Community Engagement Assistant Alani Nelson reflects on the land, its lost histories, and the journey toward recovery, using Let Them Enter Dancing and Showing Their Faces, Thief by Nicholas Galanin as a starting point.

Nicolas Galanin is an artist of Tlingit and Unangax̂ heritage living in Sitka, Alaska. His practice honors “the land.” Sitka is right outside of the state capital, Juneau, a pivotal site for gold mining during the last decades of the 19th century. After the United States purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867, the discovery of gold irrecoverably altered the relationship between the Tlingit Nation and the land. While the Tlingit and the Haida are indigenous to the land that we now call Southeast Alaska, the United States government did not permit them to file land claims during a time of unprecedented economic change. This land has been the stage for a series of historic events marred by the exclusion of those Indigenous people who have been its steward since time immemorial.

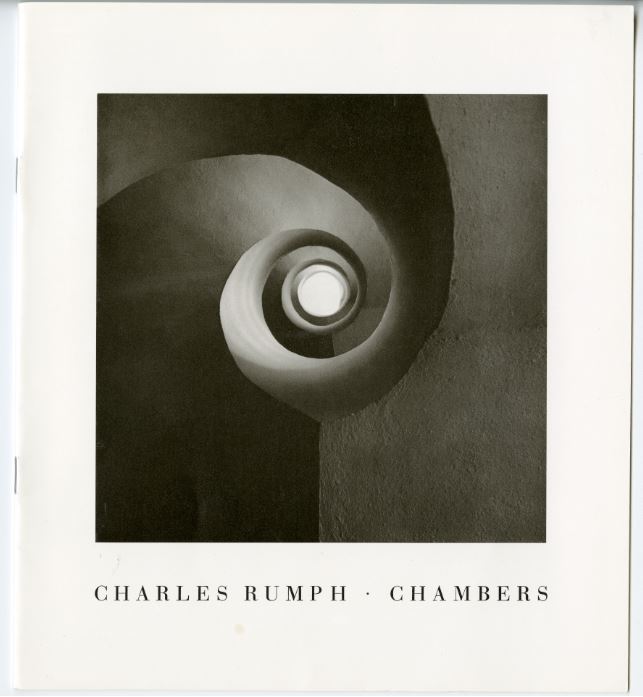

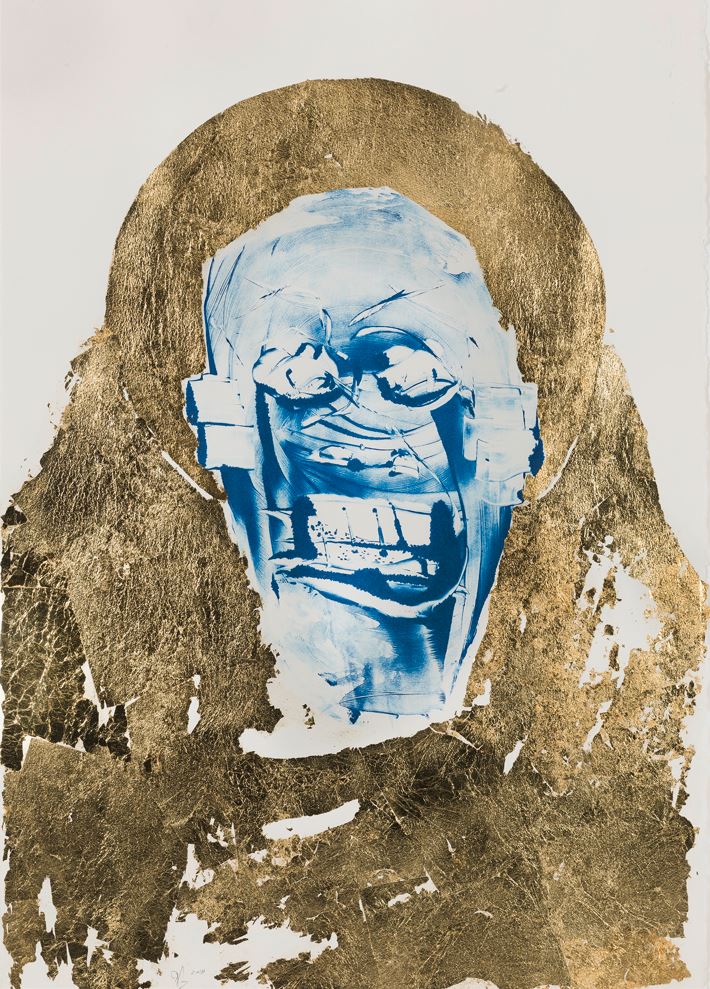

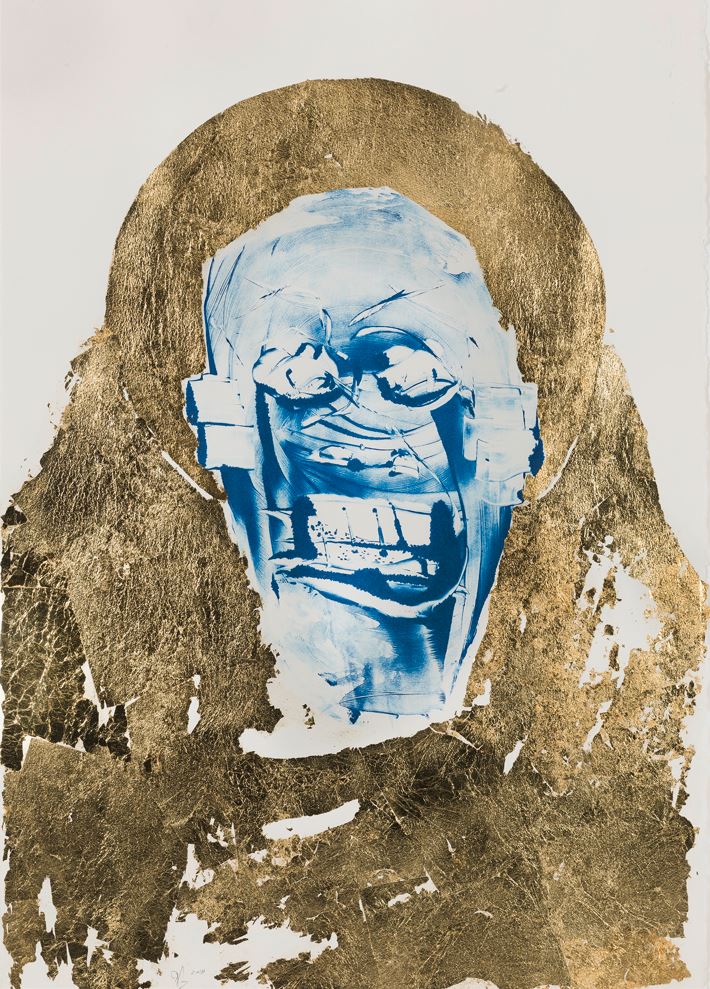

Galanin’s Let Them Enter Dancing and Showing Their Faces, Thief, with its almost frenzied expression, greeted me on my first day as an employee at The Phillips Collection. Adorned with a halo gilded in gold, it cut into my view and soon became the reason I would walk roundabout ways to my office or hover for a second too long in the Music Room where it was displayed.

Nicholas Galanin, Let Them Enter Dancing and Showing Their Faces: Thief, 2018, Monotype and gold leaf on paper, 30 x 21 in., The Phillips Collection, Director’s Discretionary Fund, 2021

Shortly after viewing Thief, I asked to lead a spotlight talk on Galanin’s work for one of our weekly virtual meditations. I knew that acknowledging the Indigenous people whose land we now reside on was necessary. While going over my presentation for a friend, they stopped me mid-introduction to let me know that the land acknowledgment, which referenced the Piscataway people, did not include all the communities that are indigenous to the region. I instinctively defended the information laid out before me, but it is good to have friends like mine who do not let much slide. We did the research together on Facetime and learned that this land was once the home of both the Piscataway and Nacotchtank (Anacostan) people. After making the alterations to my land acknowledgment in the presentation, I found myself swiftly adapting to the routine of my new role.

Later in the year, the Phillips’s Center for Art & Knowledge hosted scholars from the University of Virginia for the W. Wanambi Distinguished Lecture at The Phillips Collection. In preparation for the lecture, they informed the Phillips team that our land acknowledgment differed slightly from theirs. Our DEAI team embraced the UVA scholarship and began the necessary work to update our land acknowledgment. As part of their journey toward amending the land acknowledgment, the DEAI team sought out leaders from local Indigenous groups and received guidance on which groups should be included in the museum’s land acknowledgment. This brought me back to my early days here. I reflected on my role and the responsibility that comes with being a museum worker. Leveraging the privilege that comes with being a part of museums that hold histories also entails recognizing the responsibility to share these cultural narratives with the world.

