Get to know The Phillips Collection’s new Vradenburg Director & CEO Jonathan P. Binstock.

Jonathan P. Binstock is The Phillips Collection’s seventh director. Photo: Margot Schulman

What drew you to The Phillips Collection?

Between 1994 and 1998, I lived at 1724 21st Street, just a block-and-a-half north of the Phillips. I was working at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) and researching and writing my PhD dissertation on Sam Gilliam. That’s when I was first drawn to the Phillips, and I have been in love with it ever since. It was more than the world-renowned collection that enchanted me. My connection to the place was personal—just as it is for so many others. As an admittedly depressed, procrastinating graduate student, the Phillips was a guilt-free distraction, a place to indulge my love for art outside of my work and research. As much as I love visiting almost any art museum, and as much as I owe SAAM for providing me with the best possible professional training, the Phillips was my museum. It nurtured me during a difficult time in my life.

What will be your top priorities as the Vradenburg Director & CEO?

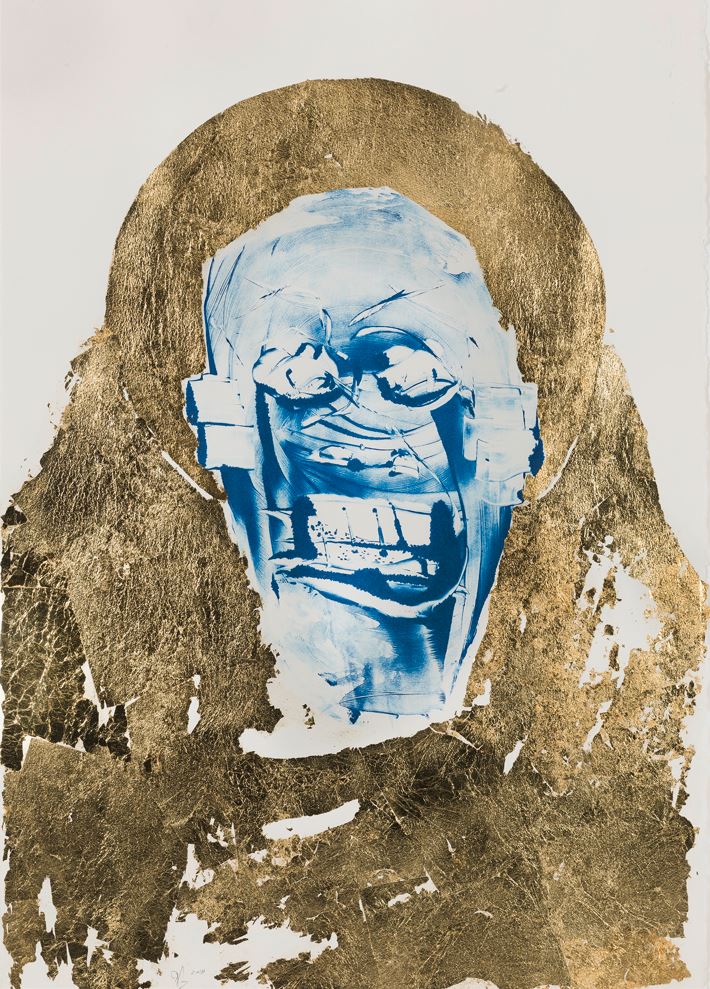

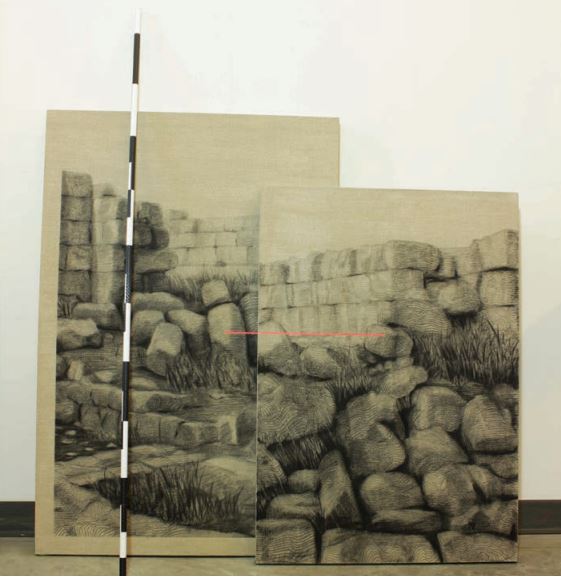

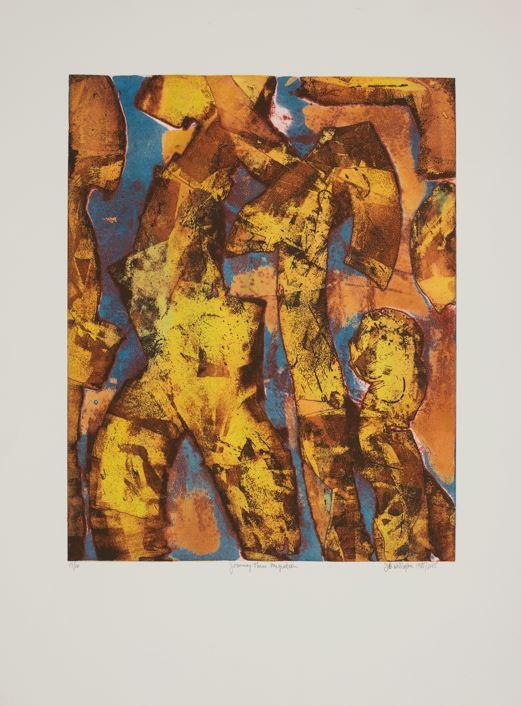

My top priority at present is to bring the love, passion, and energy I have for art and for serving communities through museum work to my new role. How this will take shape, I can’t be sure. I must begin with understanding what the Phillips is now, where it came from, and how it got here. The current exhibition, Pour, Tear, Carve, featuring a broad selection of works from the permanent collection, is a timely opportunity to get to know some recent acquisitions. We owe a lot to Director Emerita Dorothy Kosinski and her 15-year tenure, including for leading the effort to expand the size and scope of the permanent collection. I’m familiar with the historical treasures, but the Phillips is much more than that today.

