This month marks the 51st anniversary of Pride, a celebration of the LGBTQ+ community that is only possible because of the Queer POC who rebelled against oppression, discrimination, and police brutality. We are sharing some of the work, voices, and ideas of the LGBTQ+ artists in our collection. It is with reverence to the Black activists that paved the way for LGBTQ+ rights that we reflect on art as activism and an agent for change.

Lyle Ashton-Harris, Blow-Up II (Armory), 2005, Digital c-print, 24 x 20 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of Carolyn Alper, 2010

Lyle Ashton Harris is multimedia artist working in photography, collage, installation, and performance art. His work often explores the theme of identity—specifically how gender, sexuality, and history are tied to Black and Queer identities. The artist began a series of collages in the mid-1990s, which use transparency, layering, and fragmented images to connect the disparate elements that form a person’s identity. The quote is from Harris’s artist statement from when he was an MFA student. Art historian Deborah Willis once described his work’s importance “on being visible, and not necessarily where people talk about hyper-visibility. It’s about staying present and using the archive to code and decode Black stories. That’s been an essential frame for him. That’s why his work has an impact. He’s in your face with it.”

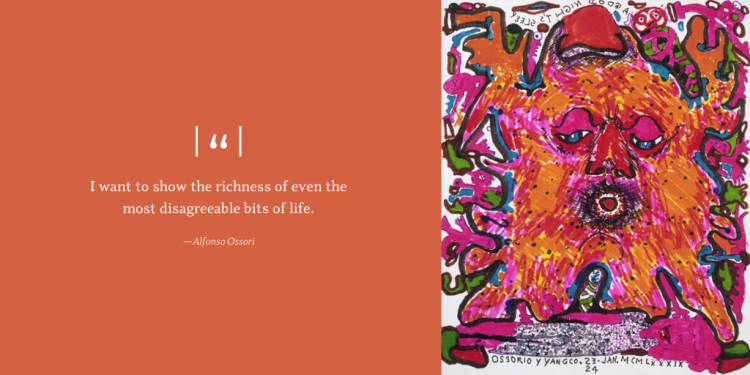

Alfonso Ossorio, Recovery Drawings #6 (A Good Night’s Sleep), Book 1, 1989, Felt-tip watercolor marker on paper, 8 1/2 x 11 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of the Ossorio Foundation, 2008

Alfonso Ossorio was one of the most colorful figures in postwar American Art. Following his work as a medical illustrator during World War II, Ossorio went to the Berkshires where he began exploring surrealist painting. It was there that he met his partner, ballet dancer Ted Dragon, while he was sketching flowers at an outdoor festival. The two remained together until Ossorio died in 1990. While his roots were in surrealism, Ossorio was drawn to the anarchic, cathartic, and rebellious style of artists Jackson Pollock and Jean Dubuffet—their friendship was explored in the Phillips’s 2013 exhibition Angels, Demons, and Savages: Pollock, Ossorio, Dubuffet.

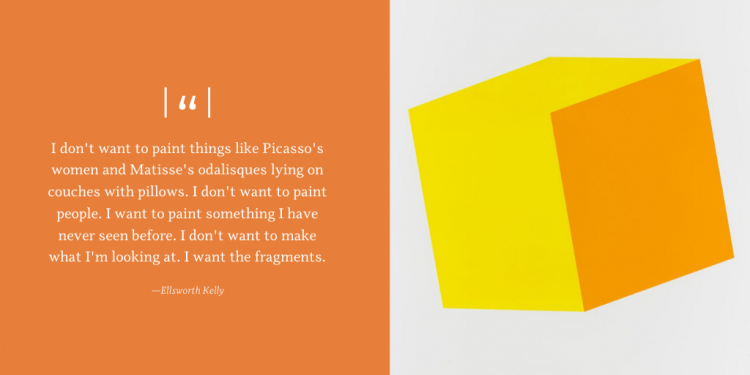

Ellsworth Kelly, Yellow/Orange, 1970, 2-color lithograph on Arjomari paper, 41 1/2 x 30 1/4 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of Fenner Milton, 2013

At first glance, the hard edge paintings of Ellsworth Kelly seem more similar to the work of pop artists or minimalists than the work of his contemporaries like Picasso or Rothko. But Kelly missed Abstract Expressionism almost entirely, as he was serving as a camouflage expert in Paris during and after the second World War. It was during that time that he was exposed to the work of modern artists that would influence his exploration of color and form. It is possibly because of this—his exposure without assimilation to any one movement—that Kelly developed work that was so unusual for his time.

