Sherman Fairchild Fellow Ariana Kaye on the personal history revealed in Ricky Maynard’s portrait of Gladys Wik Elder

In my previous blog post, I discussed how photographer John Edmonds transforms traditionally objectified representations of Black people into more empowering and realistic representations. Indigenous peoples have also historically suffered the indignity of objectification. Here, with Ricky Maynard’s photograph of Gladys Wik Elder, we have an example of a powerful memorial to an Indigenous person, Gladys Tybingoompa (1946-2006), who spent her life fighting for equal land ownership for the Wik people in Cape York Queensland, Australia.

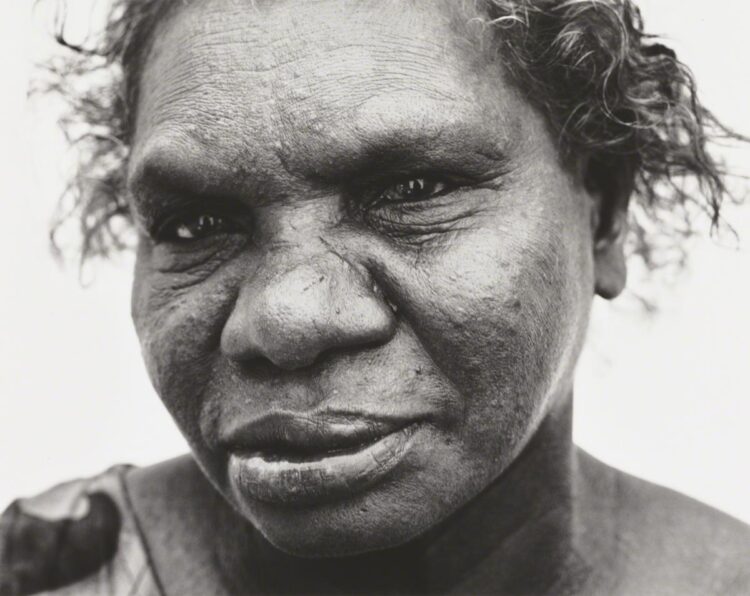

Ricky Maynard, Gladys Wik Elder (from Returning to Places That Name Us), 2000, Pigment print on paper, 12 x 16 in., The Phillips Collection, Museum Acquisition, 2017

This photographic portrait was acquired by The Phillips Collection as part of an effort to present a more diverse, inclusive, and globalized perspective of photography. Photography is an important aspect of the collection, originating with Duncan Phillips’s relationship with Alfred Stieglitz. Phillips said Stieglitz had mastered the medium and inspired the museum to continue to expand its photography collection over the years.

Ricky Maynard, an Indigenous Tasmanian artist, created the photographic series Returning to Places that Name Us in 2000. This portrait of Gladys is one of five Wik Elders portraits that Maynard created for the series to bring attention to the Wik Decision—not just as a matter of current concern, but something that held broader importance for the entire country and its colonial history. The Wik struggle became known as the Wik Decision, or Wik Peoples v. Queensland of 1996, in which the High Court of Australia determined that people who were leasing pastoral land from the government were not the exclusive owners of that land. The court held that the same land also belonged to the Indigenous population. That was a great achievement. However, it was short lived, and soon the Native Title Act, which had given Indigenous populations ownership of land, was modified in favor of government owners and leasers of land. This made it more difficult for Indigenous people to claim land ownership.

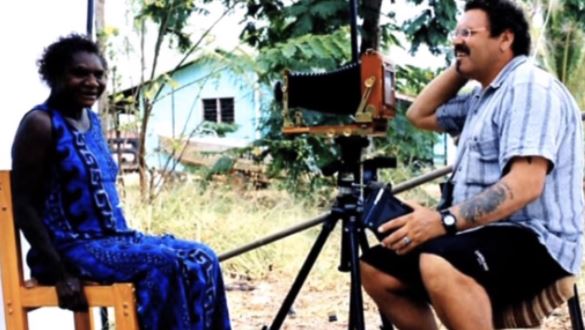

Still from a video by the Art Gallery of New South Wales showing Gladys Tybingoompa sitting for her portrait

Gladys sat for her portrait in Maynard’s backyard. The portrait shows a close-up view of Gladys, emphasizing heightened emotion in her expression. Viewers can even see her crack a smile as she poses for the camera. This smile evokes her full-of-life personality; Gladys famously danced outside of the Australian High Court on the day the court handed down its decision that Indigenous communities should have jurisdiction over their own land. Maynard said this series transformed his photographic practice, stating: “I saw every picture. I looked into the faces of all those Aboriginal people and it was sad. I started questioning the photographer’s role. It changed my life and the way I viewed pictures.”

Curator Hetti Perkins from the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Australia describes how the texture of Gladys’s face reflects her peoples’ history and their perseverance on the quest for equality. To me, the complex topography of the Wik people’s land becomes visible to the viewer precisely because of Maynard’s proximity to her facial features. As discussed by Perkins and captured by Maynard, Gladys’s face provides us with a map of the privations, confiscations, and battles fought on this journey. By highlighting the geographical topography on Gladys’s face, the photograph reveals the indistinguishable connection between Gladys and her ancestral land.

This portrait of Gladys Tybingoompa teaches us how much we can learn about a person and their history from a close-up portrait. If you were to get your portrait taken, what would you want people to know about you?

For more information:

- Video about Gladys Tybingoompa and photographer Ricky Maynard: https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/channel/clip/536/

- O’Connor, Pamela. “The “Wik” Decision: Judicial Activism or Conventional Ruling?” Agenda: A Journal of Policy Analysis and Reform 4, no. 2 (1997): 217-23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43198890.

- Durmush, Georgia. “Explainer: Wik vs. Queensland” SBS, 8 July 2018 https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/explainer/explainer-wik-vs-queensland

Thank you for posting this story. The portrait of Gladys Tybingoompa and of the Wik people are deeply moving. For me they epitomize the plight of many people around the world, including that of First Nations people in the United States whose land has been taken away and who are by and large left out of today’s discussions on equality, social justice, diversity, and inclusion.