In 2019, Smithsonian American Art Museum conservator Gwen Manthey and researcher Sydney Nikolaus examined the Phillips’s work Breeze Rustling Through Fall Flowers by Alma Thomas. Read an excerpt from their report to learn about Thomas’s process and join us on January 13 for a talk with Gwen Manthey and Amber Kerr.

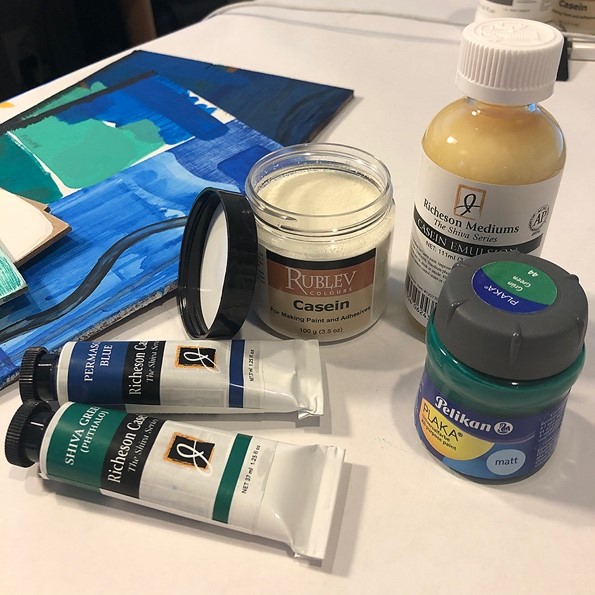

In 2019, the Smithsonian American Art Museum began analyzing 40 of Alma Thomas’s paintings, including works from its own collection, The Phillips Collection, the National Museum of Women in the Arts, and the National Gallery of Art. Research focused on the tools and techniques that Thomas employed throughout her career from the early 1950s to her death in 1978. Using a modified Nikon D810 digital multispectral imaging camera that captures images across the electromagnetic spectrum, conservators identified the art materials and determined the layering construction of Thomas’s paintings. On November 18, 2019, SAAM conservator Gwen Manthey and researcher Sydney Nikolaus examined Thomas’s acrylic painting Breeze Rustling Through Fall Flowers at The Phillips Collection.

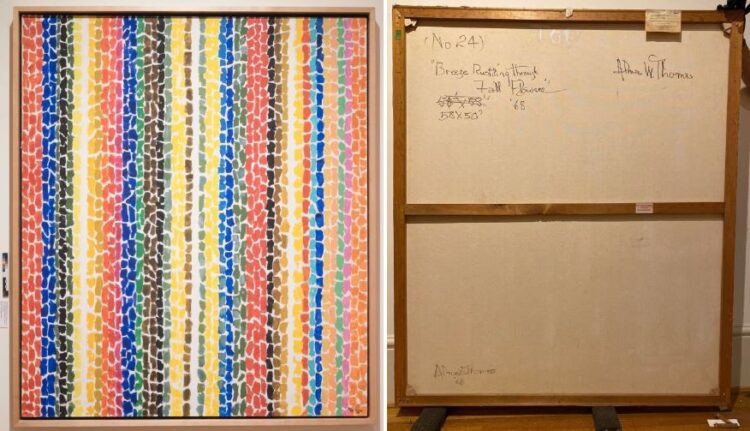

Figure 1 (left) Breeze Rustling Through Fall Flowers, normal light illumination, and 2 (right) verso.

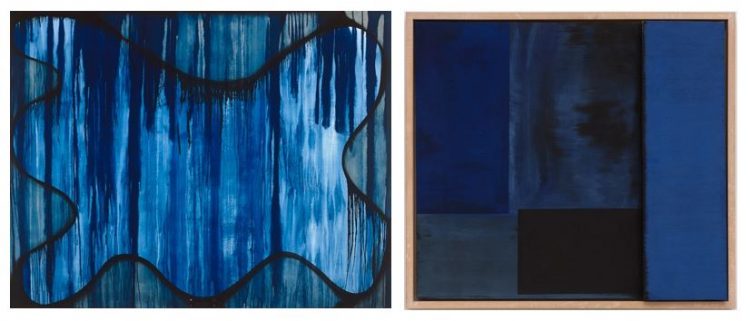

INFRARED REFLECTOGRAPHY (IRR)

