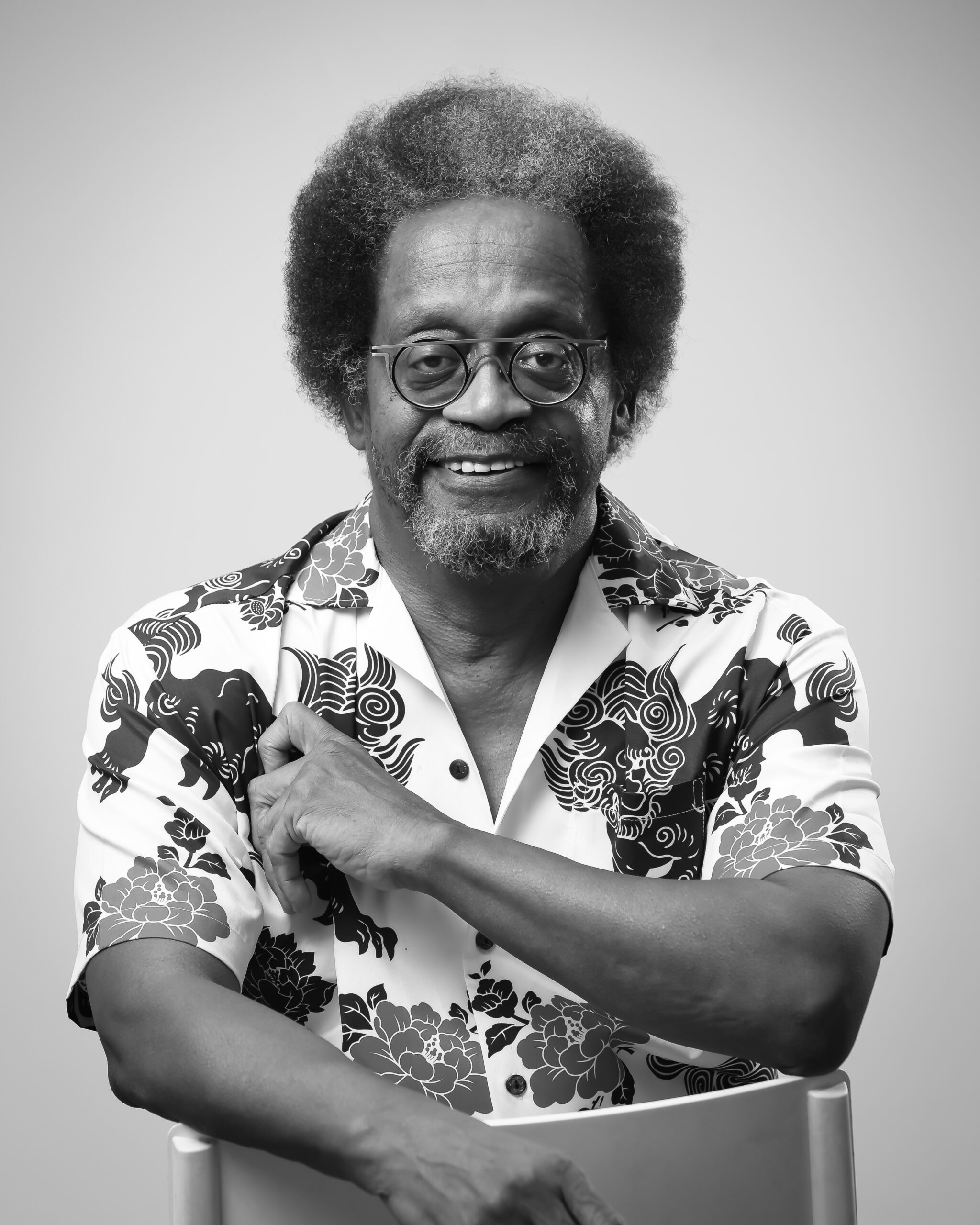

Marketing and Communication Detail Summer Roshni Bhullar reflects on her favorite artist in the collection.

