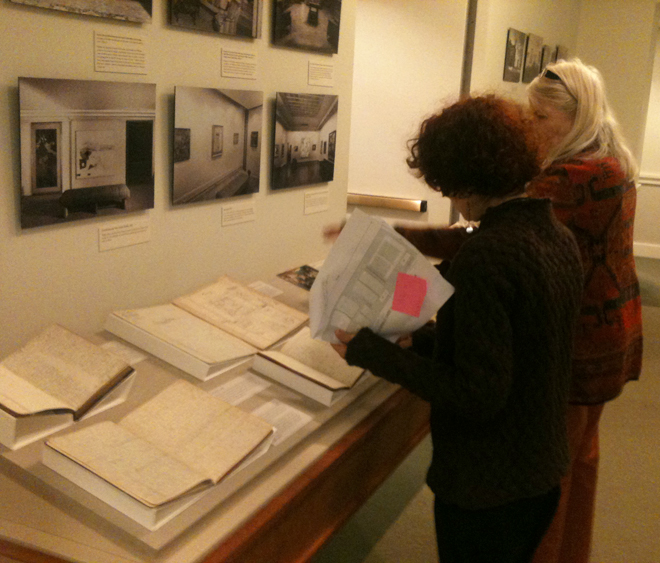

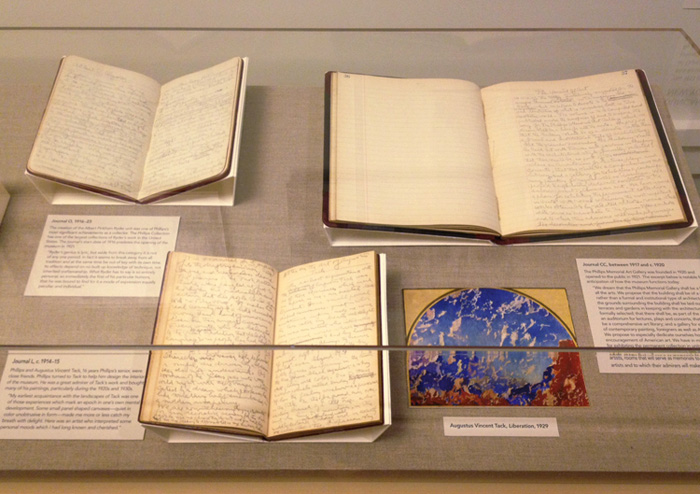

Caption: Duncan Phillips’s journal from between 1917 and c. 1920, on view in the Reading Room through February 2015. Photo: Vivian Djen

Duncan Phillips was a prolific writer. Starting in his days as a student at Yale, Phillips wrote about art and literature, recounted trips abroad, and recorded his dreams for his museum. Meticulously cared for in the Phillips archives, the texts from the 1900s to 1930s show the development of his collecting vision and his passion for art.

Phillips’s journals from 1917 to 1920 anticipate the museum’s opening in 1921:

We dream that the Phillips Memorial Gallery shall be a home for all the arts. We propose that the building shall be of a domestic rather than a formal and institutional type of architecture; that the grounds surrounding the building shall be laid out with terraces and gardens in keeping with the architectural style formally selected, that there shall be, as part of the scheme an Auditorium for lectures, plays and concerts; that there shall be a comprehensive art library; and a gallery for exhibitions of contemporary painting, foreigners as well as American. We propose to especially dedicate ourselves however to the encouragement of American art. We have in mind a plan for exhibiting the permanent collection in units with rooms containing the most important works obtainable by selected artists, rooms that will serve as memorials to the genius of these artists and to which their admirers will make [pilgrimages].