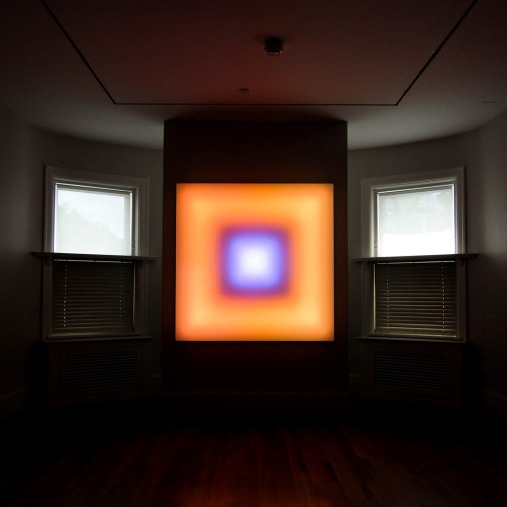

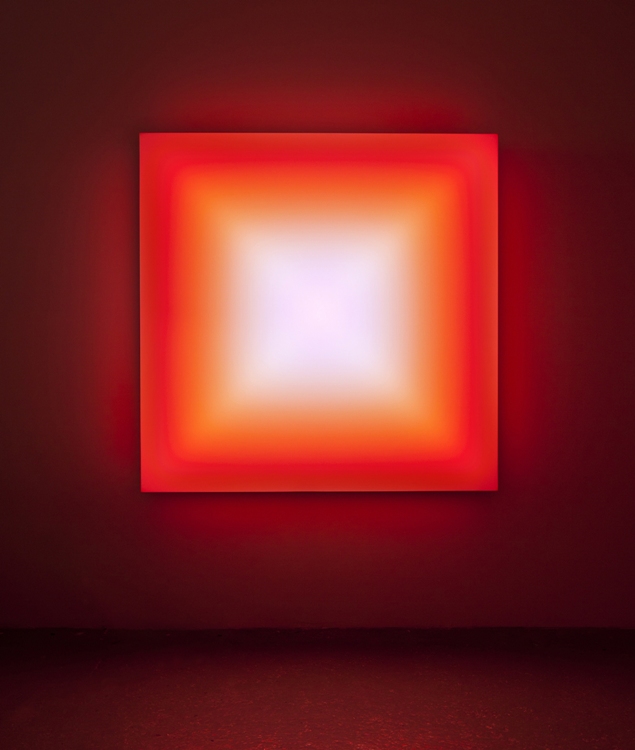

Leo Villareal, Scramble, 2011. Light-emitting diodes, Mac mini, custom software, circuitry, wood, Plexiglas 60 x 60 x 8 in. Ed. 2/3, The Drier Fund for Acquisitions, 2012. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. © Leo Villareal, Courtesy of Conner Contemporary. Photo: James Ewing

As an intern in the Phillips’s education department, I have handled a variety of tasks, most of which allow for a creative approach or solution. When my supervisor asked me to write about something that interested me for this blog, I saw it as an opportunity to connect my interest in art and museums with my interest in interior design. As I walked through the galleries, Leo Villareal’s Scramble (2011) caught my attention–I stood in front of it, captivated by the changing lights. As I researched Villareal’s intent and inspiration, I made a connection between his work and a lighting design class I’m currently taking. I was inspired to look at LED lights from both an artist’s and an interior designer’s point of view and became curious about how LED lights affect the art world.

LED (light emitting diode) lights, were created over 50 years ago. What makes this light source different from halogen and incandescent lights is that it is more energy efficient and has a longer lamp life. Therefore, it is a very sustainable product. This is crucial today, when every industry is beginning to strive to be as sustainable and environmentally conscious as possible. At first LED lights were only available in warm colors, such as yellow, red, and orange, but with time new colors were developed, making LED an extremely versatile light source.

So where will this technology go from here? How is it going to affect art and museums? In most art museums, halogen lights are used in gallery spaces, but with the improvement of LED lights and their energy efficiency, long lamp life, and high color rendering index, LED lighting has been tested and is being considered as an alternative source for museum lighting. One of the biggest concerns in changing lighting in the gallery spaces of museums is the effects it will have on the artwork and the number of hours the art can be exposed to the light before it begins to deteriorate. The Getty Conservation Institute has concluded that LED lights perform slightly better than halogens and will therefore be beneficial in art museums.

Even though these changes are forthcoming, LED lights can already be seen in the work of artists such as Jenny Holzer, Liu Dao, and Leo Villareal. All of these works are installation pieces that cause a sense of awe in the viewer. When asked why he chose to work with light, Villareal explained that while he was getting his master’s degree from NYU in Interactive Telecommunications Programming he realized that he could incorporate light into his work and create an interesting piece with a small amount of information. Scramble pays homage to the work of Frank Stella, who Villareal met at The Phillips Collection. The work is composed of a light box that rapidly changes colors, mimicking the colors found in Frank Stella’s Scramble. Therefore, Villareal’s piece can be understood as a contemporary take on Stella’s work.

LED lights are a new technology that has affected both the medium and the display of art while at the same time adding a sustainable aspect to both.

Veronica Sesana, Education Undergraduate Intern