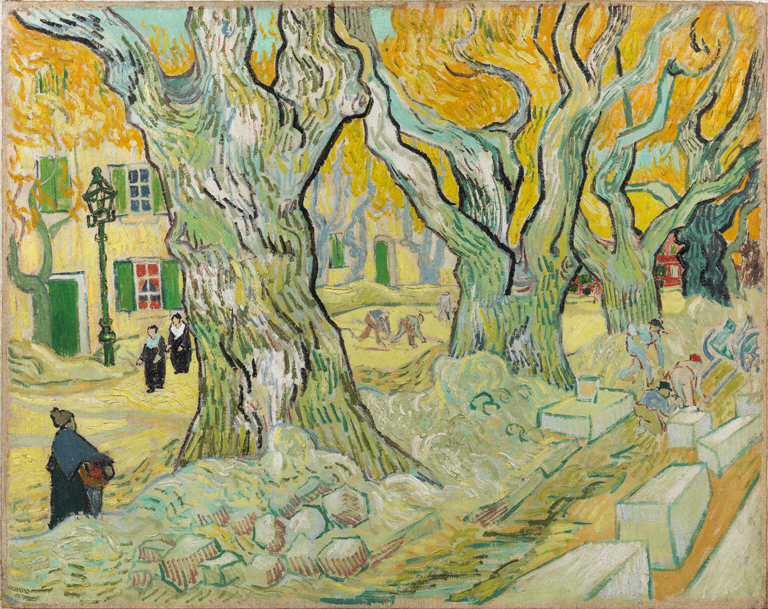

I would like us to take a walk in Vincent van Gogh’s shoes and try to see the world through his eyes for a few brief moments. Imagine you are Van Gogh—the artist, son, brother, lover, genius, and so much more. Now picture being in a mental asylum, thought of by everybody—including yourself—as being mentally unstable. How would it make you feel?

Yellow is the most visible color of the spectrum. It is cheerful, alive, vibrant—it depicts light and, most importantly, our sun. The love of sunflowers is a desire to capture the warmth and light of the sun. As artist Wassily Kandinsky said, “Color is a power which directly influences the soul.” Yellow wakes up the brain and is associated with feelings deeper than happiness. So why would someone be obsessed with sunflowers? Yes, they are bright and beautiful, but there seems to be something deeper than the aesthetics of this flower that drew Van Gogh to paint them repeatedly.

Vincent van Gogh, The Road Menders, 1889. Oil on canvas, 29 x 36 1/2 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1949.

Before he was born, his parents had a stillborn who was to be named Vincent. Hence, he started his journey feeling like a replacement, like a shadow of the eldest child that could have been. Before he became an artist, Van Gogh lived in many different cities and did many jobs. He decided to become an artist in the last decade of his life and his nomadic lifestyle continued. He had a Christian upbringing and also tried to become a preacher. His beliefs evolved throughout his life.

He was on a constant quest for something, in search of answers to his questions. He tried to answer his questions through religion, through his travels, through relationships, and through his art. But he always came up short. He left religion, relationships never worked, and art never gave him success. The one person he had the strongest and the closest bond with was his brother, Theo. Even though his brother loved him and was his biggest supporter and confidant, Vincent was still left wanting for more in life. Maybe his “more” was his unanswered questions, a cure for his loneliness, or success in his art. Or maybe his “more” was a desire to be understood.

Vincent Van Gogh, Sunflowers, 1889, Oil on canvas, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

When we look at his artistic career and all the art he has created, we can see his genius reflected in it. He wrote hundreds of letters during his life and was also good with words. Yet he felt something was missing. Throughout history many famous people have been posthumously understood and given recognition. What about those moments of painting and creativity, which they spend alone? What must go on in their heart and mind? Isn’t it human nature to want to share? Isn’t it human nature to want to be understood?

As the body needs food, the genius needs and wants to be understood. Throughout his life, we see a constant search for it and a constant lack of being fulfilled. Because of this—because his mind was not nourished with understanding—he started to doubt himself, to question his own sanity. Imagine someone born with a special genius ability trying to articulate their world. The first step would be acceptance of the genius from the person themselves and then others. As an artist who tries to articulate with words and colors, I feel that Vincent Van Gogh was a misunderstood genius labeled as mentally ill. His circumstances led him to break down.

His love for sunflowers showed his search for light within and without. He could not find what he was searching for, and eventually gave up his quest for light.