In this series, Manager of Visitor and Family Engagement Emily Bray highlights participants in This Is My Day Job: The 2018 James McLaughlin Memorial Staff Show, on view through September 30, 2018.

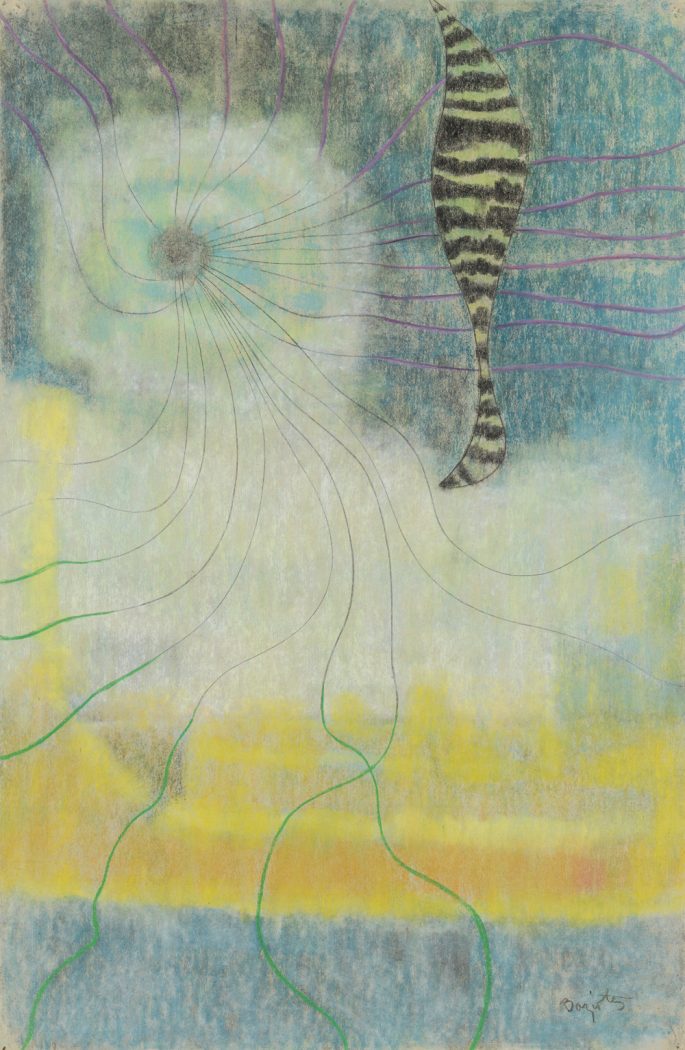

Decontrol by Gregory Logan Dunn

Tell us about yourself.

I create paintings by dragging multiple layers of paint one over the other in order to reveal the layers underneath through the tearing and fracturing of the layers above. It’s to achieve these small areas of color within the larger field that are saturated by the history of this layering. Occasionally the field becomes beautiful and then subsequently must be destroyed. Only through this method can the shallow graves of better angels be revealed.

What do you do at The Phillips Collection? Are there any unique or interesting parts about your job that most people might not know about?

I am a Museum Assistant at The Phillips Collection. I interact with visitors, provide information and directions, and frequently have conversations about the art. Sometimes I engage in these conversations less than two feet away from some very beautiful art. This usually means the person who I am talking to is standing too close to the art because they love it so.

Who is your favorite artist in the collection?

Gene Davis’s Red Devil is my favorite piece in The Phillips Collection. Sam Gilliam’s Petals is also a favorite. I love Bonnard.

What is your favorite space within The Phillips Collection?

I really love the third floor of the Sant Building, right next to the Goh Annex. It has so much space but it still draws you in and has a intimate feel overall. I love the skylight as well.

What would you like people to know about your artwork on view in the 2018 Staff Show (or your work in general)?

This is the first acrylic work I’ve completed in over a year, after spending 2017 and most of 2018 working in oil. I’m working on a number of pieces in acrylic right now and I’m very excited about the work. The speed at which I’m able to work is gratifying, but also exerting because of the dry time. I have less time to work so I am relinquishing some power over the work. That is the source of the title Decontrol. I am giving over some control in the inception of the work in order to foment its creation.

This Is My Day Job: The James McLaughlin Memorial Staff Show is on view through September 30, 2018. Join us for a reception in the exhibition on September 20, 5-7 pm.