An interview between Meg Clark, program coordinator at the Phillips’s Center for the Study of Modern Art, and Klaus Ottmann, director of the Center and Phillips curator at large, on his installation in the Main Gallery of works from the permanent collection

Meg Clark: Was this your first time curating an entire gallery space from the permanent collection for the museum? What made you choose the Main Gallery?

Klaus Ottmann: An entire gallery space, yes. I think this is a kind of departure for the museum, in an effort to create more diversity and curatorial voices as far as permanent collection installations are concerned. The reason it is in the Main Gallery is because it was the first space available; it needed to be reinstalled after the Snapshot show, and I was asked to do it. I also think the Main Gallery is a beautiful space, because it really is a very traditional art gallery space. It has no windows, beautiful light, and is elevated to a certain extent–the viewpoint upon entering the gallery from the house is so interesting.

Some of the works here have elements of chaos, and collapse – which is something I think art is very much about.

MC: Tell us about your curatorial process, generally speaking and for this particular installation. Do you ever approach a project with a theme in mind, and, if so, what did you have in mind for this space?

KO: I have what you might call a non-traditional curatorial practice. It is less art historical and more influenced or informed by my philosophical background. I consider my practice to be one of structuralism, which is a form of formalism–one that considers form as content. I tend to have an a-historical approach, something that is very suitable to this museum since we do not have separate departments for different time periods, different media, etc. Years ago in other museums it was almost impossible to mix things between media and between different periods in the way it is done here. More and more museums are doing that now, but the Phillips was doing this from the very beginning, never having restrictions. There is a great freedom in that.

I never come to an installation or an exhibition with a preconceived idea or theme. I let it evolve from the works themselves. I look at a number of works and see what appeals to me. I do know that for this space I wanted to have a mixture of painting, sculpture, and photography. I especially wanted to show works we have rarely exhibited. As I was browsing through our databases and seeing what we have, certain things came to mind. For instance I like the idea of chaos and works that evoke a sense of uncontrollable circumstances or feeling. Some of the works here have elements of chaos and collapse, which is something I think art is very much about.

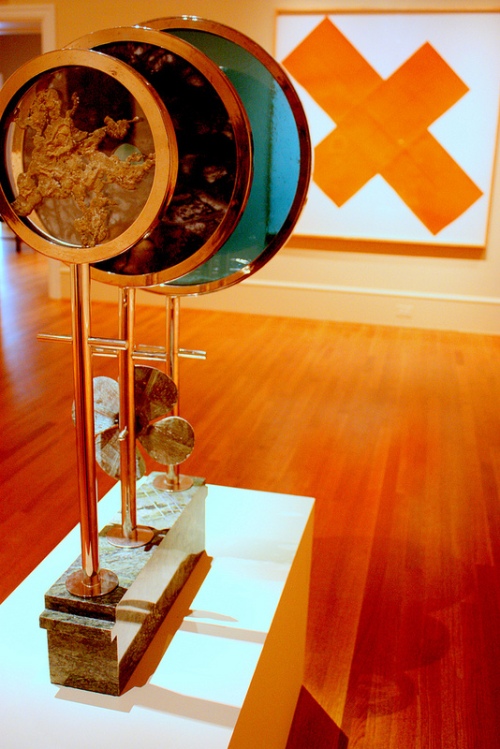

MC: In the center of the Main Gallery visitors will discover something they have not seen before, the sculpture by Morris Graves. In fact, many of us on staff were surprised, first of all, that this work is by Morris Graves, and second, that the Phillips owns this. Can you tell us more about it and why you chose it for this installation?

KO: It is apparently a weather station. I like it because it is very unusual, and it has a very interesting formalist quality to it. Also, weather has a lot to do with chaos.

MC: It is definitely unusual. Fascinating, but unusual. I noticed it is dated “1962/1999”–what does that mean?

KO: It means that it was originally done in 1962, but then some work was done later, and those changes were completed in 1999.

MC: It was gifted to the museum in 2001. Has it been shown before?

KO: It may have been shown briefly in 2001 when first given to the museum, but to my knowledge it has not been shown since. So this is pretty much the first time this work has been on view for an extended period of time since it was gifted to the museum.

MC: You mentioned that you do not approach a project with a particular theme. However the works here in the Main Gallery certainly have affinities–among the Georges Braque painting, Morris Graves sculpture, and Fairfield Porter works; the Anthony Caro sculpture, Brett Weston print, and Catherine Murphy painting; and certainly between the Robert Courtright and William Christenberry. Can you elaborate?

Nicolas de Stael, Birds in Flight, 1951. Felt-tipped pen on paper, 28 1/4 x 20 1/4 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1964.

KO: Some of the works that I picked are works that I am fond of like the Georges Braque, one of my favorites in the collection that I have seen hanging in the Music Room for a long time. I also picked some things that are very rarely (or never) out like the Morris Graves and Fairfield Porter works. I did a Fairfield Porter show at the Parrish Art Museum before I came here, so I was keen on seeing those. With the winter scenes in Porter’s works, rain in the Braque painting, and the Morris Graves sculpture being a weather station, the weather affinity is there. Weather, again, fits into this idea of chaos. And then there is this phenomenal Nicholas de Stael, which I find incredibly contemporary; it is an image of a flight of birds, which again, has that element of order within chaos.

