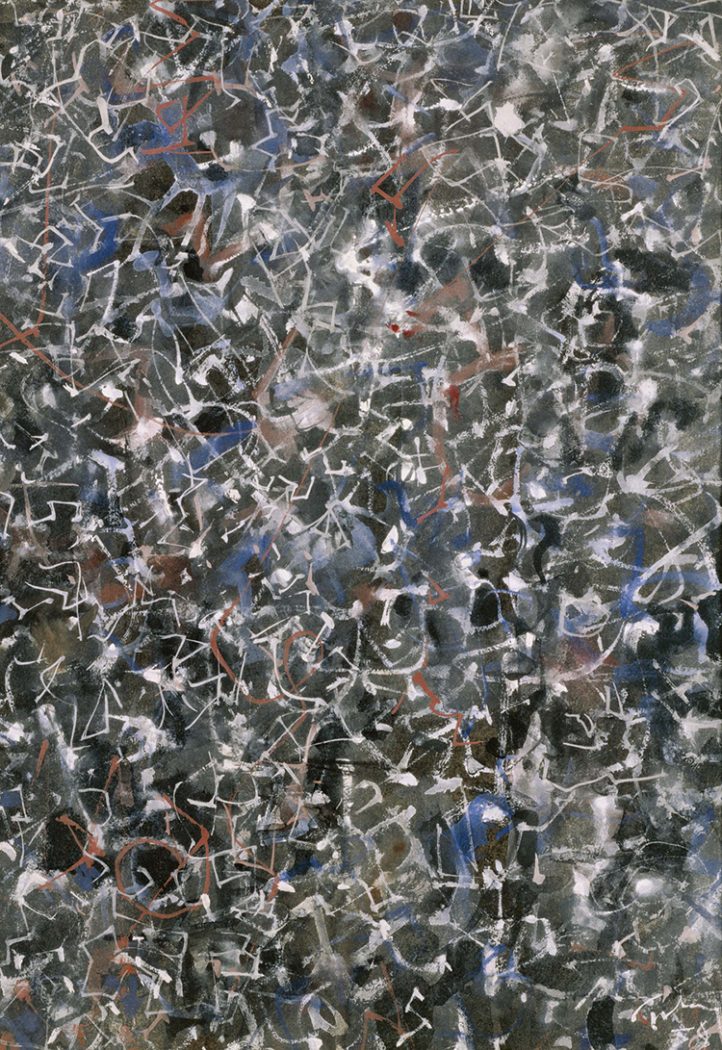

Adolph Gottlieb, The Seer, 1950. Oil on canvas, 59 3/4 x 71 5/8 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1952. © Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

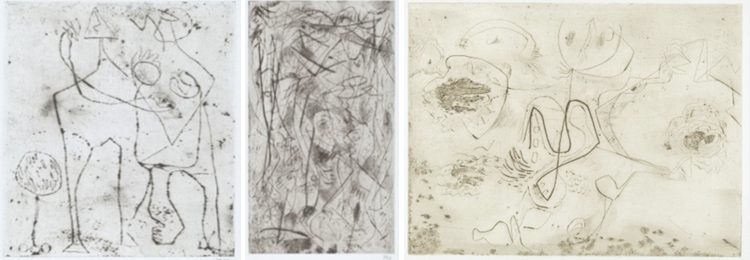

In 1941, in the aftermath of Paul Klee’s death and memorial retrospective organized by the Museum of Modern Art, Adolph Gottlieb produced a new, daring series, which eventually included over 500 works. He called these abstract inventions pictographs, or paintings filled with hieroglyphic-like forms. The Seer is one of the largest and last in the series. In a flat grid, Gottlieb juxtaposed abstract symbols conjured through free association with universal archetypes such as the arrow, circle, triangle, and ellipse in a manner reminiscent of Klee’s mature compositions.

During the 1940s, Gottlieb drew on Klee’s example in creating a unique artistic language that reconciled several opposing elements: line versus color, structure versus spontaneity, thought versus feeling, and stasis versus dynamism. According to Klee, these dualities mirror the primal conflict that has existed since the beginning of human existence. Gottlieb echoed the view, noting, “These opposites parallel our inner conflicts which are usually unresolved.”

This work is on view in Ten Americans: After Paul Klee through May 6, 2018.