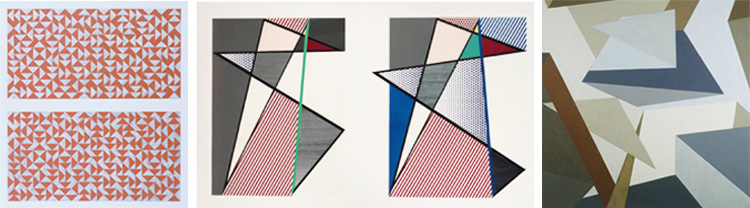

Anni Albers, Fox I, 1972. Photo-offset litho on paper, 24 x 20 in. Gift of Katherine and Nicholas Fox Weber, 1981; © 2008 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Roy Lichtenstein, Imperfect Diptych (Imperfect series), 1988. Woodcut, screen print, and collage on museum board, 57 7/8 in x 97 3/4 in. Gift of Sidney Stolz and David Hatfield, 2009; Frank Keller, Specter Planes VIII, 1980. Oil on wood panel, 41 x 41 in. Gift of Arthur E. Smith, 1980

To me, one of the greatest things about museums is their ability to create interesting juxtapositions that allow viewers to see things they may not have seen otherwise. In a gallery located in the original Phillips house, three striking works are put into conversation with one another: Anni Albers’ Fox I, Roy Lichtenstein’s Imperfect Diptych, and Frank Keller’s Specter Planes VIII. Each composition employs geometric shapes, notably triangles, to very different effects. They provide three distinct visions, demonstrating how similar subject matter can be presented in more than one way.

Anni Albers’ Fox I (1972) consists of two horizontal, patterned rectangles, separated by a wide gap. On the top, gray triangles facing in various directions are arranged in front of a red background. The bottom is an inversion of this, placing red triangles over a background of gray. The shapes are uniform in size and evenly spaced. The precision and carefully crafted geometry of this work speaks to Albers’ long career as an accomplished textile designer and weaver. The print is planned and systematic, confined within rigid parameters. Yet, there is a freedom from complete uniformity. Facing in different directions, the triangles add a dynamic element and bring vitality to the work.

Measuring 57 7/8 x 97 3/4 inches, Imperfect Diptych (1988) by Roy Lichtenstein occupies an entire gallery wall. Like Albers, Lichtenstein divides the composition into two rectangles. He depicts various geometric shapes, coloring them with matte gray, shiny silver, splashes of red and blue stripes, and of course, red and blue versions of the famous Benday dot pattern. Remember when you were in elementary school and learned how to draw a star without picking your pencil up off of the paper? This print reminds me of that technique in that the shapes seem to all stem from the same line. This composition is not as restricted as the Albers; we can see Lichtenstein starting to experiment with the idea of both preserving the shape’s geometric order, and wanting to break free from it.

Frank Keller’s Specter Planes VIII (1980) depicts various shapes that lack a coherent spatial arrangement. No two shapes are identical, though Keller does repeat some muted colors. Because it is a painting rather than a print, the artist’s hand is much more evident in this work than in the others. He employs strong diagonals to create the illusion of space, creating a depth that the Albers and Lichtenstein lack. Of the three artists, Keller breaks free from order the most. Some shapes overlap, obscuring parts of others, and some float away from the center, travelling out past the confines of the composition.

Fox I, Imperfect Diptych, and Specter Planes VIII’s current installation in the gallery together not only shows various ways to deal with geometry, but provides a rich viewing experience. From the highly ordered composition by Albers, to the work starting to break free from its confines by Lichtenstein, to the freedom of Keller’s canvas, the order and disorder of each piece is emphasized in its comparison to these gallery companions.

Emily Conforto, Marketing & Communications Intern