Artist Shiloah Symone Coley shares her experience interviewing Parklands resident Miss Lula and creating Mama Lula, an animation now on view at Phillips@THEARC about Miss Lula’s story.

Roses fill Miss Lula’s living room when you peer in through the street-facing window. It’s July 12, 2022, just over a week since her 89th birthday on July 4. The flowers transform her intimate living room into looking much more like the garden just outside her window.

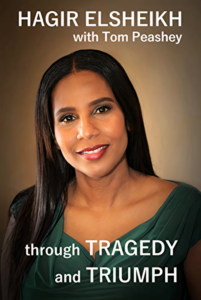

Miss Lula pictured just after her July 4th birthday. Photo: Shiloah Symone Coley

Her flowers thrive in the mid-summer heat and humidity. She wears a red, white, and blue Washington, DC Nationals baseball t-shirt with a matching hat that reads “LOVE.” It’s not the fourth of July anymore, but something feels quintessentially American in a different way–not just her outfit, but her, all 5 feet of a July 4th baby now in her elder years. She’s seen so many 4th of Julys.

I met Miss Lula earlier that year during the winter at one of the Creative Aging programs at Phillips@THEARC. An intimate program that day, Donna Jonte and I were joined by Miss Lula and her friend Miss Pam. We ate, talked, and made art. But one of the most memorable parts of that day were the stories Miss Lula told about the work. There was a story behind every piece. So when I had the idea to interview Black women who lived around THEARC in the Parklands community, she landed first on my list.

As I walked into THEARC with her for our first interview, people at the front desk and coming in and out of the building immediately knew who she was. Not only were pleasantries exchanged, but updates on life events were eagerly shared. She seemed to carry about her a unique mix of warmness and honesty that let people know it was okay to be themselves and say how they were really feeling with her. It helps that she’s lived in the community in the same apartment for 60 years. She’s watched some of these folks grow up.

As I interviewed Miss Lula, what I found most interesting about her story was her persistence to stay in the Parklands community. I think as a child I often dreamed of leaving home, moving, doing my own thing. Then, in my adulthood I have become accustomed to a semi-nomadic lifestyle where I move every couple of years. Both forced migration and chosen migration run rampant across all eras but seems particularly normalized with younger generations. On my block in Northwest DC my roommate and I have noted half the people who used to live on our block have moved within the past year. As we noticed how quickly and frequently the shift occurs, we began to wonder what it means for the community when people are able to stay.

Miss Lula knows migration well. She arrived in DC at Union Station as a little girl with her siblings after her maternal grandmother sent them up north from South Carolina to be reunited with their parents, an experience not uncommon to most children growing up during the Great Migration. She would spend the rest of her life in Maryland and DC, and most of her life in her current residence in Parklands. Mama Lula is about one woman who has been able to stay and has chosen to stay in her community despite the changing landscape around her.

I originally set out to tell a story about the community from various perspectives with insight from multiple women from different generations. And perhaps that project will still take shape one day. But it became clear after interviewing Miss Lula, that her voice was deserving of its own project. Maybe the countless cards and flowers she received on her birthday were indicative of not just the lives she’s touched, but the importance of her as an elder in the community with a life and story to share.