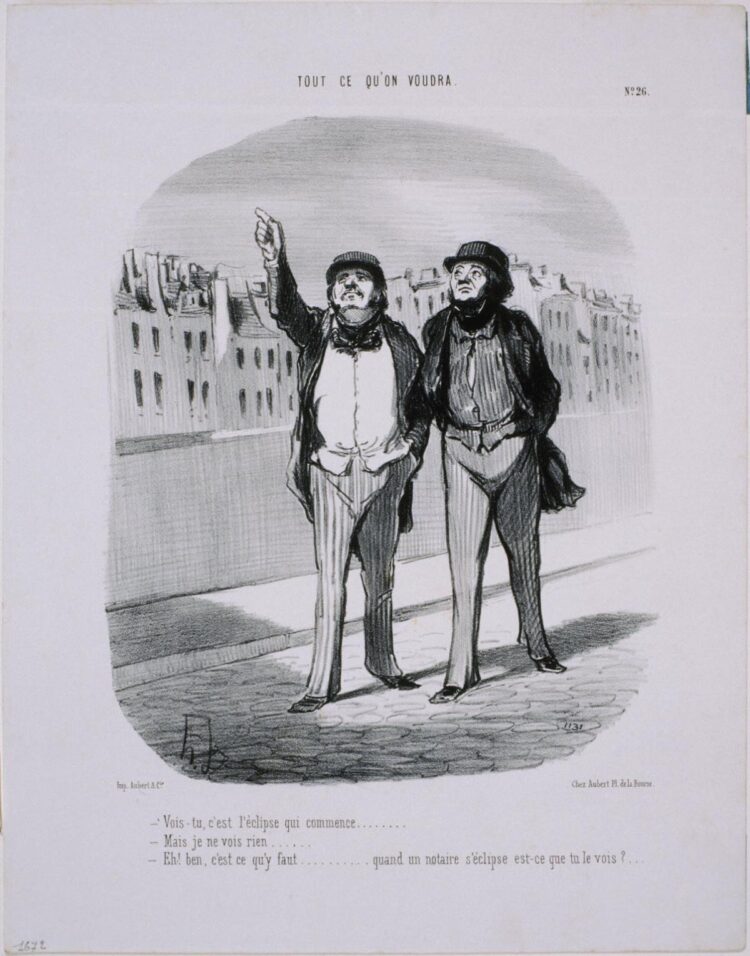

Marketing and Communications Detail Summer Roshni Bhullar takes a look at Honoré Daumier’s lithograph about the eclipse in 1847.

Ancient cultures across time have often believed eclipses are a sign of destruction. They have been interpreted as negative, with the disappearance of the sun symbolizing the sun being swallowed up by darkness. But are they negative or is it fear which leads to this interpretation?

Honoré Daumier, Tout ce qu’on voudra: Vois-tu, c’est l’eclipse qui commence…, 1847, Lithograph, 13 1/2 x 10 1/2 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of Jean Goriany, 1940

Honoré Daumier, born in France, was one of the most rebellious and revolutionary artists of the 18th century. He is well known for his realistic lithographic caricatures among other artistic mediums, created in his groundbreaking graphic style. He worked for a French humor magazine called Le Charivari for over 40 years, making almost 3,900 lithographs and wood engravings for them. He unabashedly expressed his views against society, which he perceived as corrupt and pretentious. He was like a visual reporter, and his art was an outcry for humanity. We can see that if we try to catch the soul of his intention and his satirical and rebellious ways.

The eclipse was the subject of one of his famous lithographic caricatures, ‘Tout Ce Qu’on voudra: Vois-tu, c’est l’eclipse qui commence…’ The satirical image was made during the solar eclipse that occurred over Paris on October 9, 1847. In his signature defiant style, he weaves in current events—in this case the eclipse, which can also be interpreted as something being eclipsed or disappearing.

Daumier constantly rebelled against the government as well as the legal profession. Because he was forced to work in a law office, he strongly disliked anyone working for the law office which included the notary public. In the eclipse lithograph, he seems to be mocking the attention—especially from the media—being given to the eclipse and ties it to the legal profession, linking the disappearance of the notary and the sensationalism created in the minds of the public by the media about the eclipse. Daumier was fearless—which led him to spend some time in jail for speaking against society and the law—and is visually speaking against the herd mentality of the public, and the authorities telling them what to see and not to see.

We live in a world where fear plays a key role. The media, news, government, and society propagate it. Even with eclipses—along with excitement and interest, there is an element of fear which has always played a part. Since the oldest recorded eclipse in human history, which may have been on November 30, 3340 B.C., eclipses as celestial events have been big occurrences. Every culture has an interpretation of them. Some celebrate them, some fear them, some worship them.

What eclipses are—apart from being celestial and astrological events—are reset points. The moon symbolizes our emotions and feelings, and the sun symbolizes life, renewal, and growth. Eclipses happen every six months and energetically they are a time of deep change. Two of the celestial bodies which impact us so deeply, when their light is ‘turned off’ for a few brief moments—means it is time to realign, reset, and let go of the old and usher in the new. They generally happen in a pair—a lunar and a solar eclipse. It is like an emotional culmination and energetic renewal.

Daumier continuously rebelled against aspects of human psychology which led to more fear and lack of freedom. His art and rebellion were an attempt on his part to help the public see the truth through his art.