Vradenburg Director & CEO Jonathan P. Binstock shares his favorite moments from 2023.

As we near the end of 2023, the time is right to reflect on all the great work that the Phillips has accomplished over the past year, and tell you all how honored I am to have been a part of it. I’m sharing here a few of my favorite moments, but of course there are so many more. Thank you for warmly welcoming me back to Washington and into the humbling role of Vradenburg Director & CEO. I am grateful for all the support I have received over the past year. I hope to see you in 2024 frequently in the galleries and at our events. I wish everyone a festive and bright holiday season and happy new year!

Exhibition curators Camille Brown and Renee Maurer at the opening of Pour, Tear, Carve: Material Possibilities in the Collection. Photo: Ryan Maxwell Photography

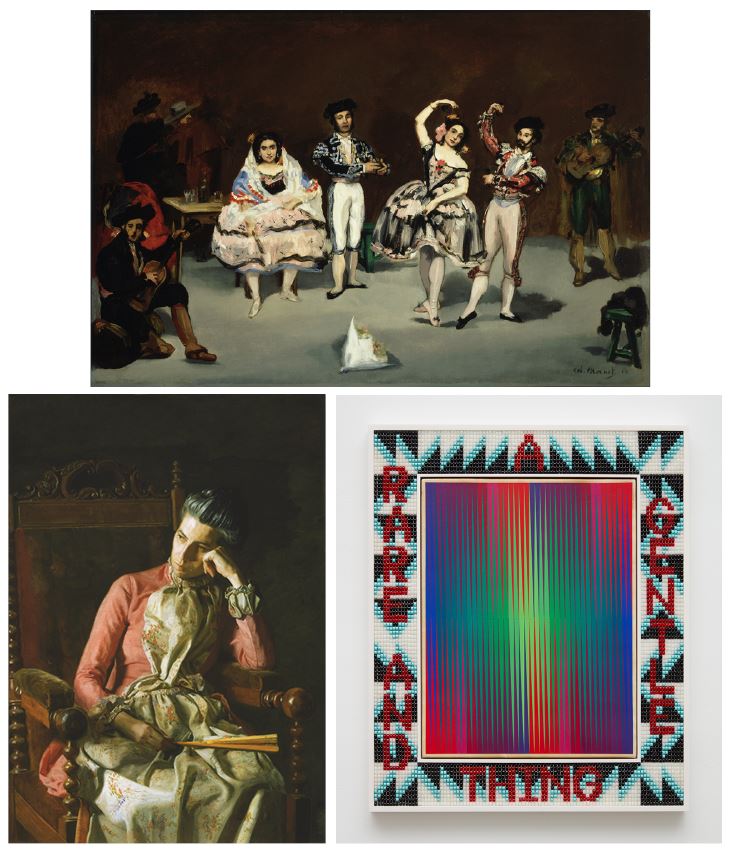

March: Pour, Tear, Carve: Material Possibilities in the Collection opened two weeks after I began my tenure at the Phillips. By highlighting many recent acquisitions, the exhibition—curated by Camille Brown and Renée Maurer—showcased the museum’s efforts to diversify its collection. I was thrilled to learn about so much new work in the collection, and deeply impressed by how the collection could evolve in exciting ways and simultaneously strengthen the legacy established by our founder, Duncan Phillips.

Jay Campbell and Conrad Tao performing in Linling Lu: Soundwaves exhibition. Photo: Dominic Mann Productions

April: I am consistently blown away by the caliber and creativity of our Phillips Music programs. It is one of the great discoveries (for me) and pleasures of my new role—especially because I’m very much a classical music novice. In April, Conrad Tao and Jay Campbell presented an immersive concert in the Linling Lu: Soundwaves exhibition. Soundwaves was inspired by a 2015 Phillips Music performance of Philip Glass Etudes by Timo Andres. Campbell and Tao performed a work by Catherine Lamb, co-commissioned by the Phillips and inspired by the art and ideas of Paul Klee. What a magnificent intersection of visual art and music!

Dee Dwyer at the opening celebration of her exhibition Wild Seeds of the Soufside. Photo: Dorothy Francis

May: The exhibition of photographs by Dee Dwyer at Phillips@THEARC was a wonderful celebration of Southeast DC. The closing event featured a Go-Go band, art activities, and more. I’m very excited about all the exhibitions and events we present at THEARC, and amazed by the quantity and richness of the partnerships we have developed there with our fellow ARC organization. More than working with and helping to build community around THEARC, which is a dynamic, powerfully vibrant, and growing organization, we are an integral part of the community, and, I’m proud to say, we are perceived that way.

Phillips staff with museum colleagues in the Phillips conservation studio. Photo: Jonathan Binstock

May: It was Cézanne study day, and for 15 minutes I was in art historian heaven, mostly a fly on the wall listening to a team of Cézanne experts rhapsodize on the subject of finished vs. unfinished (does it matter?), the existential (representational?) value of a brushstroke, and on. The stellar group included Lilli Steele, Phillips head conservator, Patti Favero, Phillips conservator, Renée Maurer, Phillips associate curator, Anne Hoenigswald, National Gallery of Art conservator, Barbara Buckly, Barnes Foundation head of conservation, Jayne Warman, art historian and catalogue raisonné author, and Kim Jones, National Gallery of Art curator of French paintings. Don’t miss our Cézanne exhibition in April that will highlight their findings.