So although I do not lock myself into any particular theme that is not to say affinities and relationships among the works will not result. It is partially following the works, partially intuition, partially my preferences that created this installation. I also made it a point to choose both better known artists and, to me, lesser known artists. Like, for example, Robert Courtright, who was unknown to me before I saw the piece, which I really like a lot. Then of course I saw this photograph by William Christenberry and recognized a formal relationship between the two. I do not always see these things clearly until they are out on the wall. I discover affinities and relationships through looking at works together that were not yet clear to me when I made the decision to hang them–which is, to me, the magic of doing art installations.

MC: So do you find yourself changing your mind a lot when installing a space?

KO: No. I move things around, but in terms of the works it is pretty clear what I want. I made a pre-selection online, on our database, and went into storage to take a look at them. I found some things in storage that I had not even come across in our database, like the Mangold work and the Siskind photograph. Once it was all in the space there were maybe two or three works I had pulled out that ended up not being hung because it was too much. But it all evolved very quickly. As I said, it is important to me that it is not a thoroughly researched and thought out process; it is an intuitive process. I let the art do the job for me. That way, I end up coming back and discovering things that I was not aware of when I made the decision to install it, which is really great. People may assume I was, but I am not always completely aware of elements that come through in an installation. That is the beauty of it. And I do not think it is supposed to be about me, although it does bring in a very personal perspective since I worked on it independently. My curatorial perspective is to let the works speak for themselves. And I think I have succeeded in that very well here.

MC: I’ve worked with you long enough now to understand that you like to think outside of the box, or the white cube as they say. The act of slowing down to experience something profound, or otherwise, with a work of art seems important to you. So important, in fact, that we organized a program in 2011 centered around the art of looking. The works on the walls here in the Main Gallery are not hung in perfect symmetry. A weathervane in the middle of the space beckons the visitor to walk around and examine it. The other two sculptures, I think, intrude a bit into the visitor’s space which, again, encourages the visitor to take a closer look, slow down, and really experience the works. How much of your emphasis on experience over interpretation played into your curatorial process for this space?

KO: I tried to limit the installation to more recent works from the 20th century, particularly postwar, but not exclusively (the Tack is a little earlier). But other than that I have no difficulties putting together works that have nothing in common with each other, art historically or otherwise, because I think they make an interesting dialogue. As I said, I prefer to let the works speak for themselves. I welcome the opportunity to mix media, and incorporating sculpture into this space was important to me. The placement of the Calder, Graves, and Caro sculptures create a diagonal dynamic that bring the rest of the works together and provides a connection between the walls. I think that is successful.

Sometimes I do not always see these things clearly until they are out on the wall. I discover affinities and relationships through works that were not clear to me when I made the decision to hang them–which is, to me, the magic of doing art installations. It is an intuitive process. I let the art do the job for me. . . . People may assume that I was aware of [these relationships], but I am not always completely aware . . . that is the beauty of it. I prefer to let the works speak for themselves.

MC: Did you learn something new that you did not expect when selecting the works?

KO: Well, speaking of sculpture, I was surprised by the number of reports of people stepping too close. This forced us to put pedestals under the Calder and the Caro, which is a pity. They are not supposed to or meant to have pedestals. Even though the pedestals are flat, they interfere with the works. However, this is something you have to do in museum practice, you have to compromise. The pedestals seem to have helped our visitors navigate the works. We certainly do not want people to get hurt, so we have a responsibility. Of course this whole thing reminds me of that famous saying: “Sculpture is what you bump into when you are trying to look at a painting.”

While I feel you should pay as much respect to the works of art and to the artists as you can, sometimes there are situations where you have to make compromises, for various reasons–to protect the work of art, to protect the visitor, etc. If you are a collector in your home or an artist in your studio, you can do whatever you want. But if you are in a museum, in a public space, you sometimes have to make these compromises. That is what it means to work in a public institution.

(left to right) Morris Graves, Weather Prediction Instruments for Meteorologists, 1962/1999. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.; Robert Mangold, X Within X Orange, 1981. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Photo: Kate Boone

MC: Well, I think the space definitely invites the viewer to slow down and look, learn something new, and have an experience. Do you have a favorite piece in the installation?

KO: The Morris Graves. It is so surprising. I saw a picture of it, but it was hard to figure out what I was looking at because it had to be assembled, so it was not until it was actually on the pedestal and we put all the pieces together that it really came together for me. It is really a fascinating piece and by far my favorite. I hope visitors will enjoy the dynamic between the Mangold and the Graves, noticed especially as you ascend the stairs from the house to the Main Gallery– you see parts of the Mangold through the semi-transparent, blue-tinted glass of the Graves sculpture. In many ways this relationship is a great introduction to the space.

Megan Clark, Manager of Center Initiatives