Natalie O’Dell, Le Jardin des Tags, 2013, Acrylic paint and Phillips Collection tags

In this series, Young Artists Exhibitions Program Coordinator Emily Bray profiles participants in the 2013 James McLaughlin Memorial Staff Show.

Natalie O’Dell holds an MA in Art History from New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts and previously worked as a freelance research consultant for Hollis Taggart Galleries in New York. Born in Chicago, she applied herself to dance and the visual arts from an early age. While studying for her BA in Art History and Romance Languages at Washington & Lee University, she worked in art conservation, collection management, and exhibition coordination in the United States and abroad. Since moving to the Washington area, Natalie has enjoyed focusing her efforts on creative pursuits.

What do you do at The Phillips Collection? Are there any unique/interesting parts about your job that most people might not know about?

I’m a Museum Assistant, a position that features duties ranging from the mundane to the exciting. Mostly, I help visitors navigate the collection – find the nearest bathroom, locate their favorite artwork, etc. But sometimes people ask me about the history of the collection or pose insightful questions about the art on display. I think my favorite part of the job is observing and interacting with people as they encounter art, especially those who aren’t afraid to challenge the Modernist canon we hold so dear.

Who are your favorite artist/artists in the collection?

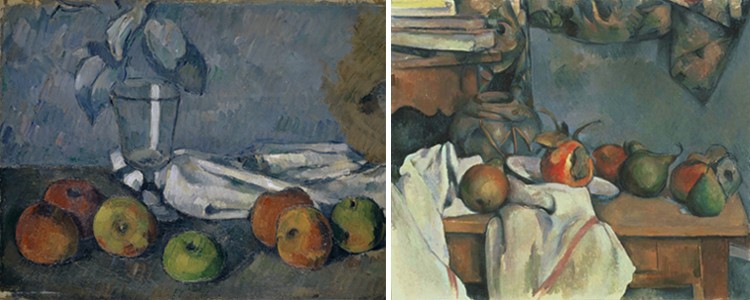

Cézanne. Well, for right now at least … My artwork for this year’s staff show, Le Jardin des Tags, is based on Cézanne’s The Garden at Les Lauves (Le Jardin des Lauves). During my time working as a Museum Assistant I’ve developed a bit of an obsession with this painting. The debate over whether or not it’s finished is largely irrelevant to me. What I find most compelling is the dynamic sense of process – and even struggle – this work embodies.

In Le Jardin des Lauves we see the visible traces of Cézanne’s hand as he searches out the familiar forms of a landscape he returned to again and again. Painted near the end of his life, Le Jardin gives us a rare opportunity to witness the mature Cézanne as he strives to give nature its truest expression in oil on canvas. For me, there is tremendous dignity in this struggle, no matter how tortured it may appear, no matter its level of completion.

(detail) Natalie O’Dell, Le Jardin des Tags, 2013, Acrylic paint and Phillips Collection tags

What would you like people to know about your artwork on view in the 2013 Staff Show (ie: subject matter, materials, process, etc.)?

For my copy of Cézanne’s Le Jardin des Lauves, I decided to incorporate the colored tags we give to museum visitors to indicate whether they have paid the admission fee, hence its name, Le Jardin des Tags (The Garden of Tags). With the help of my fellow Museum Assistants, I collected discarded tags worn by patrons as they visited the collection. I then embedded the tags into the layers of paint, making them a vital part of the work itself and the experience of viewing it.

The tags serve two purposes. First, they highlight the geometric grid structure that underlies Cézanne’s work and laid the foundation for so many formal developments by later artists. The tags also draw attention to the inescapable institutional context of Le Jardin des Lauves. The artwork’s position in The Phillips Collection both directly determines and indirectly affects the viewer’s perception of it, making the relationship between art and institution mutually constitutive. Even when admission is free, it is always regulated; thus access to the work is controlled. Once inside the Phillips the viewer’s estimation of the painting is inevitably influenced by its inclusion (and prominence) in such a world-class collection. Rather than passing a value judgment, I hope to provoke thought about this special artwork and how its institutional setting might affect our perception of it.

The 2013 James McLaughlin Memorial Staff Show will be on view September 23, 2013 through October 20, 2013. The show features artwork from Phillips Collection staff.

Emily Bray, Young Artists Exhibitions Program Coordinator