David Driskell: Icons of Nature and History is on view through January 9, 2022.

David Driskell often stated that “art is a priestly calling,” and his artistry has deep roots in his Christian spiritual practice. Son of a Baptist minister, Driskell was informed by his father’s sermons as well as his own experiences in the Congregational church for more than 40 years. Biblical themes have been a consistent source of inspiration from the 1950s forward. Inspired by his father’s sketches of angels, they become a frequent theme in works such as Gabriel (1965) and Let the Church Roll On (1995–96). Driskell’s abiding interest in Byzantine art is reflected in the flatness and frontal posture of figures that recall sacred Christian icons.

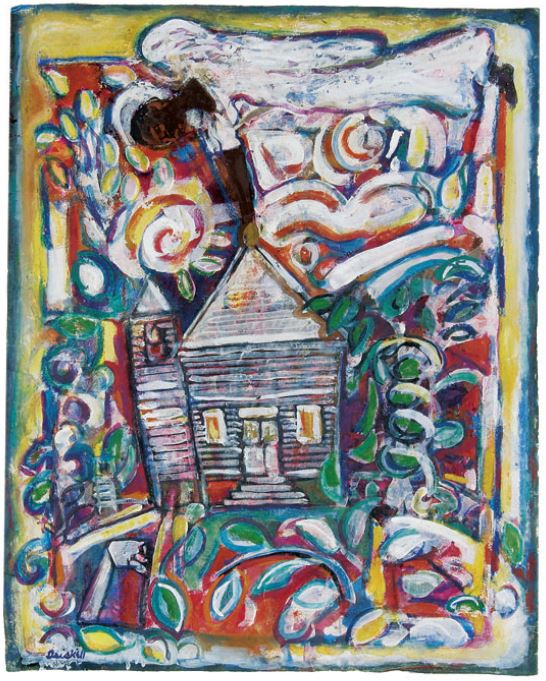

David Driskell, Let the Church Roll On, 1995–96, Encaustic, gouache, and crayon on paper, 24 1⁄16 × 19 1⁄16 in., Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine, Museum Purchase, Lloyd O. and Marjorie Strong Coulter Fund, 1998.23 © Estate of David C. Driskell

In 1994, Driskell began a series of works that featured a small chapel with a protective, hovering angel. Titled after the popular spiritual “Let the Church Roll On,” this work conjures memories of the church from Driskell’s past, from his father’s interest in drawing angels, to Hunt’s Chapel where Driskell was baptized, and more broadly to the deep-rooted and enduring ministry of the Black church. Driskell surrounds the wood-framed chapel with verdant greenery, suggesting perhaps that nature, like the church, will continue to roll on.

David Driskell, Black Crucifixion, 1964, Oil on cotton canvas, 57 × 30 1⁄4 in., Collection of Larry D. and Brenda T. Thompson, Atlanta © Estate of David C. Driskell. Photograph by Gregory R. Staley

Completed the year the Civil Rights Act was signed into law, Black Crucifixion signifies the persecution and suffering of Black people in America. Its critique is social. The figure looks out directly, if probingly, as an eternal witness to prevailing systems of racial violence, segregation, and discrimination. Driskell’s depiction of the body seems forensic, like an X-ray, and recalls his 1956 homage to Emmett Till, Behold Thy Son (1956). The application of planes of color, like stained glass, draws upon Driskell’s study of Analytical Cubism and his admiration for the art of Georges Rouault.

Join us on December 14 for a conversation with collectors Larry and Brenda Thompson, who were close friends with David Driskell and collected his work.