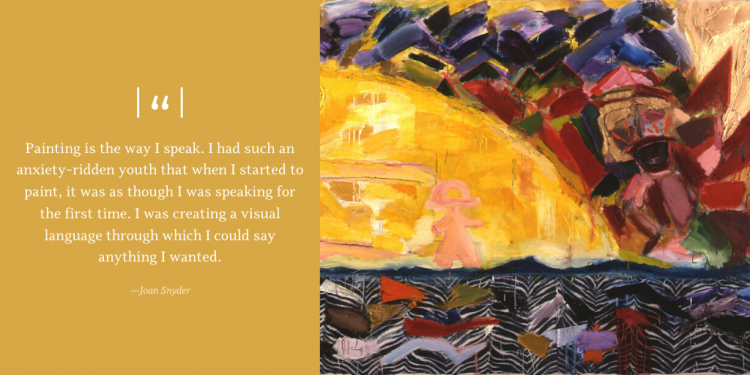

Joan Snyder, Savage Dreams, between 1981 and 1982, Oil and fabric on canvas, 66 x 180 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Gifford Phillips in honor of Laughlin Phillips, 1992

Joan Snyder’s work incorporated non-art materials, often associated with domesticity, to create confessional, personal works of art. When Snyder was making work in the 1960s, there was a greater artistic concern for process; she considered the application of her materials to be a ritual that further pushed the intent of her pieces.

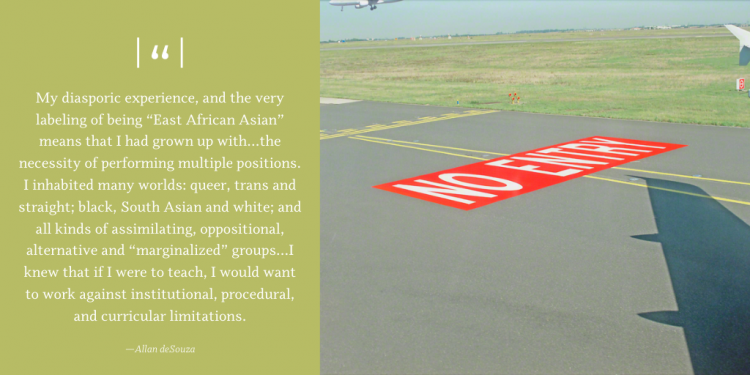

Allan deSouza, No Entry, 2011, C-print, 12 x 16 in., The Phillips Collection, Purchase, The Hereward Lester Cooke Memorial Fund, 2014

This photograph by Allan deSouza was made in response to Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series as part of Intersections, a series of contemporary art projects inspired by the art and spaces of the Phillips. The Migration Series tracks a journey and a movement toward a better life. Allan deSouza focused on that narrative and his own history of migration—his family’s move from South Asia to Kenya, and his journey from Kenya, to England, to the United States—creating a series of photographs that explore themes of diaspora and colonization. The World Series was shown at the Phillips in 2011.

The quote is from deSouza’s How Art Can Be Thought: A Handbook for Change, strategies he has developed as an artist and educator on how to decolonize museums and academic spaces.

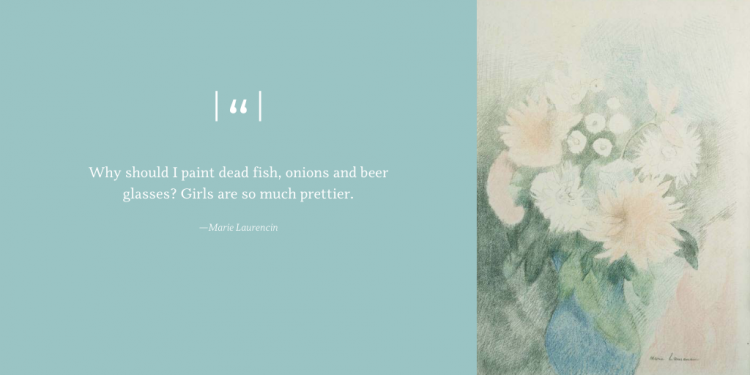

Marie Laurencin, Flowers, not dated, Lithograph on paper, 14 5/8 x 10 3/4 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of Marjorie Phillips, 1985

Marie Laurencin, one of the few female Cubist painters, pushed beyond the norms of that movement by introducing curved lines, pastel colors, and other artistic elements that were often dismissed as too feminine. Laurencin frequently had her work shown at Gertrude Stein’s salons and was very active in the emerging gay and lesbian scene in 1920s Paris. During this time Laurencin began referencing neoclassic and sapphic imagery in her work and those themes eventually became the entirety of her practice.

