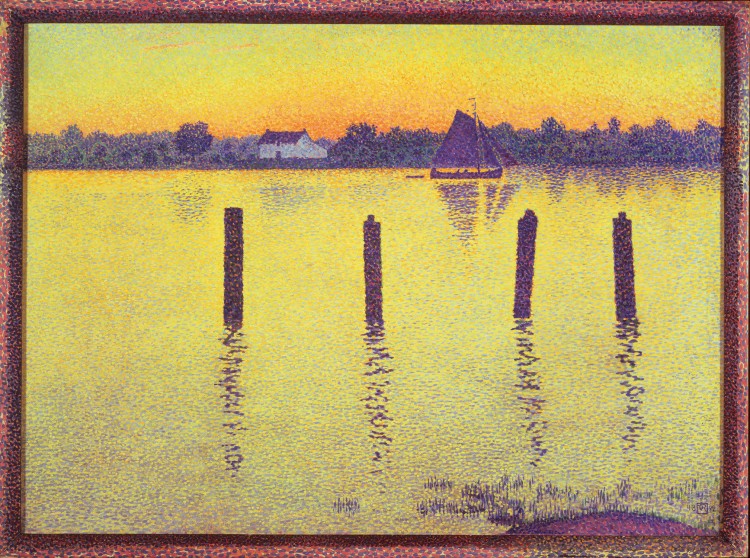

Theo van Rysselberghe, Canal in Flanders (Gloomy Weather), 1894. Oil on canvas, 23 3/4 x 31 1/2 in. Private collection

This year the Art Links: Museum-in-Residence program at The Phillips Collection has expanded by cultivating in-depth collaborations with each of the preschool through sixth grade classes at the Inspired Teaching Public Charter School in Washington, D.C.

I have been lucky enough to work closely with the students and teachers of 1st and 2nd grades. The classroom teachers are indeed inspired and the brilliant students benefit from their teachers’steady conviction, kind hearts, and totally cool ideas.

I collaborated with four teachers to develop lesson plans for my visits to their classrooms. We also collaborated on the tour outlines for each class’s visit to the Phillips.

Harnessing five of the six Prism.K12 strategies, our objectives were that by the end of the lessons, students would be able to:

Identify a setting for a home

Connect the setting to homes for other beings (humans, insects, animals, etc.)

Empathize, Synthesize and Express through discussion. For example: if this is a setting for home, who or what lives there, what do they see, think, smell, hear, taste? What do they feel? What would you feel in this setting? Express thoughts in writing.

We used Prism.K12 strategies along with the school-wide theme of “Home”(motivated by the Inspired Teaching School’s move this year to their permanent “home”at the former Shaed Elementary School) to make connections between the class curriculum and the artwork currently on view at the museum.

The classroom lesson focused on Canal in Flanders by Theo van Rysselberghe, on loan from a private collection for the Neo-Impressionism and the Dream of Realities exhibition. I brought large-scale, color reproductions to school. The students and I sat on the floor and discussed what we saw. We looked closely at the details and tried to imagine that there was a home at the end of the canal, in the far left of the painting. What would that home look like? Who might live there? Who or what might live elsewhere in the scene? People? Fish? Monsters? Worms?

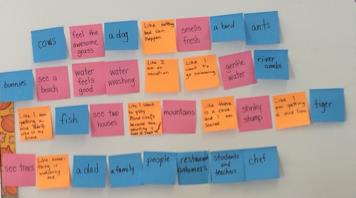

Then we worked together to create a class poem using the flexibility of Post-It notes. We divided into three groups, with two classroom teachers each leading one group and with me in charge of the third group.

This photo of the poem created by Athena Kopsidis’s first grade class. Photo: Carla White Freyvogel.

One group was to imagine who would make a home in the scene of Canal in Flanders. The second group was to identify what you might see, hear, or smell if you made your home in the painting. My group’s assignment was to discuss how living in the painting would make us feel. Our responses were to be written on the Post-it notes and then integrated into a larger class poem.

I was thrilled about my group’s assignment. I knew how the painting made me feel…like wearing a cotton sweater, dropping a blanket on the bank of the canal, pulling out a cheese sandwich, a bottle of beer, and a good book.

But, I am not 6 years old. Anticipating what they would feel, I thought about flying kites, skipping stones, digging for worms, playing tag…

We sat around a small (very small) table and the students shared ideas.

“How does this painting make you feel?”

“Like I want to go swimming”

“Like I am on vacation”

“Like going camping”

I nod. I write their ideas on individual Post-Its.

