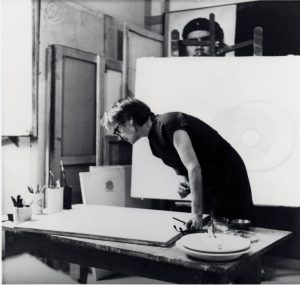

Bice Lazzari in her studio in Rome. Photo: Sergio Pucci

“Bice Lazzari had a unique mind. Her early work was a precursor to abstraction in many ways, as she was always striving to go beyond the usual vision to the next level, seeking the essence, the core of the painting.”-Renato Miracco, curator of Bice Lazzari: The Poetry of Mark-Making (on view at The Phillips Collection through February 24) and former cultural attaché to the Embassy of Italy

Born in Venice, Bice (Beatrice) Lazzari (1900-1981) was a pioneer in postwar Italian art. For most women in the early 20th century, there were limited opportunities to pursue a career in the fine arts. Although trained as a figure painter, Lazzari began her career in the late 1920s in the applied arts, which emphasized a geometric style. In the postwar years, she made Rome her permanent home and it was there that she found her own artistic path. Her paintings of the 1950s are expressive and abstract, while her works of the 1960s and 70s, though increasingly reductive, are highly experimental in materials and have a singular focus on rhythmic mark-making.

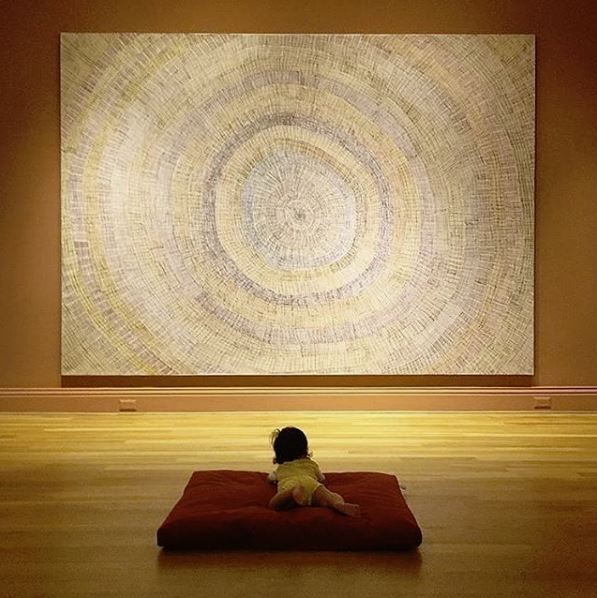

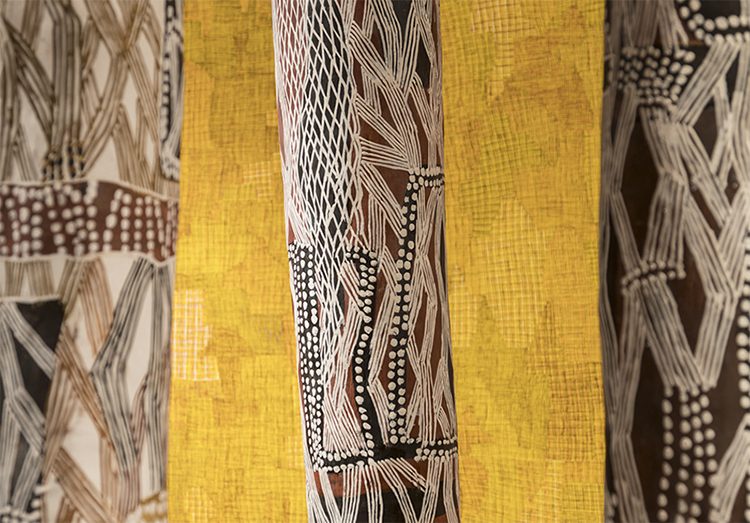

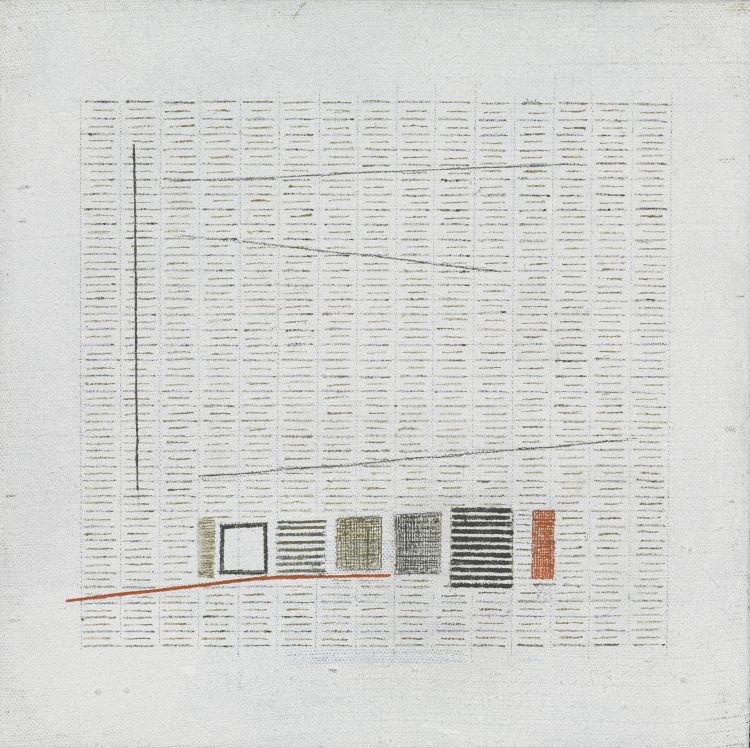

Lazzari’s work resonates with utmost control and minimal gesture. Using pencil, ink, and pastel, Lazzari creates poetic compositions that resemble graphs, maps, musical staffs, and notes. Later in her career, she used acrylics and further simplified her imagery, creating grids, lines, rows of dots and dashes, and irregular shapes using a limited palette. Reflecting her lifelong passion for music and poetry, Lazzari’s lines and forms create rhythms that interact with each other, making her works come alive in a manner akin to musical notation.

Through February 24, The Phillips Collection is proud to showcase four paintings by the artist recently gifted to the museum by Lazzari’s family and the Lazzari Archive in Rome, the first of her works to enter the collection, along with several loaned works on paper.

“Everything that moves in space is measurement and poetry. Painting searches in signs and color for the rhythm of these two forces, aiding and noting their fusion.”-Bice Lazzari, 1957

Bice Lazzari, Sensa titolo, 1974, Acrylic on canvas, 9 13/16 x 9 13/16 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of Mariagrazia Oliva Lapadula and the Archivio Bice Lazzari, Roma 2018, courtesy of the Embassy of Italy, Washington, DC