[Arthur] Dove’s relationship with my father [Duncan Phillips]—launched, controlled, and sometimes distorted by the redoubtable Alfred Stieglitz—must stand as one of the most interesting and productive artist-patron relationships of modern times . . . Dove was the model of what [my father] wanted most to encourage—the independent artist with a powerful, fresh, and highly personal vision.—Laughlin Phillips

Through correspondence in the Phillips archives, photographs, and more, the Reading Room exhibition Dear Dove, Dear Phillips, Dear Stieglitz explores the relationship between artist, patron, and gallery dealer.

THE EARLY YEARS, 1912-1933

From 1924 to 1933, Arthur Dove lived on a 42-foot-long sailboat, the Mona, with his second wife, Helen “Reds” Torr, who was also a painter. They sailed around Long Island Sound, near Huntington Harbor.

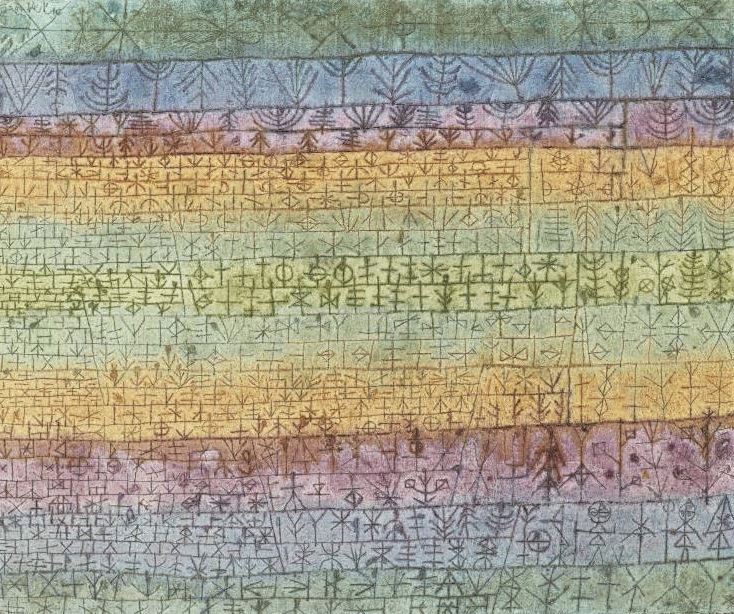

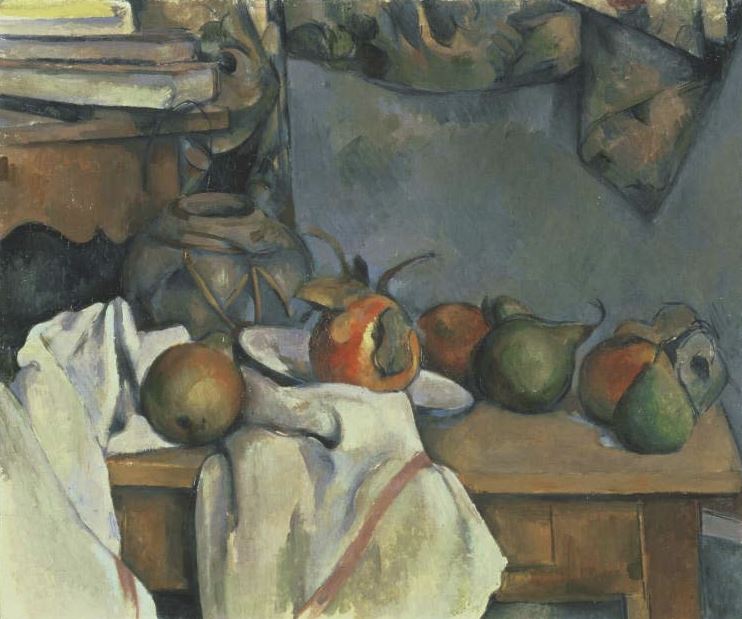

Arthur Dove (1880-1946) grew up in Geneva, New York. He attended Cornell University, where he took classes in pre-law to please his father and studied art to please himself. Following graduation, he became an illustrator, and eventually dedicated himself to painting. In his early work, Dove explored realistic subjects, such as still lifes, but by 1910, deeply influenced by his immersion in nature, he began to work abstractly, creating some of the first abstract paintings in the United States. In 1912, Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946), acclaimed photographer and gallery owner representing Georgia O’Keeffe, John Marin, and Marsden Hartley, among others, became Dove’s dealer.

