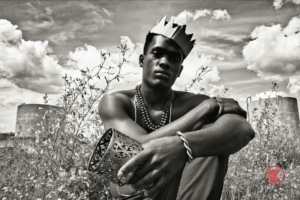

2021-22 Sherman Fairchild Fellow Shiloah Coley speaks with Inside Outside, Upside Down artist Aaron Maier-Carretero. The Phillips Collection is proud to announce the acquisition of his work, not in front of the kids.

Aaron Maier-Carretero, not in front of the kids, Oil on canvas, 55 x 72 in., Courtesy of the artist

In fifth grade, Aaron Maier-Carretero got in trouble at school. He got the punishment many of us are familiar with for minor offenses in the classroom—he wasn’t allowed to go to recess. But this time being stuck inside was a little different. One of the teachers egged him on to make a drawing and enter it into a contest in celebration of the upcoming fifth grade graduation. He didn’t think much of it. He spent his time inside drawing instead of basking in the sun with the other kids running on the playground that day. Later, he’d be named the winner of the school-wide competition.

Many of us start off approaching art with abandon as kids. We lose that sense of abandon as we get older, unwilling to be bold and more interested in pursuing a career with a steady income and dependable lifestyle. As Aaron navigated through his education, he found art still offered him something during his troublemaking years in high school. “It was an escape,” said Maier-Carretero. “It was something I was good at that I just liked doing because it was something people cared about and it gave me a sense of worth and acceptance, and I followed that.”

From inside the artist’s studio

Eventually, he rediscovered that sense of abandon, which led him to switch courses from following a pre-med track to pursuing his undergraduate degree in art at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Fast forward nearly a decade and his painting, not in front of the kids, was selected for Inside Outside, Upside Down. The piece has now been acquired for the permanent collection.

Aaron’s narrative paintings dance between realism and caricature in their representation of the human form and condition. “When I started becoming more loose and cartoonish, I was able to get more emotion out of the characters I was drawing, the people, and that gave me more substance.” As he read more about comics, he understood the power and impact reducing a form could have and the control it could offer. He could eliminate some things and focus on others, drawing the viewer’s attention to the core crux of a moment in the work. Being able to execute tight renderings and simplified cartoonish drawings offered him a new tool to be used decisively and intentionally in his work.

“I wanted to be very intentional about some things and I found that cartoons and caricatures are more expressive in that way sometimes,” said Maier-Carretero. “It just depends on what fits the mood better.” Maier-Carretero taps into his own family as a source of motivation, interrogating the occurrences of his upbringing, tapping into memories, journals, and photographs. He paints what he knows or what he thinks he knows or maybe what he hopes to know—himself and how he makes sense of the world.

From inside the artist’s studio

His work serves as a gateway into understanding and questioning the common human condition. Painting has become a means of processing for Maier-Carretero that ultimately results in a greater sense of self-acceptance for the artist. “I’m able to accept my own experience as part of a human experience whether it’s fortunate or unfortunate,” said Maier-Carretero. “I want to tell the story of what I don’t . . . of what I guess I don’t know what to do with. Like I don’t know what to do with these feelings of seeing people suffer, seeing myself suffer, seeing my family suffer.”