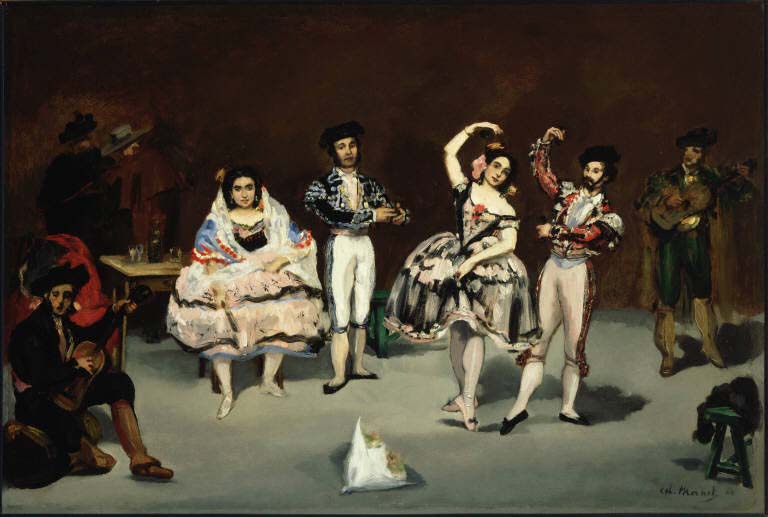

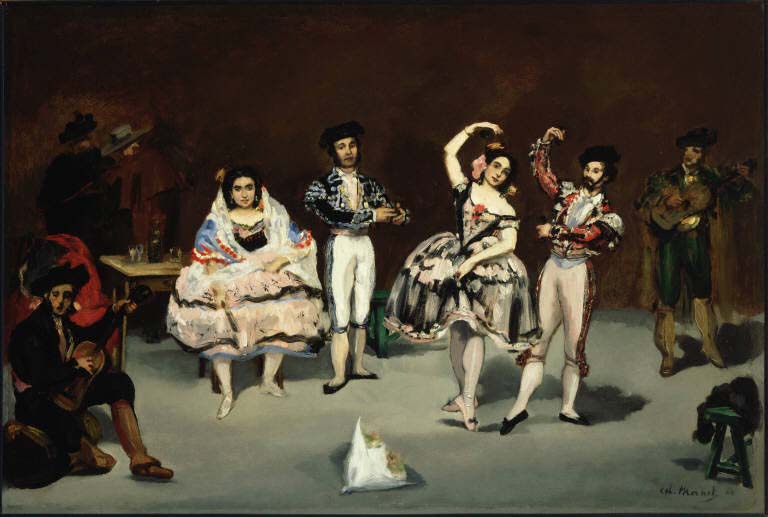

Edouard Manet, Spanish Ballet, 1862. Oil on canvas, 24 x 35 5/8 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1928.

I would like to retreat to a more contemplative mode and share observations on one of my favorite paintings in the collection, Édouard Manet’s great Spanish Ballet, looking deeply and thoughtfully the way the Phillips encourages and fosters. I simply want to reflect on what makes me love this painting, on view with Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party and other European masterworks in a special anniversary installation.

There is a fundamental and exciting tension at its heart. The deep blacks, pearlescent pinks, and dazzling silky whites are sumptuous. The luscious colors contrast with the stumpy figures in awkward poses, accentuated by stark lighting and arranged in a rigid frieze across an ill defined stage. This contrast between seductive color and crude flatness is clearly intentional, as stark as the broad bands of dark and light that define the space, as blunt as the white paper-wrapped bouquet, dead center at the edge of Manet’s pictorial “stage,” at the feet of the dancers.

The dancers’ exotic costumes are beautiful. Horizontal ribbons of blue and black paint define the broad skirt of Lola de Valence, seated at left. With the tip of his tiniest brush, Manet scatters delicate black embellishments across a patchwork of pink, taupe, and gray brushstrokes. The tight britches of the male dancers are formed with long brush marks of white, pink, or gray. The principal dancer, Don Mariano Camprubi, poses at far right. The glistening smoothness of his pants contrasts with the explosive red-black-white-pink of his elaborate bolero jacket. The fiery red is echoed in the flower at his partner’s bodice, in Lola’s shawl, and the fabric draped at far left. A light blue similarly plays across the composition.

There is so much to delight and intrigue in this painting— come see it for yourself and enjoy!

-Dorothy Kosinski, Director

Lola de Valence

Entre tant de beautés que partout on peut voir,

Je contemple bien, amis, que le désir balance;

Mais on voit scintiller en Lola de Valence

Le charme inattendu d’un bijou rose et noir.

— Charles Baudelaire, Les Fleurs du mal (1868)

Among such beauties as one can see everywhere

I understand, my friends, that desire hesitates;

But one sees sparkling in Lola of Valencia

The unexpected charm of a black and rose jewel.

— Translated by William Aggeler, The Flowers of Evil (Fresno, CA: Academy Library Guild, 1954)