As any visitor to The Warmth of Other Suns: Stories of Global Displacement will see, the experience of displacement is a global one, rooted throughout history and continuing to present day. As American citizens, it is woven into our shared experience that we, a nation of immigrants, represent all races, ethnicities, and countries. However, we often overlook the internal displacement of peoples within our borders, both forced and willing, throughout our difficult history.

Through the epic Migration Series by Jacob Lawrence (b. 1917, Atlantic City, New Jersey, USA; d. 2000, Seattle, Washington, USA), the Phillips has been telling the story of the Great Migration since the 1940s. Rhythmic, heartfelt, and important—Lawrence’s work illustrates the movement of African Americans from the South to the North in the first half of the 20th century, seeking better opportunities and living conditions for themselves and their families. A cornerstone of the Phillips’s permanent collection, this series offers a gateway to other works on display in the same gallery.

Installation view of The Warmth of Other Suns: Stories of Global Displacement. On the walls left to right: Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series (1940-41), Nari Ward’s Breathing Panel, Oriented Right (2015), and Benny Andrews, Trail of Tears (2005). In the center: Beverly Buchanan sculptures

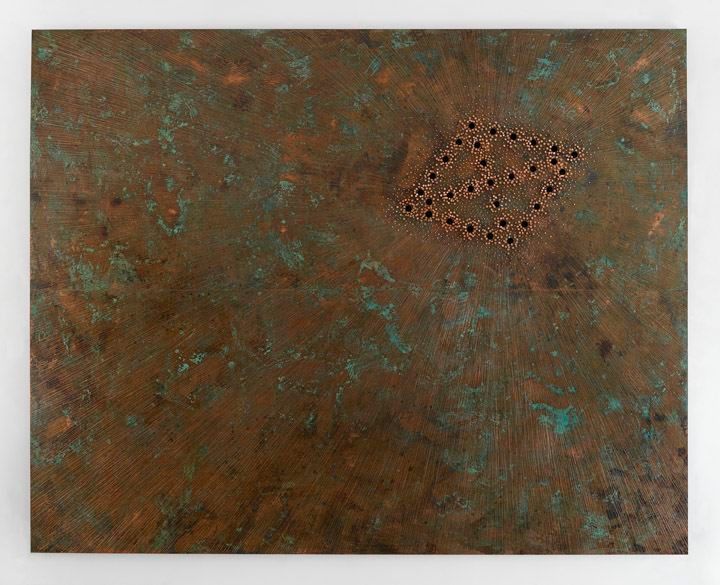

Another important movement of African Americans northward—the Underground Railroad—finds representation in Breathing Panel, Oriented Right (2015) by Nari Ward (b. 1963, St. Andrew, Jamaica; lives in New York City, USA). Ward was inspired by the Congolese “cosmograms” inscribed in the floorboards of the First African Baptist Church in Savannah, Georgia, an important stop on the Underground Railroad. The “cosmograms,” ancient prayer symbols that represent the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, not only informed the church’s enslaved parishioners that this was a gateway to freedom but also provided them an airway as they hid beneath the floorboards during the day until they could safely flee under cover of night. Ward’s copper-paneled piece is all about movement and transformation: the movement of slaves from south to north, the exhalation of breath from below floorboards to above, the rebirth of a slave as a free person at the end of their journey northward, and the transformative performance of the artist, who applied darkening patina to the bottoms of his shoes and stepped on the copper, leaving behind a trace, a memory of the movement.

Nari Ward, Breathing Panel: Oriented Right, 2015, Oak wood, copper sheet, copper nails, and darkening patina, 96 x 120 x 2 1/4 in. Collection of Allison and Larry Berg, Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul

Detail of Nari Ward’s Breathing Panel: Oriented Right

The center of the gallery is populated by five small, ramshackle structures by Beverly Buchanan (b. 1940, Fuquay, North Carolina, US; d. 2016, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA). Buchanan was inspired by the vernacular architecture of the rural south, where she lived most of her life. The sculptures echo the homes depicted in Lawrence’s Migration Series that were left behind when migrants moved north, acting as memorials and remembrances that still stubbornly stand in resistance to time and change. Buchanan tells a story through these structures, often titling works after real people and imbuing them with stories about imaginary and real-life inhabitants. Like Ward, Buchanan documents the movement of peoples by the traces they leave behind—symbols and memories of displacement, injustice, racism, and the hope of progress.

Works by Beverly Buchanan left to right: Room Added, 2011, Wood, 20 x 17 3/4 x 17 1/4 in., Courtesy of Andrew Edlin Gallery, New York; Two Chairs, n.d.; Wood, 12 x 20 x 10 in., Collection of Martin and Rebecca Eisenberg; No Door, No Window, 1988, Wood and acrylic, 14 1/2 x 9 x 7 1/2 in., Private collection, Courtesy of Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

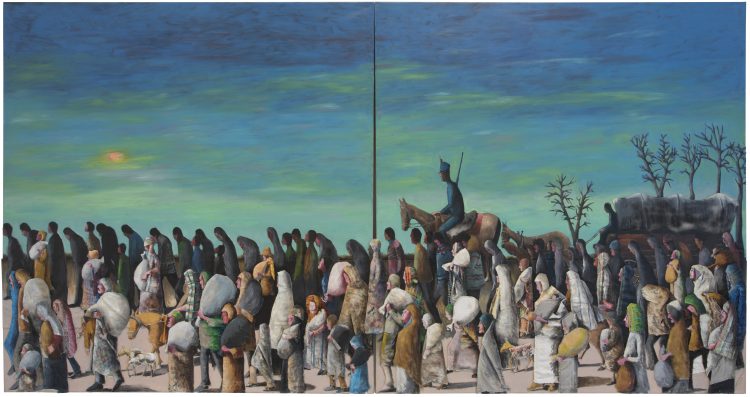

Benny Andrews (b. 1930, Plainview, Georgia, USA; d. 2006, New York City, USA), who, like Buchanan, also grew up in the south, utilized his own background as a son of sharecropping parents to approach themes of mass displacement in US history. Completed during the time Andrews was traveling to New Orleans and the gulf coast to study the areas devastated by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Andrews’s Trail of Tears illustrates the long history of marginalization and displacement of minorities that continues to this day. His process is long and painstaking, building his scenes from layer upon layer of painted canvas and fabric, and includes, like Ward, a sort of performance. Andrews would roam his studio seeking out whatever fabric or shape called out to him and would often cut figures or images out of past canvases. This method created a remarkable blend of textures, colors, and shared experience between his work.

Benny Andrews, Trail of Tears, 2005, Oil on four canvases with painted fabric and mixed media collage, 72 x 144 in. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York

Detail of Benny Andrews, Trail of Tears

The Warmth of Other Suns: Stories of Global Displacement is on view at The Phillips Collection through September 22.

-Liza Strelka, Manager of Exhibitions