In the spring, Thief moved from the Music Room up to the third floor into a new context and conversation with the works in the exhibition Pour, Tear, Carve: Material Possibilities in the Collection. The corner of the gallery glowed as light danced on the gold leaf of Galanin’s work. And shortly after, the digital wall at the museum’s entrance would glow with a new land acknowledgment front and center:

The Phillips Collection is a community of artistic expressions of diverse people, situated on the ancestral and unceded homelands of Piscataway and Nacotchtank (Anacostan) peoples. The area we know as Washington, DC, was rich in natural resources and supported local native people living there. We pay respect to their Elders, past and present. It is within The Phillips Collection’s responsibility as a cultural institution to disseminate knowledge about Indigenous peoples and this acknowledgment reminds us of the significance of place and the museum’s commitment to building respectful relationships with those who call these lands home today.

Let Them Enter Dancing and Showing Their Faces, Thief is part of a larger series of monotypes. Other titles include Knowledge, Sister, Shaman, Mouse, Fortitude, Xóots, Birth of a Song, Soothsayer, Keet, In Trance, Guwakaan, Descendant, Dance, and Central. Of this series, Galanin says, “Some of the faces being revealed in dialogue with my works are not just dancers, but faces within the society we dance in.”[1] The title of the series recalls an ancestral dance, where dancers enter unmasked with their faces revealed.[2] By representing the characters of this dance Galanin creates a space for remembering and creating community. He states:

“The goal of colonization is often consumption and extraction, and then it just continues on. But it’s through memory and connection to places—and sharing that memory and connection—that we can demonstrate, share, and educate about ways of being in a world that are healthy for not just us but our future generations.”[3]

The gold leaf that forms a nimbus around the head of Thief recalls the artist’s reliance on the land as a part of his practice and the history that the land preserves. Let Them Enter Dancing and Showing Their Faces, Thief is a work that considers the nature of history-making and the power of expression to illuminate histories.

As we honor the Piscataway and Nacotchtank (Anacostan) land on which The Phillips Collection resides, let us remember the privilege of arts institutions to bring obscured histories to audiences.

Notes

[1] Nicholas Galanin – monotypes. Peter Blum Gallery. (n.d.). https://www.peterblumgallery.com/viewing-room/nicholas-galanin/summary-of-artworks?view=slider#:~:text=I%20would%20like%20to%20think,the%20society%20we%20dance%20in.%E2%80%9D

[2] Ibid.

[3] Battaglia, A. (2020, March 10). Ancient to the future: Nicholas Galanin aims to change how indigenous art is understood. ARTnews.com. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/artists/nicholas-galanin-peter-blum-gallery-1202677789/