Snapshot is part of the National Cherry Blossom Festival, celebrating 100 years of the gift of trees. For readers interested in learning more about the influence of Japan on artists in the exhibition, gallery talks on “Japonisme in France” will be held at 6 and 7 pm this Thursday as part of the Phillips after 5: Journey to Japan event.

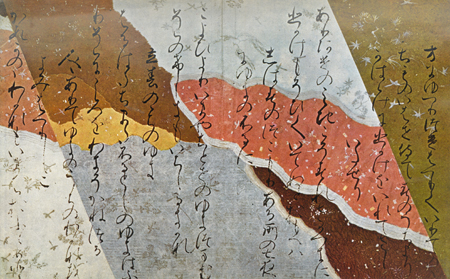

(Left) Woman walking with an umbrella, seen from behind. Reproduction from a Japanese print, published in Le Japon Artistique, March 1891. (Center) Pierre Bonnard, The Little Laundress, 1896. Color lithograph, 11 3/4 x 7 1/2 in. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation) © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. (Right) Attributed to Suzuki Harunobu, 1725-1770. A young woman crossing a snow-covered bridge. Color Woodcut. 1765. The Gale Collection. The Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

Pierre Bonnard was a member of an artistic group called the Nabis, the Hebrew word for prophet. The group, which included Edouard Vuillard and Maurice Denis, were the harbingers of a new way of making art. They broke away from academic tradition to embrace an approach that emphasized decorative unity and a more personal, abstract style. The group members gave each other nicknames; Bonnard’s was “le Nabi très Japonard,” or “the ultra-Japanese Nabi.”

Less than a year after he abandoned law school to pursue a career in art, Bonnard saw a huge exhibition of Japanese prints at the École des Beaux-Arts, where he had been a student. The exhibition featured over a thousand Ukiyo-e woodcuts just when the craze for all things Japanese was at its height in Paris. Bonnard was already looking at Japanese prints at the Goupil Gallery, where Theo van Gogh worked, and bought Japanese prints at a boutique on the Avenue de l’Opera. The prints were available for the equivalent of a few dollars, and Bonnard papered the walls of his studio with them. He purchased works by Hiroshige, Kuniyoshi, and Kunisada.

In Japanese prints, Bonnard found much to inspire him at a key moment in his artistic development: graceful contours, flattened color, asymmetrical compositions, and subjects drawn from everyday life. Bonnard’s The Little Laundress (see above), a color lithograph from 1896, is a prime example of the influence Japanese prints had upon his work. As Colta Ives points out in The Great Wave: The Influence of Japanese Woodcuts on French Prints, the slightly awkward figure with an umbrella, making her way up a street paved with cobblestones, echoes the silhouette of an Ukiyo-e print published in 1891 in Le Japon Artistique (see above), a periodical that Bonnard subscribed to. It also resembles a print by Suzuki Harunobu of a young woman crossing a snow covered bridge (see above). Bonnard found in Japanese art qualities that liberated him from Western conventions of color, form, and composition, creating uniquely intimate, spontaneous works that were aligned with his personal temperament.