Head of PK12 Initiatives Erica Harper explores works by Barbara Hepworth, Regina Pilawuk Wilson, and Angela Bulloch.

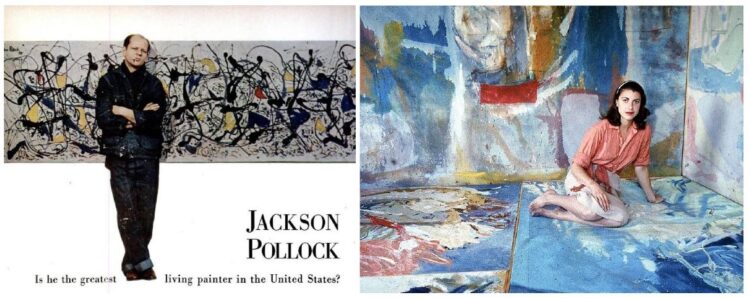

The lede for Jackson Pollock’s 1949 LIFE magazine article reads: “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” Pollock is photographed in (an admittedly bad-ass) paint spattered leather jacket and jeans combo, his clothing a canvas against another canvas of his own. His stance is cool and casual, leaned back with his arms folded across his chest. His face is stoic, punctuated by the cigarette dangling from his mouth. The message seems clear—abstract expressionism is tough, complicated, and undeniably masculine.

(Left) Jackson Pollock in LIFE magazine; (Right) Helen Frankenthaler in LIFE magazine

By the time Helen Frankenthaler is photographed by Gordon Parks for her own spread in LIFE in 1956, her influence on the art form is undeniable. Parks photographed her barefoot, wearing a knee-length skirt and button-down shirt tied into a side knot, surrounded by her works. She sits, quite literally, as a stark contrast to Pollock (photographed by Martha Holmes). But Frankenthaler, much like many artists at the time who happened to be women, balked at the categorization of “woman artist.” She once said in the New York Times, “There are three subjects I don’t like discussing: my former marriage, women artists, and what I think of my contemporaries.”

So what, right? Perhaps Pollock was truly the greatest living painter in the United States in 1949, but who was even included in that conversation? What then of all the aspiring artists who didn’t fit the mold? I’d like to turn your attention to some great works in our collection which all happen to be outdoors, and all happen to be by women. I started to wonder if those women, like Frankenthaler, felt dismissive of the label or if perhaps “woman artist” meant something different?

Barbara Hepworth (born 1903, Yorkshire, England) was 46 years old when Pollock graced LIFE magazine. Her sculptures can be interpreted as being about relationships: between forms, between humans and landscapes, color and texture, and especially between people as both individuals and a part of society. Hepworth was truly a force in her time, a major international figure, showing her work in exhibitions all over the world. She took an active role in the way her work was presented and was particular about its documentation. That she was a woman in a largely male-dominated world did little to stop her.

Barbara Hepworth, Dual Form, 1965/cast 1966, Bronze height: 72 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired with the Dreier Fund for Acquisitions and additional funds from Natalie R. Abrams, Alan and Irene Wurtzel, and a bequest from Nathan and Jeanette Miller, 2006

Master weaver Regina Pilawuk Wilson (born 1948, Northern Territory of Australia) was one-year old at the time of Pollock’s cover. Her subject matter is based around weaving fiber art using techniques she learned from her grandmother who taught her where, when, and how to collect the right grasses, vines, and sources of natural color like flowers, berries, and roots. She perfected them over the decades and became an authority figure for her sense of familial and cultural identity. Most known for her paintings, printmaking and woven fiber-artworks, she paints syaws (fish nets), warrgarri (dilly bag), and yerrdagarri (message sticks). Her work has been shown in many Australian and international museums, collections, and galleries. Wilson’s work is markedly ancestral and matrilineal in origin, and divorcing it from “woman” feels almost sacrilege from my vantage.

Regina Pilawuk Wilson painting Yerrdagarri in the Hunter Courtyard, 2018. Photo: Rhiannon Newman

Finally, there’s Angela Bulloch (born 1966, Ontario, Canada). She wasn’t even alive when Pollock appeared on the cover of LIFE. The world had changed so rapidly, and in so many ways that it’s no surprise that Bulloch’s work incorporates video, sound, light, installation, sculpture, and painting. In fact, her work that sits outside the museum was partly created with the use of a computer program. She is also part of the Young British Artists, a loose group of visual artists who first began to exhibit together in London in 1988. And, despite the cultural advances of the time, female artists were still a distinct minority among the male dominated environment of the Young British Artists.

Angela Bulloch with her sculpture. Heavy Metal Stack: Fat Cyan Three, 2018, Powder coated steel, Made possible with support from Susan and Dixon Butler, Nancy and Charles Clarvit, John and Gina Despres, A. Fenner Milton, Eric Richter, Harvey M. Ross, George Vradenburg and The Vradenburg Foundation. Photo: Rhiannon Newman

I lament that I don’t actually know how these women would feel about being called a “woman artist.” I can imply but that feels wholly irresponsible and arrogant to do. But then I came across a quote from Hepworth that addressed this very subject. She gave birth to triplets in 1934, and, atypically, found a way to both take care of her children and continue producing her art. And though she likely wouldn’t want to speak for women as a whole, I’ll leave you with her words to consider:

“A woman artist is not deprived by cooking and having children, nor by nursing children with measles (even in triplicate)—one is in fact nourished by this rich life, provided one always does some work each day; even a single half hour, so that the images grow in one’s mind.”

References:

Frankenthaler: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/10/08/how-new-yorks-postwar-female-painters-battled-for-recognition

Hepworth: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/dame-barbara-hepworth-1274/who-is-barbara-hepworth

Pollock: https://www.life.com/people/jackson-pollock-early-photos-of-the-action-painter-at-work/

Bulloch: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angela_Bulloch

Wilson: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regina_Pilawuk_Wilson