2021-22 Sherman Fairchild Fellow Shiloah Coley speaks with Inside Outside, Upside Down artist Desmond Beach, whose work #SayTheirNames2 has recently been acquired by the museum.

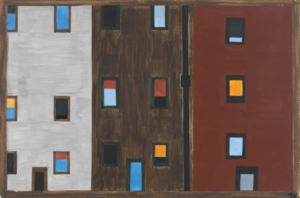

Desmond Beach, #SayTheirNames 2, Fabric and paper, Courtesy of the artist

Desmond Beach puts the past and present in conversation with each other, giving context to the times we live in through his collage series #SayTheirNames. “I often call myself an intercessor. I move between time and space, whether it’s the past or present or into the future,” said Beach.

He uses old newspapers, photos of enslaved people, and his own photographs to layer his collages, creating depth on top of the patterned fabric in the background. From afar, one might only see the silhouette of a man in #SayTheirNames 2, which was recently acquired by The Phillips Collection. But as you get closer, it becomes nearly impossible to determine how many black-and-white photos are layered into the central silhouette surrounded by a seemingly repeating image in a halo-like circle around the figure’s head.

Desmond Beach, Courtesy of the artist

Beach smiles as he says, “No pun intended, but it’s really layered, and I think that’s what it’s really about when I am trying to speak about history and present time. Collage, for me, allows for the physical layering and conceptual layering as well.”

As he dives into the past, he often finds himself combing through archives at places like the Library of Congress in unassuming rooms where it’s just him and stacks of images and materials to source from. “You go in and just start pulling through images, and for some reason that act feels like me connecting to the past. Like it gives me some threshold or entrance into the past that I wouldn’t have if I just started searching on the internet for images,” Beach says.

As he sifts through the archives he begins to imagine the setting and context behind a photo, asking himself—What might it have been like that day? What did it smell like? What were people saying? What was going on just outside of the shot of the photo? It’s these questions that connect his taking photos at Black Lives Matter protests to his mining images in the archives. The events aren’t only bridged, but the livelihoods of the subject are. What Black folks struggle for today is not something they struggle for alone, but something a seemingly never-ending lineage of people from the African continent have struggled for.

When asked about the emotional labor required to go through so many archives while also living in a media age where we’re bombarded by images of police brutality and Black suffering, Beach mentioned that sometimes he needs to turn off the news and unplug. But what really carries him through is knowing he’s not alone and being in a position to turn the pain into something beautiful.

From inside the artist’s new studio space in New York, Courtesy of the artist

“When I’m in my space working it feels like I’m not alone. I feel like they (the ancestors) are with me, like they’re right there behind me,” says Beach. “I feel like I was called to do it—to look at that pain, to tell it, and then to try to find a way to bring healing with it.”

This is a lesson Beach gleaned not only from the older ancestors, but the newer ones, too, as he reflects on the crucial role his maternal grandmother played in his upbringing in Baltimore, in a household where civil rights were constantly a topic of discussion. “My mother’s mother really instilled the idea of faith in us, and having this sense of—there’s something higher than you. I think about her everyday when I’m in the studio. I think that’s where my whole connection to the ancestors and my faith comes from, and all of that is why I try to be so intentional.”

While the traumas of the past run through the veins of our society, sometimes even in our own bodies, this trauma also offers an opportunity for collective healing. But in order to begin to heal, we’ve got “to bring voice to the pain,” as Beach says.