Programmatically, we are firing on all pistons. We engage guests at 21st Street, THEARC in Southeast DC, and online with a wide variety of offerings. These include in-person events, hands-on art-making sessions, weekly online meditations on art, teacher professional development, pre-K–12 programs, and our Phillips Music series . . . the list goes on. Moreover, I want to get to know the more than 100+ full-time team members, if only on a first-name basis—this will be tough given that I’m good with faces but not so much with names! And I must develop a productive conversation with every member of the Board of Trustees, each of whom has impressed me in these early weeks with their dedication and hard work on behalf of the museum. Ours is very much a working board, and this engaged leadership is instrumental to what makes the Phillips such a special, successful, and beloved institution. Suffice it to say I have a lot of learning to do.

Jonathan P. Binstock chats with visitors at the opening of Pour, Tear, Carve. Photo: Ryan Maxwell.

What do you hope for the Phillips’s second century?

In a nutshell, my hope is to build on the success, for the Phillips is a uniquely successful institution. Yes, for its incredible art collection and excellent, dynamic programming, but also for something else, something even more difficult to describe than a Post-Impressionist treasure, or the feeling of time spent inside the Rothko Room. I’m beginning to believe there are two kinds of people in the world: those who have never visited, and those for whom the Phillips is their (or one of their) favorite art museums. There is something undeniably special about the place. It manifests a magical brew—of exceptional art, intimate, domestically scaled architecture, tree-lined neighborhood streets, and idiosyncratic founding principles derived from the DNA of a welcoming familial vibe—that creates the right conditions for people to fall in love with what we have and are. My very first hope is to further this sentiment. Let’s build strength on strength. How can we cultivate more love?