Beginning in 1930, museum founder Duncan Phillips (1886-1966) became Dove’s patron. He sent Dove a check for 50 dollars a month (which gradually increased to 200 a month) in exchange for first choice of the artist’s paintings that were exhibited at Stieglitz’s gallery. Phillips responded to Dove’s simple way of life and his independence from European art movements. The Phillips Collection gave Dove his first museum retrospective in 1937 and owns 56 works by the artist—the largest collection of works by Dove in the world. Artist, patron, and gallery dealer exchanged hundreds of letters from 1926 to 1946, the year that Dove and Stieglitz died.

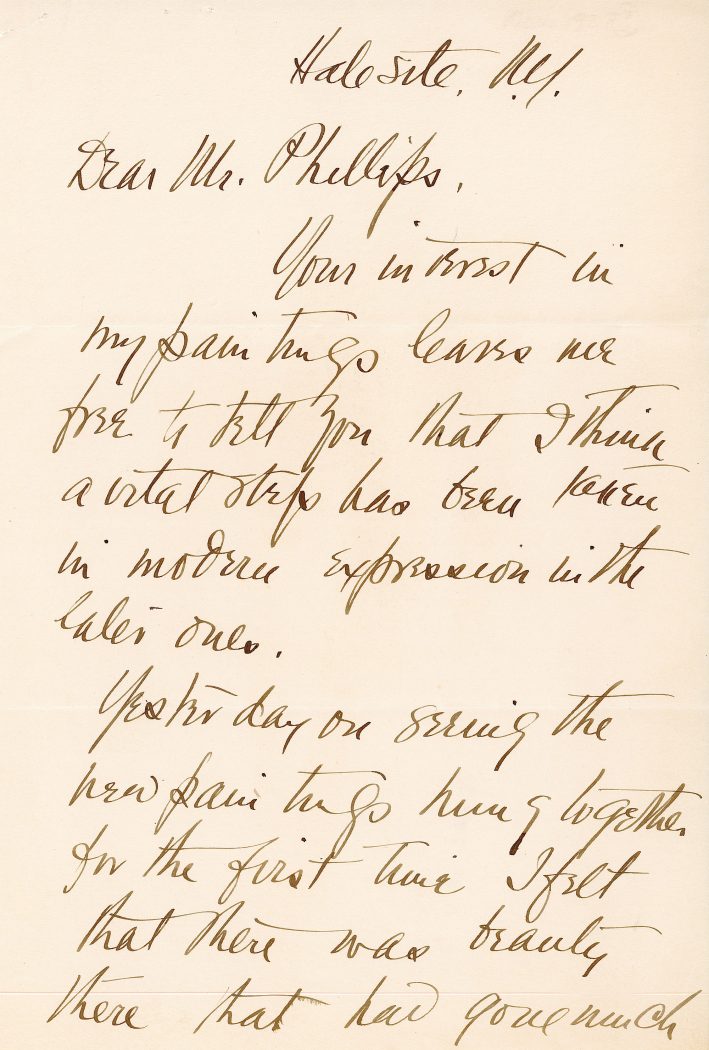

Duncan Phillips to Arthur Dove, December 19, 1927

This is the first letter that Arthur Dove wrote to Duncan Phillips. The artist invited the collector to see his exhibition at Stieglitz’s 291 gallery in New York: “Your interest in my paintings leaves me free to tell you that I think a vital step has been taken in modern expression with the later ones. Yesterday on seeing the new paintings hung together for the first time I felt that there was beauty there that had gone much farther toward a new reality of my own. I feel that you should and will go to see them.”