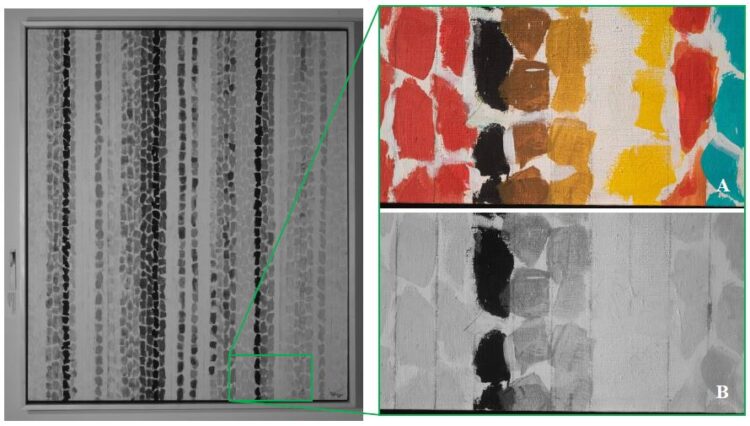

They gleaned new information using infrared reflectography (IRR), a process where infrared wavelengths penetrate paint layers and are absorbed by carbon-containing pigments and drawing media, and then reflected by underlayers of white ground and paint. They learned that Thomas defined each color row in Breeze Rustling Through Fall Flowers by drawing vertical lines with a sharp graphite pencil on the prepared canvas. The evenness of these lines (spaced 1 inch apart), guided by short tick marks, suggest the use of a straight edge ruler (Figure 3a-b). Thomas also made straight lines at the inner top, left, and right edges of the painting’s edge to indicate the perimeter of the composition.

Figure 3 (left) infrared reflectograph overall image. Details in normal light (A) and IR (B) show Thomas’s graphite pencil lines for each vertical row of color pats.

ULTRAVIOLET-INDUCED LUMINESCENCE

Using UVA-induced luminescence from a Labino UV Light, the conservators found a strong autofluorescence in the rich orange paint that Thomas applied in several of the orange rows seen in the top right corner of the painting. This provides more insight into how Thomas layered her paint pats in each row (Figure 5).

Figure 4 (left), detail of top-right corner in normal light and 5 (right) in UVA-induced luminescence. The strong autofluorescence of the orange paint reveals how Thomas layered several of her rows.

SUPPORT – CANVAS AND STRETCHER

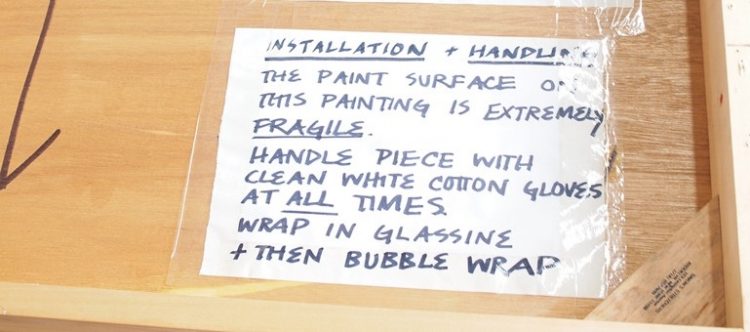

Thomas chose a basket-weave medium weight fabric with an average thread count of 36 x 32 threads/inch for her canvas; it is attached to the stretcher with staples (Figure 6). The stretcher consists of four wooden stretcher bars, with mitered slot and tenon joints, and a horizontal crossbar. Impressed stamps (Anco bilt, Glendale, N.Y. and Grumbacher Artists’ Materials, New York) shown in Figure 7, were found on the stretcher bars. Each join contains a pattern of four large holes (Figure 7), possibly the location of previous metal plates added by the artist to increase the strength of the support; they have since been replaced by keys fixed with cord and screws. The painting’s verso contains several inscriptions by the artist in a black felt-tipped marker, her signature, the title, date, and dimensions of the work (Figure 2). The artist wrote “TOP” in a white paint or acrylic primer.

Figure 6 (left), detail of top-right corner tacking edge and 7 (right) of the same corner shown on the verso.

PAINT

The painting is comprised of vertical rows of colorful acrylic paint, applied by brush, on top of the white ground. Examination of the painting’s edges show that the ground was applied by the artist. The ground has seeped through the canvas in some areas of the verso (Figure 7). Thomas applied additional layers of paint to several of her color rows. Often, they match the initial color, but there are instances where Thomas layered a different color such as blue gray over green and blue paint pats. The paint pats are formed from multiple brushstrokes, measuring about an inch wide. Thomas used a thinner brush to reinforce the white spacing between the pats with white paint. There are many downward drips of paint located between the yellow rows (Figure 8) and in the nearby orange row (Figure 9). The downward paint drips shown in Figures 8-9 indicate that Thomas did not work flat and that she watered-down her acrylic paints.

Figure 8 (left), detail of downward paint drips in the yellow center rows and 9 (right) in the orange center row.

To learn more about Thomas’s process, join us for a conversation with Gwen Manthey and conservator Amber Kerr on Janaury 13 at the Phillips about their research.