Will there be change? To be sure. To know the story of Duncan Phillips is to know how our founder was always curious and open-minded, eager to learn and expand his taste; he was always evolving, both as a collector and an institutional leader. The Phillips may be more than 100 years old, but I see it as still in its adolescence. The Phillips is precocious, ambitious, and has always punched above its weight and scale. Where will our open-minded curiosity lead us? For the Phillips, the best is always yet to come.

How will you ensure that diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion (DEAI) continues to be infused in all of The Phillips Collection’s work?

The Phillips was one of the first art museums to engage a Chief Diversity Officer, and the work that the staff and trustees have been doing regarding DEAI has touched nearly every aspect of the museum. Before I became director, I could see the institution’s DEAI principles in its exhibitions and programs. Now that I’m here, I look forward to working closely with Dr. Yuma Tomes, our Horning Chair for Diversity, Equity, Access, and Inclusion, to embed those principles more deeply into who we are and what we do, and to see every aspect of the institution through a DEAI lens. Ensuring that anyone who’s interested feels they belong at the Phillips and as if the Phillips belongs to them is not just the right thing to do. This is a key strategy for increasing the love, and it will help ensure the strength of our museum for the future. Part of what attracted me to the Phillips was the opportunity to have a permanent DEAI professional on staff, because doing this work well demands that the necessary expertise be at the leadership table all the time. My role is to make sure all of us—staff, board, and volunteers—understand our responsibility for advancing equitable and inclusive strategies and practices in every corner of the institution. Dr. Tomes leads this effort, and I will make sure he has the resources to do so.

What is your favorite Phillips artwork?

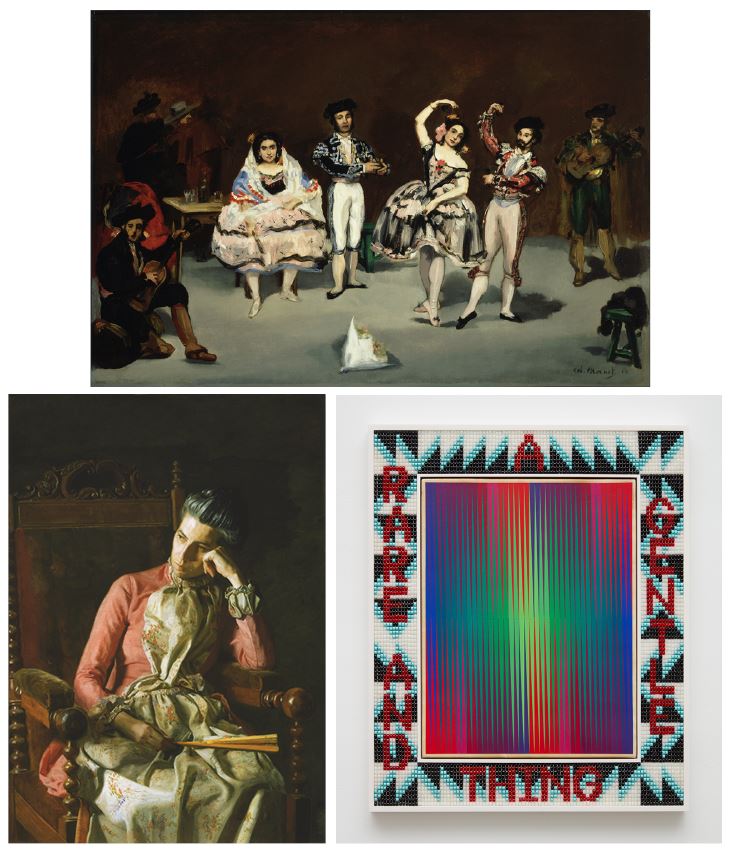

This is an unfair question. I was told being the Vradenburg Director and CEO would be a challenging role, but no one said it would be this challenging! Okay, all kidding aside, if I may be allowed to have several favorites, and if we may limit the discussion to what’s currently on view, then I will indulge the impossibility of the task. Miss Amelia Van Buren by Thomas Eakins is as remarkable a depiction of pensive absorption as there has ever been, and it is arguably by the greatest American realist whose paintings are terribly rare. Granted, its traditionalism makes it a bit of an outlier in the collection. That being said, having spent two years in Philadelphia, where Eakins lived and worked, his art holds a special place in my heart and I am thrilled that we have one of his best paintings in our collection.

