The Phillips has commissioned five plays from local playwrights in response to Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series. The resulting 10-minute, one-act plays will be performed on Oct. 20. In this series, we interview each playwright.

Jacqueline E. Lawton. Photo by Jason Hornick

Why did you decide to get into theatre? Was there someone or a particular show that inspired you?

Jacqueline E. Lawton: My mother introduced me to the theatre through her love of MGM musicals. I was immediately transfixed. The first play that I saw live was a theatre for young audiences touring production of Jack and Beanstalk. It was already one of my favorite stories, because Jack longed for more and ultimately learned the value of what he already had at home. It was magical! I was completely enchanted and knew that I wanted to be part of telling stories in this way. In middle school, I was able to do this through poetic interpretation, and in high school, I was able to take part in the theatre. In college, I was introduced to the professional world of playwriting and solo performance by playwright Amparo Garcia Crow. It was Dr. Oni Olomo Joni Jones who introduced me to performance ethnography and the beauty and complexity of the Black Aesthetic. While earning my MFA in Playwriting, I was introduced to playwright Ruth Margraf, feminist theorist Jill Dolan, and actress Fran Dorn. Each of these women had a deeply profound and lasting impact on my life and artistic journey. It is no exaggeration that I would not be who I am today if it weren’t for them.

Tell us a little bit about your writing process. Do you have any writing rituals? Do you write in the same place or in different places?

JEL: I sit in front of my laptop, stare at the blank page, and ask, “How has anyone ever written a play before?” I ask this, even though I’ve just finished writing a play. From there, I start with the characters. Their names are revealed to me, and I endeavor to learn as much as I can about their hopes, dreams, fears, secrets, and desires. I investigate their worlds and everyday lives. I watch films and documentaries. I read books, articles, and plays. I listen to music and look at art. I learn about their politics, social customs, and food ways. Then I name the play, which in and of itself is quite a process! From there, I outline the structure of the play and start to write. I don’t always follow the outline, but it helps as a guidepost. While writing, I continue to research. Also, I keep a journal and pen with me, because a piece of dialogue, a monologue, or stage directions will come to me at any given moment.

Please share your thoughts on what The Migration Series means to you. What excited you about being a part of this festival?

JEL: In April of 2014, I was invited to join a select group of scholars and practitioners to help shape the interpretation and programming of the People on the Move: Beauty and Struggle in Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series exhibition. I was honored. As a teaching artist, I had used the panels as part of my classes for years. I guided students to create plays, poems, sculptures, and dances based on the panels. I felt it was important for the students to study the history of this country through art. I created this festival to honor the work of Jacob Lawrence and the lasting impact of his great art.

Tell us a bit about your play. What is it about, and what do you hope audiences will walk away thinking about after hearing it?

JEL: My play, A Long Arduous Journey, is about the devastating civil war in Syria. It follows a young woman, Sabeen, who has emigrated to the U.S. with her family. Her brother chose to stay behind and fight for their homeland. While in the U.S., Sabeen meets Malcolm, who helps her update her resume and look for work. He has been out of work for two years, but does odd jobs now and again. Over the course of the play, the two of them learn more about each other and their lives. My hope is that audiences see this play and remember that immigrants coming to this country are searching for a better life for themselves and their families.

Which of the Migration Series panels inspired your play? What drew you to it? What was it like to write a play inspired by a work of art?

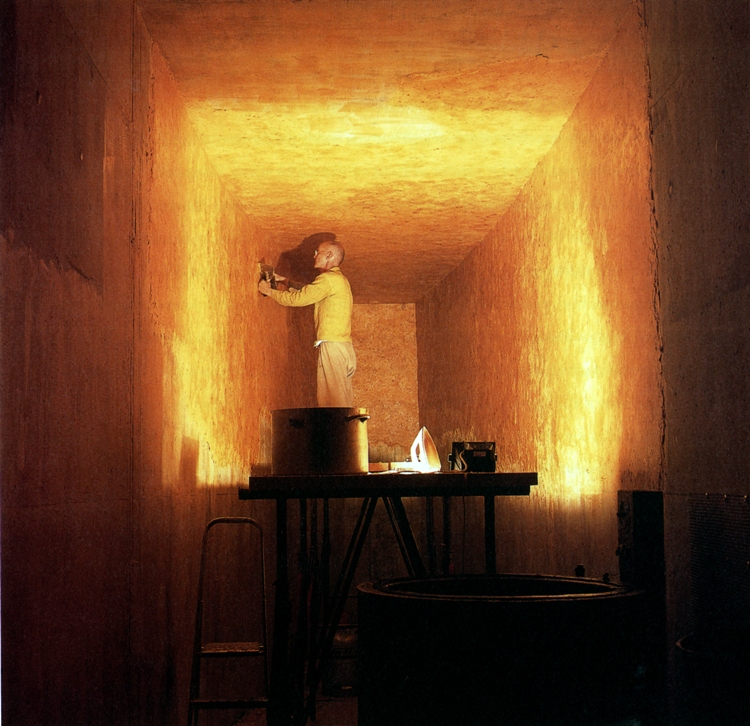

JEL: My play was inspired by panels 57, 13, and 25. Panel no. 57 is my absolute favorite. The woman is determined, focused, and purposeful. It takes great strength to stir all of those clothes. She reminds me of my mother. Panel no. 13, this image of barren land, reminded me of the drought in Syria and the South during the Great Depression as well as the strife that comes when the land can no longer yield fruit and vegetation. Panel no. 25, the image of an empty corner of a room, made me think of the homes that were left empty and unattended both during the Great Migration and also during a war. The process of writing the play based on the panels came quite easily. They already have such a strong, inspiring narrative. I can imagine coming back to these same panels and writing something else entirely.

Why do you think the message of The Migration Series still resonates today? How does your play relate to that message?

JEL: Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series is a masterful piece of art. While capturing the challenges of life in the South and the hope of a better life up in the North, Lawrence captures the harsh realities of migration and a new life that so many faced. He creates a space for the viewer to experience the journey of the migration and that is powerful. I hope that my play does this as well.

What advice do you have for up-and-coming playwrights?

JEL: Be bold, honest, and determined. Have the courage to write plays that show the world the way you see and experience it. You’re the only one who can do that, which makes you absolutely essential to the American Theatre. See as many plays and readings as you can. Make friends with other theatre artists. Talk, argue, complain, yell and cry to them about the kind of work you want to be creating, the kind that isn’t being created where you live, and then go create it. Honor and protect your writing time. Don’t ever stop writing!

What next for you? Where can we follow your work?

JEL: From February 24–April 2, 2017, my play Intelligence will receive a world premiere production at Arena Stage. It’s very exciting! Of course, you can follow me at my website.