Artist Lisa Rosenstein of the Otis Street Arts Project reflects on the hands-on workshop she led: The Head as a Vessel.

When the pandemic began in March of 2020 it was as if I’d tripped and fallen down the stairs into a very, very dark hole. Never mind that my home is filled with light and I want for nothing, I was even fortunate enough to have the company of my daughter who’d moved home temporarily. Still, I felt helpless and that perceived lack of control led to a time of darkness and reflection while solidifying my belief that we are all part of one big seething organism. It was a shocking and disorienting time to be without access to my studio and my practice of non-verbal processing.

Once the shock wore off, I came to realize that being sequestered in a sheltered space with few distractions created an environment of vast possibilities. One possibility presented itself to me on a Sunday as I was reading the newspaper (hard copy, believe it or not!). The articles and accompanying images were deeply distressing as usual. I read on, my reaction turning from grief to anger to physically tearing the paper, crushing, squeezing, and twisting it until suddenly I was holding a misshapen bowl.

First bowl, April 2020. Photo by Lisa Rosenstein

Holding that physical object in my hands opened me up and I felt a subtle lifting of my spirit.

From that moment on and for the next six months I continued the bowl making process, even incorporating some older newspaper articles (having always been a collector of words and images). It was my way of being present in this moment of history that included the pandemic, the continuing horror of police brutality toward people of color, and of course our destructively dysfunctional governmental head. The bowls proliferated filling every surface of my home like a field of emotional mushrooms. At least until my daughter suggested I just pile them up one inside the other. This daily ritual became a time of integration, my awareness expanded even as my physical space had contracted.

Bowls Grow Like Mushrooms, April 2020-October 2020. Photo by Lisa Rosenstein

The process of making the bowls is uncomplicated:

- Read the newspaper until an image or a set of words sets off an emotion or deeper thought.

- Get a plastic mixing bowl, any size. I prefer the smaller ones; they are more intimate.

- press the newspaper into the bowl and add water, continue pressing until you have an image you like. finish the edges as you please. squeeze out excess water.

- Place the finished bowl into a sunny spot or near a heating vent in your home.

- Once the bowl is dry remove it from its mold

- The bowl is complete and will hold its shape though it has no binders and will eventually decay.

The simplicity of the process was perfect and I was thankful to have a meaningful idea ready for the Phillips Hands On Workshop program.

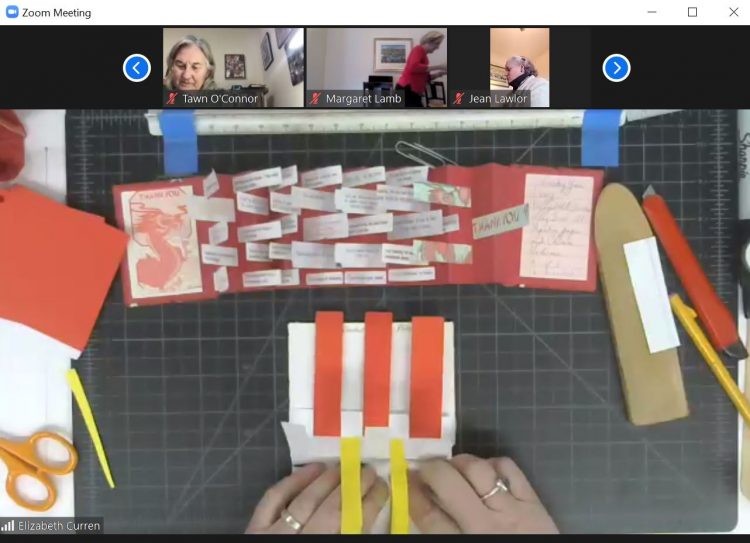

Making bowls during the online workshop

The Head as a Vessel workshop emphasized our minds as places of introspection, change, and growth and it was my intention that the Zoom workshop be a symbolic safe space for the participants to share their thoughts and feelings through the act of art-making.

I led the participants in the making of four bowls. The final two bowls were the most meaningful. The first, what I called the pandemic bowl, was focused on what the participants had been living through and feeling since the pandemic had begun. The other I named the future bowl and asked the participants to think about what they wanted for the future. I had two pre-made bowls at hand and invited people to call out words pertaining to each topic. I inscribed these words into the appropriate bowl. Once this exercise was complete, I filled the future bowl with soil and crocus bulbs. As a finale the pandemic bowl was set on fire and burned to ash. It was a satisfying and cathartic moment.

We are all living through a complex historic time. Humanity is a collective organism and what each one of us does affects the other in a never-ending circle. We can choose to stay in the dark or grow to the light.

In February 2021 the bowl of the future blossomed.

Bowl of the future, February 2021. Photo by Lisa Rosenstein