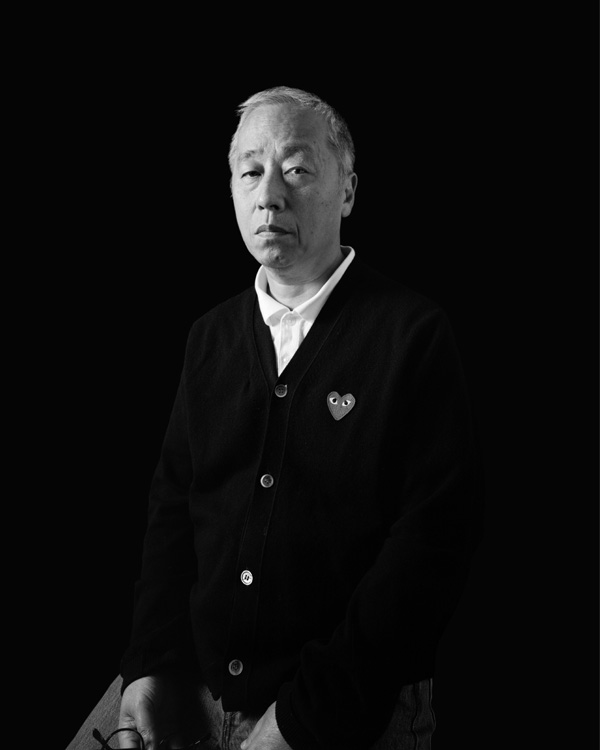

Gerry Hendershot volunteering at the Phillips. Photo: Emily Bray

Gerry Hendershot is an Art Information Volunteer at The Phillips Collection. Here he shares his process and his poem inspired by Edward Hopper’s painting, Sunday.

In February I attended a three-day poetry workshop near Atlantic City, NJ. Each morning, 100 student poets gathered to receive a one-sheet prompt, then were given two hours to draft a poem; in the afternoon, groups of ten student met for moderated discussions of each poem.

On the day I wrote the below poem, the morning prompt directed us to write about something that was missing using stanzas of 2, 3, or 4 lines, and to include a piece of furniture, a spice, a proper name, and a musical instrument. We had to submit a hand-written fair copy of 30 lines by Noon.

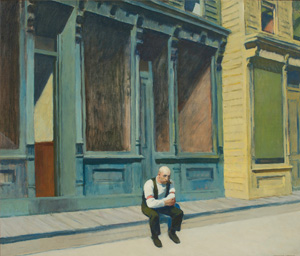

Because of my longtime love of art, I have acquired an interest in ekphrastic poems; that is, poems about art, such as W. H. Auden’s “Musée des Beaux Arts.” I recalled a poem by Victoria Chang, “Edward Hopper Study: Hotel Room,” which led me to think of Hopper’s painting Sunday.

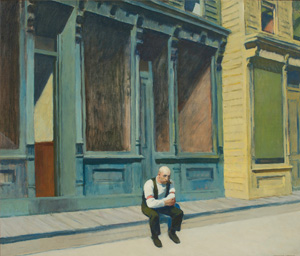

I had recently attended a Spotlight Talk on Sunday, where I heard other viewers comment on its unsettling psychological impact. Like other works by Hopper, it creates in me a feeling of imminent danger, of something tragically missing.

With Chang’s exemplar as guide, and Sunday in my mind’s eye (aided by online images!), it was not difficult to meet the other prompt requirements— proper name, furniture, spice, and a musical instrument. Feedback from fellow student poets led to revisions—which are continuing.

Edward Hopper, Sunday, 1926. Oil on canvas, 29 x 34 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1926

Edward Hopper, “Sunday” (1926)

By Gerry Hendershot

After church, when I view him sitting

on the curb of an old-fashioned

wood plank sidewalk,

leaning forward, resting his arms on his knees,

cigar clamped in his teeth, its tip unlit,

its cold ragged head soggy with spit,

he’s gazing into the distance, eyes unfocused and blank,

sensing—not knowing—that something,

something is missing.

***

Bright sun beats the top of his balding head,

whitening one side of his face,

leaving the other side dark.

He’s wearing his work clothes, his not-Sunday-best clothes,

the sleeves of his white shirt held up by elastic red bands;

black vest, black pants, brown shoes. A waiter, perhaps,

or a barber. But the storefronts behind him are missing

any ads for today’s blue-plate specials, and a

red and white candy striped pole.

***

Is he missing the tools of his trade?

His revolving, adjustable, strop-hung chair? His shelf

full of brushes and scents, precursors of Boss and Old Spice?

Or does he miss in that sharp angled light from above

a rainbow of hope sung by angels with lyres

through windows of medieval glass?

Sunday, what’s missing

from his life

and mine?

Gerry Hendershot is a retired CDC health statistician who has been volunteering at the Phillips for 12 years. He is a member of the nearby Church of the Pilgrims at 22nd and P Streets, NW, and co-founder, with his wife, of its Dupont-Pilgrims Art Gallery, an alternative art space for area artists.