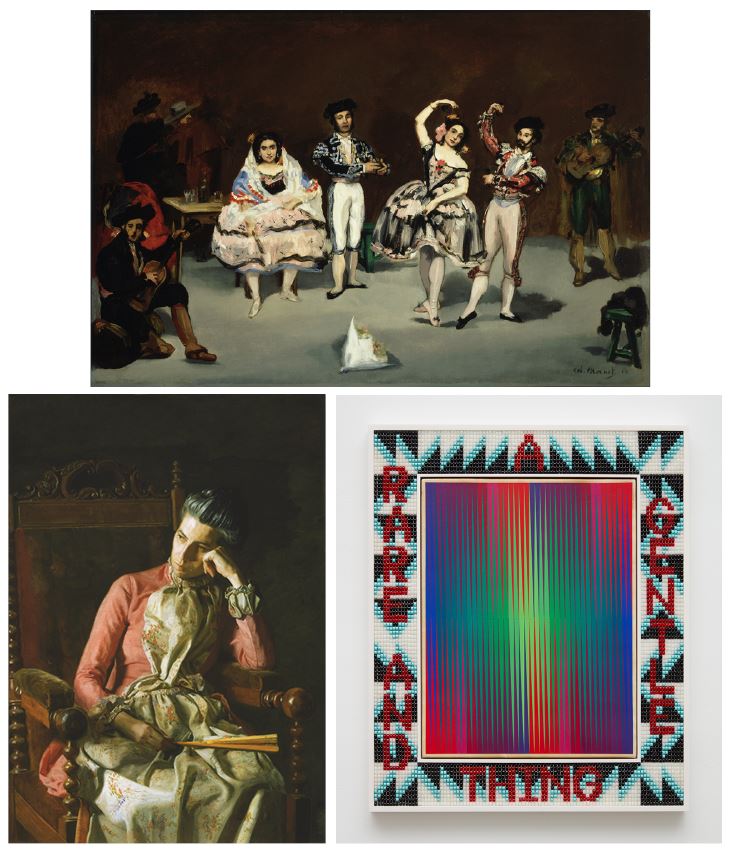

One can’t talk about Eakins without talking about Diego Velázquez and the Golden Age of Spanish painting—one of modernism’s sources, as understood by Duncan Phillips—which leads me to another Phillips jewel, Spanish Ballet by Édouard Manet. Manet manifested his admiration for the Spanish realist tradition in profoundly more radical terms than Eakins, which brings this discussion closer to the experimental heart of the Phillips project.

Thomas Eakins, Miss Amelia Van Buren, c. 1891, Oil on canvas, 45 x 32 in., Acquired 1927; Edouard Manet, Spanish Ballet, 1862, Oil on canvas, 24 x 35 5/8 in., Acquired 1928; Jeffrey Gibson, A RARE AND GENTLE THING, 2020, Acrylic on deer hide on panel, glass beads and artificial sinew inset into wood frame, 34 1/2 x 28 7/8 in., Promised gift of Lindsay and Henry Ellenbogen in loving memory of Mirella Levinas, © Jeffrey Gibson

Finally, I absolutely adore Jeffrey Gibson’s A RARE AND GENTLE THING. Gibson, a member of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, painted this strikingly beautiful and very sweet work on deer skin, an homage to Native American materials and traditions. Equally touching is its credit line, which is a promised gift to the Phillips from Lindsay and Henry Ellenbogen in loving memory of Mirella Levinas, the late wife of our Chair Emeritus, Dani Levinas, making it doubly moving as a work of art. I am inspired by how the Phillips can be a place—a home—for contemplating people, lives, and ways of living and thinking from the past, and also play a role in enriching how we see ourselves today.

What is your favorite DC spot?

The 9:30 Club, and if you run into me there, I apologize in advance for my un-director-like behavior.