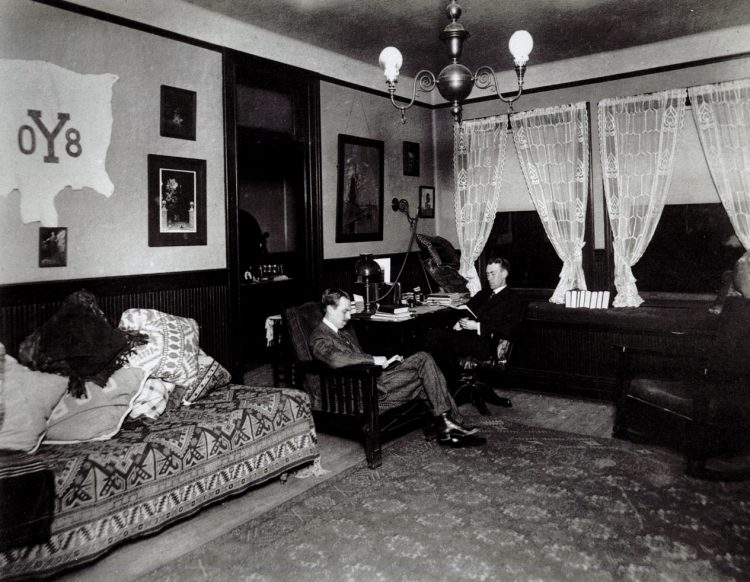

When Duncan Phillips arrived at Yale University in 1904, he was interested in pursuing English and writing. He wrote about art during his time there, but was disappointed at the absence of an art curriculum; Yale had dropped its only art history course due to a lack of student interest. After visits to the Met in New York, Duncan penned the essay “The Need of Art at Yale,” which issued “a reasoned plea for the creation of a course in art history that would prepare students” for enjoyment of the world (George Heard Hamilton, The Eye of Duncan Phillips: A Collection in the Making).

Duncan Phillips’s views on arts education are as relevant as ever. His essay reads, “A wider diffusion of artistic knowledge and instinct would give birth and guidance to dormant individualities of taste, and would not only increase the number of future artists and art critics, but would help to color the lives of the future citizens of the republic, and thus advance the precious cause of the beautiful, in this marvelous breathless modern world.” With this, Duncan put art as a prerequisite to experiencing humanity and served as an early advocate for arts education.

Maya Simkin, Library Intern