“Like I want to play Minecraft” a little boy says.

I had not heard this term before but I had my suspicions. I looked at him inquisitively. “What is Minecraft?” I asked.

The kids were dumbfounded that I did not know what this was. They told me it is a computer game. A computer game! A lovely, serene painting of the countryside in Flanders conjured up a computer game? Computer games make me think of drawn blinds, empty bags of Cheetos, a repeated blipping sound as some electronic thingy tags another electronic thingy, and other images that seem at odds with the pastoral scene in front of us.

As museum educators, we know it is most important for our students to make personal connections with the artwork. These connections enhance learning, inspire appreciation of the artwork and the lesson, and ensure memories. But a connection to…a computer game?!

I gently nudged the student to think of something else. I thought he was being silly; just throwing out Minecraft to derail the conversation. I thought that it was most likely that everything made him feel like playing Minecraft.

He was emphatic. “Minecraft. This painting makes me feel like playing Minecraft.”

OK. I told him I would write it on the Post-it note but only if he could tell me why this painting made him want to play Minecraft. I expected this to stump him and we could get down to the business of articulating senses.

He answered right away. He told me that the little dots that van Rysselberghe used in the painting reminded him of the little block-like squares that he uses in Minecraft to create his scenes. The other students whole-heartedly agreed. For them, this added to the feelings that they articulated. They passed no judgement on it being a computer game reference.

I wrote “Like I want to play Mindcraft because the painting is made up of little squares” on a Post-It (yes, I even misspelled Minecraft). And the Post-It took its place among the others in the class poem.

The exercise was a success. The students were thrilled with their poem. They were even more excited when, two days later, they were at the Phillips, seated in front of the original painting. We had a good conversation about their expectations and compared it to the reproduction seen in the classroom. I read the poem they created and they beamed with pride.

Several days later, I walked into a Microsoft Windows store and found myself surrounded by computer screens. Many were illuminated with Minecraft images, appealing to parents shopping for holiday gifts. I had to admit, the student was right! There was a similarity in the vibrant building blocks of the Minecraft scenes and the many Neo-Impressionist dots.

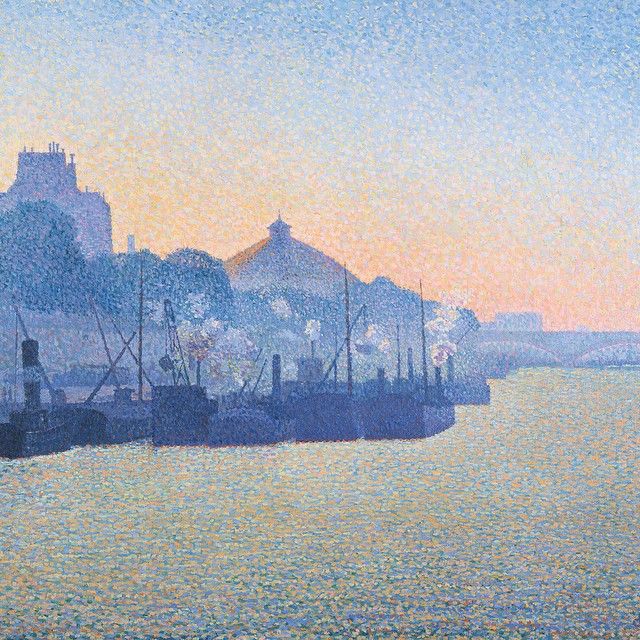

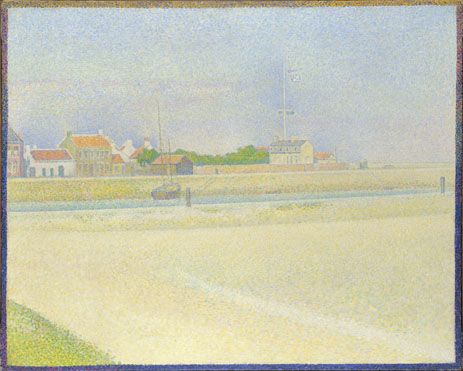

Back at the Phillips, re-visiting the exhibition, I saw the similarity again.

So, I had to ask myself: Who is the teacher?

I really have to admit that the young boy—with his Minecraft comparison—was the teacher in this case. He made an insightful comparison and reminded me to be more open-minded and current as a museum educator.

If he was the teacher, I was the slacker student, sitting in the back row, having not done my homework!

Carla White Freyvogel, School Programs Educator