All of the concerts of our 80th season of Phillips Music are being presented online. In the second of this two part series, Director of Music Jeremy Ney shares insights on how the performing arts world has adapted to virtual concerts. Real Part I here

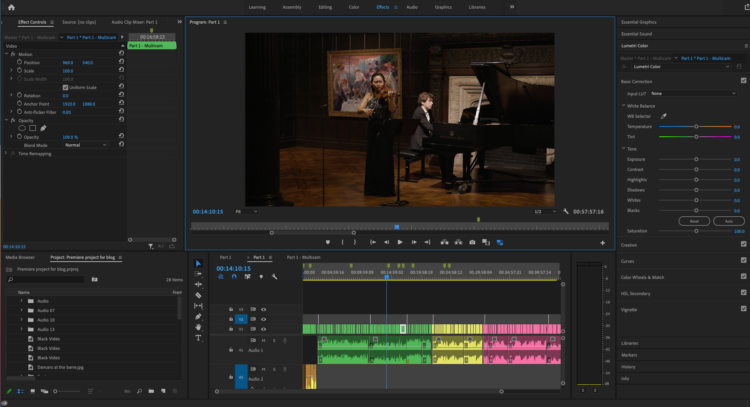

Timo Andres and Rachel Lee Priday performing in Andres’s home. Register for the broadcast on March 7!

How has the concert world adapted to the digital space?

2020 saw many musicians and artists turning to the digital space to present their work. This ranged from professional recordings in empty concert halls to home-spun DIY recordings using basic equipment. Some artists, like pianist Igor Levit, built a huge following for his daily house concerts, which offered comfort and respite from worldwide lockdowns in 2020. Other artists, like pianist Timo Andres (who appears on our series on March 7), replaced cancelled career-defining moments (Andres was set to give his Carnegie Hall solo recital in 2020) with virtual realizations that offered an intimate portrait of creative adaption. The overarching message in the performing arts seemed to be: don’t let the circumstances defeat you, find ways in which such restrictions can hold generative potential to do something new.

How do your musicians feel about performing virtually?

Well, it clearly does not replicate the experience of performing for an audience. Audiences are the lifeblood of performances; performers thrive off their presence, their enjoyment, their love of the music being played. There’s a reciprocal exchange that happens in the communion between artist and audience and so the absence is just that: an absence, something you miss and hope will return soon. We all long for the day when we can bring audiences back safely to enjoy the thrill and vitality of live performance.

All musicians are different though and some take to the virtual space with greater ease than others. Some musicians treat a virtual concert like the live experience, and if it is being pre-recorded (which is increasingly prevalent), then they do one take to preserve that freshness of the moment. However, others like to return to specific passages to repeat them and treat the experience more like a session in a recording studio. Both have their merits but are very different approaches. Regardless of which mode an artist adopts toward virtual performance, I think it is safe to say that everyone I’ve worked with hugely misses the energy that is created with a live audience.

Is there any advice you have for an audience member new to virtual performances?

My advice would be to try to invest the same degree of patience in a virtual performance as you would (or did) when we were all able to gather in-person. While the digital realm presents many possibilities, we know that that digital attention spans are notoriously short. There are obvious reasons for this: we live in a visual culture and the internet-age has flooded our lives with a constant stream of visual imagery. Saturation has demanded economy, and often the advice in social media circles is to keep video content to no more than 60 seconds, which doesn’t get you very far into a concert! So, I would urge a virtual performance audience member to look at the concert experience as something different to the bombardment of visual ephemera that we all experience every day, to look upon the experience as something to delve into, be captivated by, to lose yourself in. That’s what we strive to put into the world.