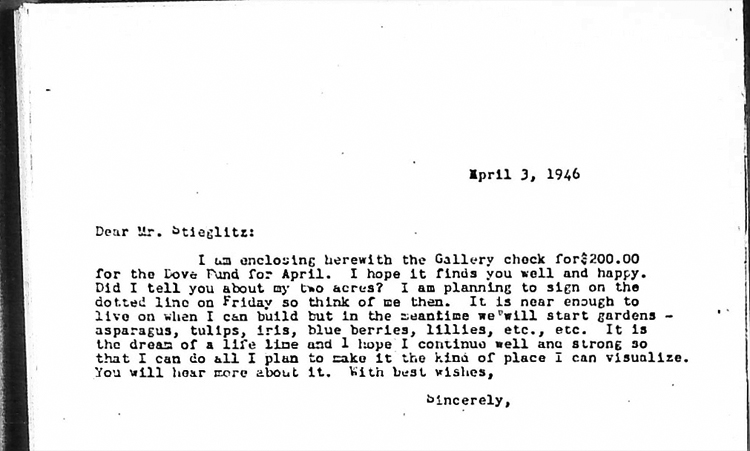

Elmira Bier, in white blouse, sits with C. Law Watkins to her left and Marjorie and Duncan Phillips to her right. Standing are Ira Moore (?) and Charles Val Clear. Photo circa 1931.

Elmira Bier graduated from Goucher College and began working as Duncan Phillips’s secretary in 1923. She went on to direct the music concert series beginning in 1941, encouraging young musicians to expand their repertoire to include works that were off the beaten track. Bier altered the landscape of music in Washington; an article referred to her as “a dominating force in the cultural life of this city.” Bier explained that Phillips had conceived of his museum as “a museum of modern art and its sources,” and she tried to follow this example in her programming, encouraging musicians to include contemporary works in their performances. Bier was not a musician or an artist, but she taught herself about both fields.

When asked to describe her role, music critic Paul Hume wrote that “she ran the place.” Former registrar John Gernand said that her versatility was amazing. On the occasion of her retirement party in 1972, he told her, “You may greet Henry Moore or Kenneth Clark and a few moments later take care of calling a plumber, talking to a musician about his program you have not received, or dictating a letter to a publisher about an unsatisfactory color proof, and doing all this with various and frequent interruptions by telephone, intercom, or one of us in person with a question.”

Kevin Grogan, former curatorial assistant, remembered Miss Bier as “crusty, irascible, and hard-headed. Needless to say, she was loved by all.” Elmira was famous for making a fabulous liquor-filled fruitcake which she would insist on serving before noon in a small, enclosed room “that could give you a contact high like you wouldn’t believe.”

Bier’s devotion to the Phillips was matched by her love of organic gardening. She delighted in the first tomato from her garden, as she did in serving lettuce grown in her cold frame for Christmas dinner. She commissioned architect Henry Klumb to build a strikingly contemporary home on Glebe Road in Arlington, which she shared with her companion, Virginia McLaughlin. Elmira tended the vegetable garden while Virginia took care of the trees and bushes.