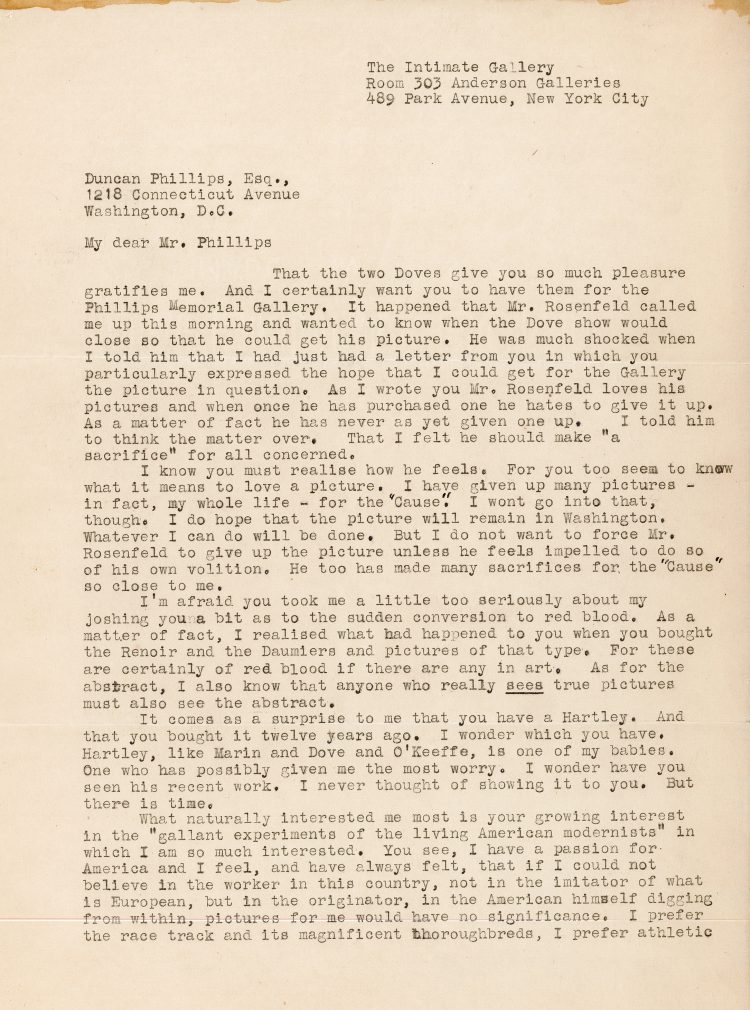

Alfred Stieglitz to Duncan Phillips, February 1, 1926

Alfred Stieglitz and Duncan Phillips conducted a lively correspondence for 20 years. In this letter, Stieglitz aligns himself with Phillips’s growing predilection for innovative work by American artists: “What naturally interested me most is your growing interest in the gallant experiments of the living American modernists in which I am so much interested.” Several years later, Stieglitz reported to Phillips that he felt that the work of Dove, John Marin, and Georgia O’Keeffe was “of greater freshness and significance than anything being done in Europe.”

Arthur Dove, Golden Storm, 1925, Oil and metallic paint on plywood panel, 18 9/16 x 20 1/2 in.; The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1926

Golden Storm (1925) and Waterfall (1925) were created on Dove’s sailboat in Huntington Harbor. Though small in scale due to limited working space, both works suggest the monumental. A suspenseful image of choppy waves raging beneath a threatening sky, Golden Storm reflects Dove’s constant experimentation with new media. He avidly read books on materials and techniques and often ground his own pigments. In this painting Dove made liberal use of metallic paint, creating a subtle, iridescent effect. Phillips expressed concern about the longevity of the delicate surface, but Dove assured him that it would not fade. Golden Storm and Waterfall were the first works by Dove purchased by Phillips and the first paintings by Dove acquired by a museum.

Stay tuned for Part II (The Centerport Years) and Part III (The Geneva Years) of this series and visit the Reading Room to see the exhibition.