On Sunday, October 2, 2011, renowned composer Philip Glass performed a concert at The Phillips Collection to benefit the Phillips’s Sunday Concerts and FRESHFARM Markets. Photo: James R. Brantley

American composer Philip Glass has been at the forefront of modern classical music for several decades. A pioneer of what became dubbed “minimalism,” his output is vast and covers a huge variety of media: opera, theater, chamber music, solo pieces, and work for film and television. He is also one of the great symphonists of our time; just this year his Ninth Symphony was debuted by the Los Angeles Philharmonic. His epic four act opera Einstein on the Beach is currently being revived by the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Add that to the prestigious Praemium Imperiale award, given to Glass by the Japan Art Association, and it’s easy to see why 2012 is rapidly turning into a momentous year for the composer.

Glass, however, takes his fame and public image with a grain of salt and is well known for frankness in conversation. In the 2007 documentary A Portrait of Philip in Twelve Parts, he says: “You know, there’s a lot of music in the world, you don’t have to listen to mine. There’s Mozart, there’s the Beatles, listen to something else.” His matter-of-factness is refreshing; it is, after all, born out of rather inauspicious beginnings. He famously drove a New York taxi and worked as a part-time plumber to earn enough to pay members of the Philip Glass Ensemble, the group he formed in 1968 to perform his experimental music. The group is still going strong today.

Philip Glass’s Sunday Concerts 2011 season opener drew a full house to the Phillips Music Room. Photo: James R. Brantley

It was with characteristic coolness and self-assurance that he spoke and performed at the Phillips on October 2, 2011, to open last year’s Sunday Concerts season. Contrary to Glass’s public-facing opera, film, and symphonic work, the packed Music Room was treated to his more inward and poetic pieces for solo piano. He performed six of his Etudes (1994‒); Mad Rush (1979); and four works from the Metamorphosis cycle (1988).

Glass sees his piano music as an intensely private affair, and his performance gave a rare glimpse into that most direct conversation between composition and composer. His works for larger ensemble demand strict rigidity in rhythm and meter, without which the often hypnotic sense of repetition and motion gets lost. However as a solo performer Glass’s playing emerged with more than a touch of romanticism. His extensive use of rubato—the stretching or relaxing of musical phrases and rhythm—and his elasticity with dynamics and pedaling showed just how personal his playing can be. The piano works are rich in polyrhythmic intricacy, but the overwhelming sense of these pieces comes from his use of melody. Glass is a confessed lover of Schubert, and these works are abundant with a sense of Schubertian harmony. In listening to these piano pieces, you feel a sense of lineage with a musical past but are unable to define where it all fits together. His music resists historical imperative.

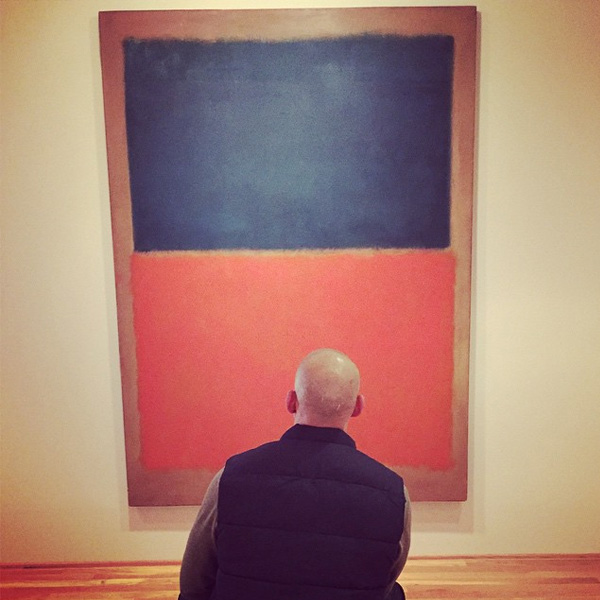

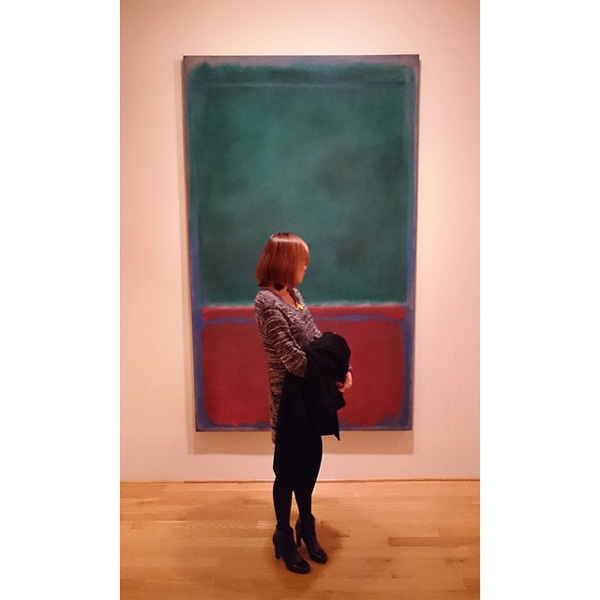

After the concert Glass explained how he is attracted to the ageless quality that music and art can possess, where you may hear, see, or feel an association, but the work of art itself emerges with mystery or detachment from formal understandings. In his visits to the Rothko Room, Glass reflected that Rothko’s canvasses seem at home and at ease on the walls, both now and 40 years ago when he first visited the Phillips as a student. He remarked how they don’t appear to possess a particular or definable age and still feel strikingly modern. Glass’s piano music does too; it evokes the same sense, where finite beginnings and conclusions are obscured, like colors merging into one and other. Music and sound is set within a constant state of motion, moving through an infinite present.

Jeremy Ney, Music Consultant