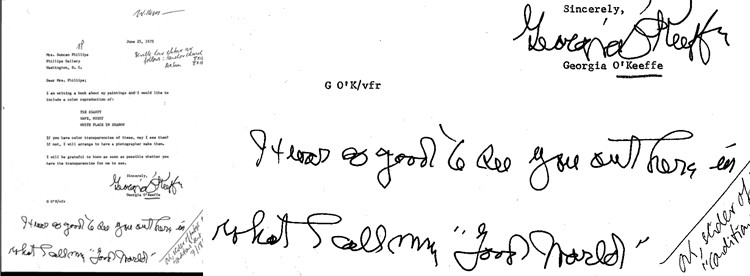

CityDance artist Sarah J. Ewing guest blogs about her upcoming Georgia O’Keeffe-inspired performance at the Phillips on May 12.

Through the process of making Analog O’Keeffe with the CityDance Conservatory Dancers, I have kept coming back to the word “audacity,” and more specifically: the audacity of choice. That word and that drive has been the starting point of the choreography, and is what attracts me to Georgia O’Keeffe’s work. I am not particularly rebellious in my life or in my work, but I do aim to be audacious.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Pattern of Leaves, 1923. Oil on canvas, 22 1/8 x 18 1/8 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC. Acquired 1926 © 2008 The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The creation of contemporary dance is a constant decision making process, and one that really doesn’t carry a rule book of what is right or wrong. You have to walk bravely into the unknown when you make a new work and never let the fear or uncertainty of that process hold you back. To have the audacity to create what you want to see in the world—I hope that the young dancers in this piece walk away from this process with a taste of just how powerful of a notion that is.

I also love computer code, the automation of workflows and the beautiful logic that runs databases and websites. It is everything that dance isn’t; reliable, consistent, and permanent—and yet, for me, the process of creating a dance piece and designing a database are the same. The goal is to hold as much information as possible inside a structured design so that the audience, or the end user, can obtain the information that they need to access.

Choreography is made rich by the use and manipulation of time, space, and energy. In a database, these elements would be the tables that hold records which individually don’t say much, but when put with other records, can tell the history of one dancer’s training for the past 10 years. You can see that training when you watch them perform through their skill and technique, or you can pull a report from the database and make a pivot table. We all like to receive information in different ways; for this project I chose to combine my two favorite ways into one.

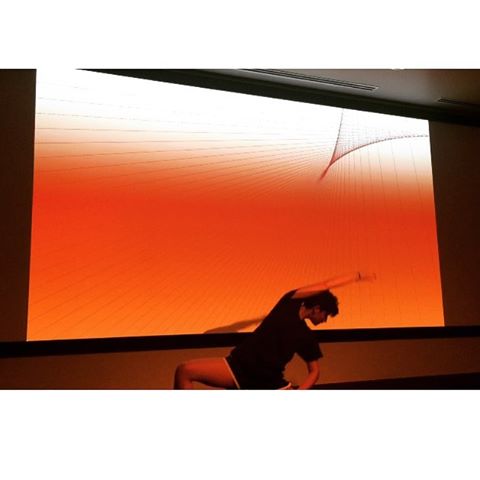

We are using Xbox Kinect sensors to track the dancers movements, and then using this data to manipulate my animations that are programmed in Quartz Composer. These will be projected during the performance, allowing the dancers to create the entire environment of their performance based on their own choices in movement. That brings us back to audacity—and the power that free choice gives us. I hope the audience sees a little O’Keeffe in the show, and also a little of the students themselves—both inspire me every day.

Sarah J. Ewing, CityDance Ignite artist