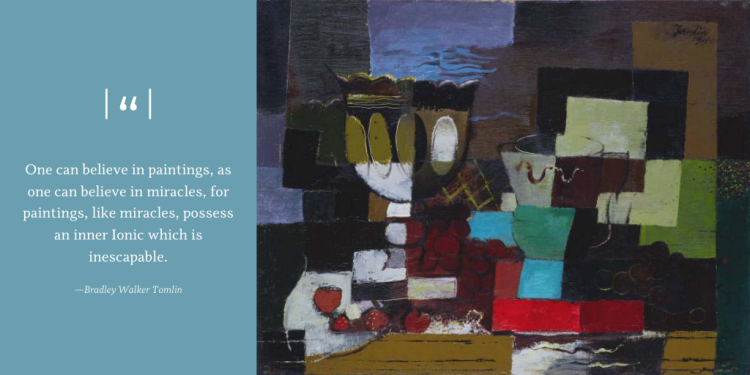

Bradley Walker Tomlin, Still Life, 1940, Oil on canvas, 22 1/8 x 29 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1944

Bradley Walker Tomlin straddled two different waves of American artists—he began working as an illustrator at the same time that Edward Hopper, Charles Burchfield, and other representational artists were at the height of their careers. Only five years later, the New York School and action painting took center stage. While Tomlin’s style evolved during this time, his work was often described as gentle, reserved, and unobtrusive. The Abstract Expressionist movement formed its identity around masculinity and bravado, and was never fully accepting of women, Black artists, or any perceived “outsiders.” Hedda Sterne, one of the few women involved with this group once said, “They all were very furious that I was in it because they all were sufficiently macho to think that the presence of a woman took away from the seriousness of it all.” Tomlin was unacknowledged as gay during his lifetime; it wasn’t until his long overdue retrospective in 2017 that his work was viewed within the context of his sexuality.

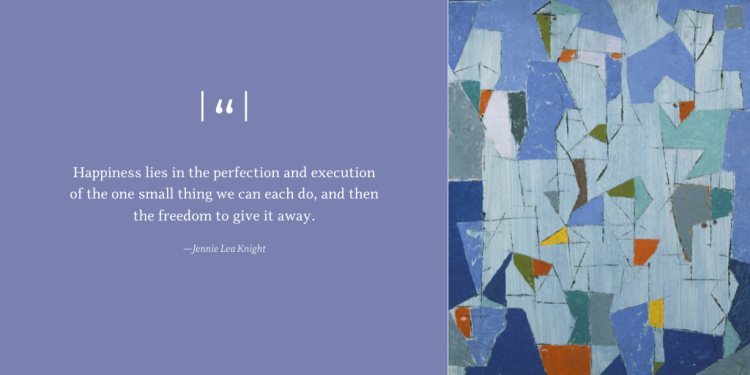

Jennie Lea Knight, Bluescape, 1950, Oil on hardboard, 20 x 16 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1951

Abstract painter and sculptor Jennie Lea Knight changed the DMV art scene in the 1960s. After studying under Kenneth Noland, Knight co-founded Northern Virginia’s first and only professional art gallery. She directed the gallery for 10 years before giving ownership to the participating artists, making it the city’s first cooperative. While her work was largely non-representational, Knight was influenced by forms found in nature. In addition to working as a full time artist, she was also a certified wildlife rehabilitator who lived on a working farm with her partner.

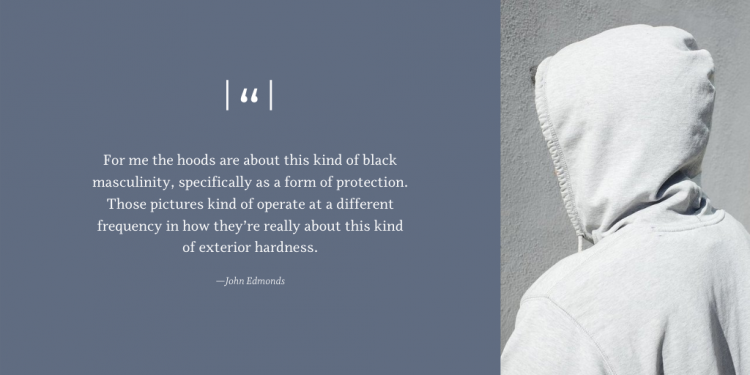

John Edmonds, Untitled (Hood 2) (detail), 2016, Archival pigment print, 20 x 14 in., The Phillips Collection, Promised gift of Vittorio Gallo, 2018

In 2019, Chief Diversity Officer Makeba Clay spoke with artist John Edmonds during a Conversations with Artists event about his Hood series, which he began as an MFA student at Yale. The series confronts the toxicity of racial bias, while exploring themes of privacy, vulnerability, and protection.

Makeba Clay: So the hood is complex, it’s a complex symbol that is having us…thinking about the politicization of the Black male body, the policing of the male Black body as well, and also thinking about the softness and the beauty of the way that it is framed in your photographs.

John Edmonds: For me the hoods are about this kind of Black masculinity, specifically as a form of protection. Those pictures kind of operate at a different frequency in how they’re really about this kind of exterior hardness.

Here’s to visibility, Black stories, and making an impact!