Jonathan Binstock with his wife at the Capital Pride Festival

June: It was fun to work the Phillips’s booth at the Capital Pride Festival and talk to people about the museum. Many stopped by to tell us how much they love the Phillips and have been visiting for decades, and others heard about the Phillips for the first time. The Phillips is such an integral part of the city, making it all the more important that we show our support for the LGBTQIA+ community.

Inspired by Frank Stewart’s use of reflective elements, three Washington School for Girls students use handheld mirrors in their portraits.

June: Focal Point: Shifting Perspectives through Photography was an exhibition featuring artwork created by Washington School for Girls, Turner Elementary School’s Medical & Educational Support, and Jackson Reed High School Photography Club students inspired by Frank Stewart’s Nexus. The exhibition showcases our continued work with local schools through our Art Links program and Prism.K12 teaching strategies. Through the program the students learned about self-expression, light, movement, creativity, and so much more. And the receptions to celebrate the students and their contributions, along with family and friends, were a ball! I love the bold, striving energy our educators help generate in the students we engage. It’s inspiring.

Creative Aging participants responding to Frank Stewart’s Nexus: An American Photographer’s Journey, 1960s to the Present with Nancy Havlik’s Dance Performance Group

June: During the Frank Stewart-inspired Creative Aging session in the galleries, participants from Iona’s Washington Home Center and Wellness & Arts Center connected to Stewart’s themes and artistry through dance, music, poetry, and drawing. Participants responded to Nancy Havlik’s Dance Performance Group and Miles Spicer’s jazz and blues guitar. This program shows the very direct connection between art and wellness. There was so much joy in the galleries. It’s impossible not to feel—in a moving and visceral way—the positive impact our Creative Aging programs on individual participants. The work we do in this space is incredible.

Left to right: Curator Ruth Fine, Frank Stewart, Hortense Spillars, Fred Moten, Jonathan Binstock

August: In August, to celebrate the final weeks of our fantastic Frank Stewart retrospective, I was humbled to attend the panel with four incredible contributors to the humanistic enterprise: Stewart himself, poet and theoretician Fred Moten, legendary literary and cultural interrogator Hortense Spillers, and the amazing curator and scholar Ruth Fine. Here I am with a bigtime star-eyed emoji face!

Kwaku Yaro, Alidu, 2022, Acrylic, woven nylon and burlap on polymer, 87 3/4 x 60 1/4 in. Photo: Jonathan Binstock

September: During a trip to Europe, I was able to visit the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in London. It’s rare that I fall in love so quickly with art I’ve never seen before. The collages of Kwaku Yaro featuring commonly used plastic carry bags purchased in Accra, Ghana, where he lives, and applied to plastic jute-like mats, grabbed me immediately. The Phillips is actively working to acquire more art by international artists, and I’m thrilled to share that we have just acquired a stunning work by Yaro, Alidu (2022).

The Rothko Room temporary installation with loaned paintings from the artist’s family. Photo: Lee Stalsworth

October: Our Rothko Room is the only room created in collaboration with the artist himself that he was able to experience firsthand. In October, three of the four paintings in that room were loaned to the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, and in their place the artist’s family loaned us three incredible works from their collection. I was lucky enough to go see our works in Paris in the major Rothko retrospective on view there, which you must see if you can. There will never be another like it. Transformational. And if you love yellow the way I do, don’t miss the present, temporary reiteration of our Rothko Room.

Jonathan Binstock with Ugo Rondinone in his One-on-One exhibition. Photo: AK Blythe

November: The Phillips does such spectacular work connecting the art of the past with the art of the present—an important tenant of Duncan Phillips’s vision for the museum. I was delighted to meet the internationally renowned artist Ugo Rondinone—I’m a big admirer—during the installation of his One-on-One exhibition, which juxtaposes his work with that of Louis Eilshemius, a rather obscure and mysterious painter and poet loved by Duncan Phillips and Rondinone himself.

Sylvia Snowden’s studio. Photo: Jonathan Binstock

November: I visited artist Sylvia Snowden in her home on M St. NW in Washington, DC, where she has lived for more than 40 years and where she paints canvases on the floor of every room except the kitchen and bathrooms. I first learned about Snowden’s art in graduate school from my academic advisor, Sharon F. Patton. Artist Sam Gilliam introduced me to Sylvia in the mid 1990s. How fortunate I am to meet such incredible artists and to develop relationships with them over many years. The Phillips is integral to the lives our DC artists, and we are grateful to have the opportunity to encourage, support, and honor them. Sylvia Snowden will be an honoree at our 2024 Annual Gala. I hope you will join and help us celebrate her extraordinary accomplishments.

Installation view of An Italian Impressionist in Paris: Giuseppe De Nittis. Photo: Lee Stalsworth

December: When the Washington Post published its top-ten list of exhibitions for the year, the Phillips was the only DC museum included, for our amazing exhibition, An Italian Impressionist in Paris: Giuseppe De Nittis. Way to go team! And what a terrific way to celebrate the Holiday Season!

Best wishes to all, Jonathan