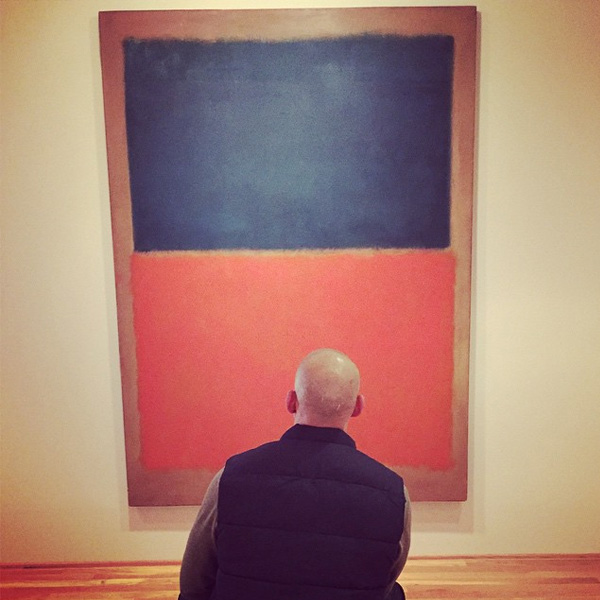

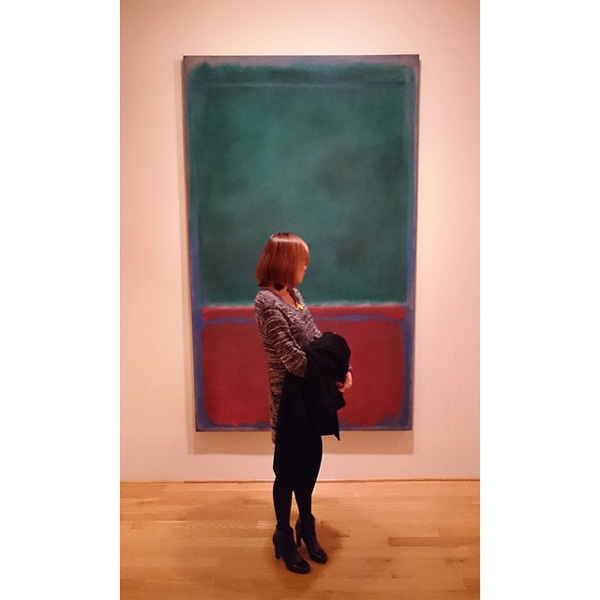

(Left) Rothko Room at The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Photo: Max Hirshfeld (Right) Mark Rothko, Orange and Red on Red, 1957. Oil on canvas, 68 7/8 x 66 3/8 in. Acquired 1960, The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC

Behind the bar at Firefly in Dupont Circle, Jon Harris is to liquor what Mark Rothko was to paint: a true artist. In celebration of the opening of Made in the USA: American Masters from The Phillips Collection, 1850–1970, Jon Harris has created a one of a kind cocktail for the March 6 Phillips After 5, Mad Museum: The American 60s. His cocktail, the Bittersweet Meditation, is inspired by the post-war Abstract Expressionists and more specifically Mark Rothko’s bold use of color and the tranquil space of the collection’s Rothko Room. We talked with Jon a little about his cocktail, the inspiration, and the connection between cocktails and art.

Photo: Stephanie Breijo

Tell us a little about the Bittersweet Meditation cocktail, what is it made with?

It’s made with bourbon, campari, lime, ginger beer, and angostura bitters. Simply pour the bourbon, campari, lime, and ginger beer over ice in a tall glass and dash the top with angostura bitters.

What is the inspiration behind the cocktail?

I was trying to do some color blocking, which is a Rothko thing. The drink has deep hues of red cascading from top to the bottom due to the bitters being dashed on top.

Do you have any thoughts on the connection between art and cocktails?

Drinking cocktails is a precursor to understanding a lot of art. Many artists were/are inebriated regularly in some way. Get on the same level. But otherwise, a thing that a lot of people forget is that drinks (and food, for that matter) are visual arts. You look at it before you smell it and taste it, so it better look good. So you may look to the visual arts to learn how to use color to create moods and effects. You think constantly about how to present things—which type of glass makes the drink look best.

Also, I think about broad strokes and fine strokes a lot, which is derived from painting. Broad stroke drinks use heavy concentrations of several (fairly intense) liquors, whereas fine strokes involves featuring one liquor and small amounts (dashes and spoonfuls) of others to accentuate it. An example of the former would be the negroni, which is equal parts gin, sweet vermouth, and campari, all duking it out in one glass. A fine stroke example would be the old fashioned, which features whisky with a simple dash of bitters, a spritz of lemon peel, and a bit of simple syrup to accentuate the whisky.

Jon Harris will join Firefly Chef Todd Wiss for a special cocktail and plate pairing at this Thursday’s Mad Men-themed Phillips After 5.