploration of how we observe and react to our world is at the center of his practice.

Now, let’s not forget that we run the risk of assumption. What we tend to perceive as factual reality can turn out to be a constructed, fictional one (and vice versa). Of course, the lines can be blurred. What is fictional and what is factual can run so closely parallel to one another, or weave through each other, that your understanding of what comprises (your) reality is challenged (again and again). Moreover, our realities – I think we can venture here to use the plural – can exist with both irrefutably real and deliberately fabricated elements, often confused one for the other (as a resident of the nation’s capital with policy makers and international figures, I can think of a few examples). It’s the disillusionment that happens after the moment of realizing the truth that Walid does not concertedly, I think, try to avoid.

When it comes to political investigations – in art or otherwise – I’m inclined to say it’s difficult to determine our precise factual reality unless we can invest enough of ourselves to get close enough to understand the entire story, to recognize these irrefutable truths. Walid Raad does precisely this in much of his work with the project, The Atlas Group. Since the late 1990s when the project began, he has dedicated himself extensively to gathering as much information as he can about the contemporary history of Lebanon. Everything produced and collected is organized in an archive, in an effort to document the facts (or create proof, evidence to the truth). One of the areas of this project that I found most compelling was Walid’s effort to document every type of vehicle used in car bombings during the civil war in Lebanon from 1975 to 1991. He produced a book of 145 cut-out photographs of cars, corresponding to the exact make, model, and color of every vehicle used in car bombings during the near two-decade span of conflict in Lebanon.

I have to pause for a moment and be truthful with you (no deliberate fabrications I assure you; just hints of confusion). I was hoping I could avoid speaking about the philosophical references Walid pointed out – due in large part to the fact that I still don’t quite understand them – but in order to support my response to his conversation/performance I feel that I must at least try and explain. Jalal Toufic‘s declination of tradition explains that that which has been affected has essentially been or will be withdrawn, and in such has served a sense of resurrection of itself. This has greater clarity for me if I think about what Walid was saying in regard to those who have been deeply affected by an action or event – most noticeably in cases of violence and loss (such as the Lebanese civil war). To take this further: when you experience the loss of a loved one, you notice a sense of “nothingness,” some might say they “feel nothing.” You are numb, withdrawn from the reality of the act. Your ability to emote is negated by the intensity of the action itself – the loss of a loved one, violence, crime, so forth. This condition translates with our experience of something positive, provided the experience is profound enough to hinder our ability to articulate a response. If we marvel at something extraordinary in nature, if we’re brought to tears during a musical or theatrical performance, if we are left in such an acute contemplative state in the Rothko Room, we may have a tendency to explain our experience with “I was speechless.” It’s the same idea, I think, as Toufic’s declination of tradition, withdrawal, and resurrection.

Walid discovered that victims of the Lebanese conflict would often say “I feel nothing” in response to photographs and reports of the tragedies. In fact many would claim that Walid, who described to them his research, “saw nothing; understood nothing.” Walid has never shown his Atlas Group work in Lebanon. This is probably out of respect, but I wonder if it is also because he feels that the reception of his collected facts will be entirely withdrawn and negated of a comprehensible response.

Returning to this exercise of trying to distinguish irrefutable truth from deliberate falsehood, I think we can agree that it is the core of our existence. As human beings we are innately curious. We search for meaning, for truth. However, we have to be cautious of those with a subjective reality (one man’s fact is another man’s fiction). Walid alluded to this in his stories of encounters with Lebanese civilians, with executives of questionable investment firms, and with his research and speculation on the intentions of those behind the Saadiyat Project in Abu Dhabi. This investigation of fact versus fiction, what constitutes our reality, and the overall search for meaning happens every day. It’s essentially part of the human condition. A most recent example is the investigation of the reader’s experience in Greg Mortenson’s Three Cups of Tea. Up until the 60 minutes exposé that aired on Sunday, readers and followers of Mortenson may have sincerely believed his philanthropic effort to provide schools for impoverished children and may have been captivated by his dangerous encounters with the Taliban. Investigation seems to lead us to the contrary, that his stories of benevolence and danger are essentially Mortenson’s own version of the truth, his own subjective reality (apparently these schools are empty warehouses, and Mortenson’s brush with the enemy was really an encounter with tour guides).

One of the most interesting part of Walid’s work for me is the feeling of the unknown. I cannot always distinguish fact from fiction during his conversations. I have accepted this, though, as part of his performances. Walid suspends us in the unknown to keep us guessing. Keep us intrigued. Confused, but intrigued.

I can’t help but leave you with a line from one of my favorite movies. Diane Keaton’s character Erica in the Nancy Meyers film Something’s Gotta Give responds to Harry (played by Jack Nicholson) while arguing over his misleading behavior (deliberate fabrications masquerading as irrefutable fact) and hilarious defensive line, “I’ve always told you some version of the truth.” Erica comes back with: “the truth doesn’t have versions.”

Megan Clark, Manager of Center Initiatives

Pingback: The Results of our Experiment « The Experiment Station

Pingback: In February, the Conversation Continues « The Experiment Station