Deputy Director for Education and Responsive Learning Spaces Anne Taylor Brittingham shares her experience at the Education Integration (EDI) Global Forum in Naples, Italy

From October 12-14, Donna Jonte, Head of Experiential Learning, and I were able to attend the inaugural convening of the EDI (Education Integration) Global Forum. The EDI Global Forum seeks to inspire change, promote sustainability, connect communities, spark innovation, and rethink education. The three-day conference in Naples, Italy, brought together 200 museum professionals representing 180 institutions actively working with education through the lens of art and culture. After years of isolation, it was amazing to be at a conference with people from 5 continents, 80 international institutions, and 100 Italian organizations. Through a series of keynote lectures, participatory workshops, and collaborative working groups, the convening focused on five themes: Accessibility, Diversity and Inclusion, Sustainability, Art and Well-Being, and Institutional Structure.

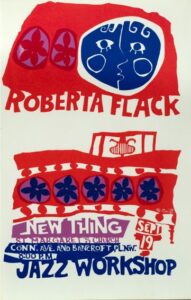

EDI Global Forum participants at National Archaeological Museum

I moderated a session with the Pinacoteca in São Paolo, Brazil, and the MANN (National Archaeological Museum) in Naples. The session brought together perspectives from Naples and San Paolo to address how to engage communities that museums are not always prepared to welcome, including sex workers, the homeless, and youth without access to cultural institutions. As a part of the workshop, we performed a “SWOT” analysis of the strengths, weakness, opportunities, and threats to engaging a group at risk of social exclusion. Museum professionals from London, Switzerland, Germany, Brazil, Italy, and the United States discussed how we can not only reach these traditionally excluded audiences, but also how to prepare staff to welcome all guests to the museum.

Anne Taylor Brittingham, The Phillips Collection; Gabriela Aidar, Pinacoteca Sao Paolo; Angela Vocciante and Elisa Napolitano, MANN Naples

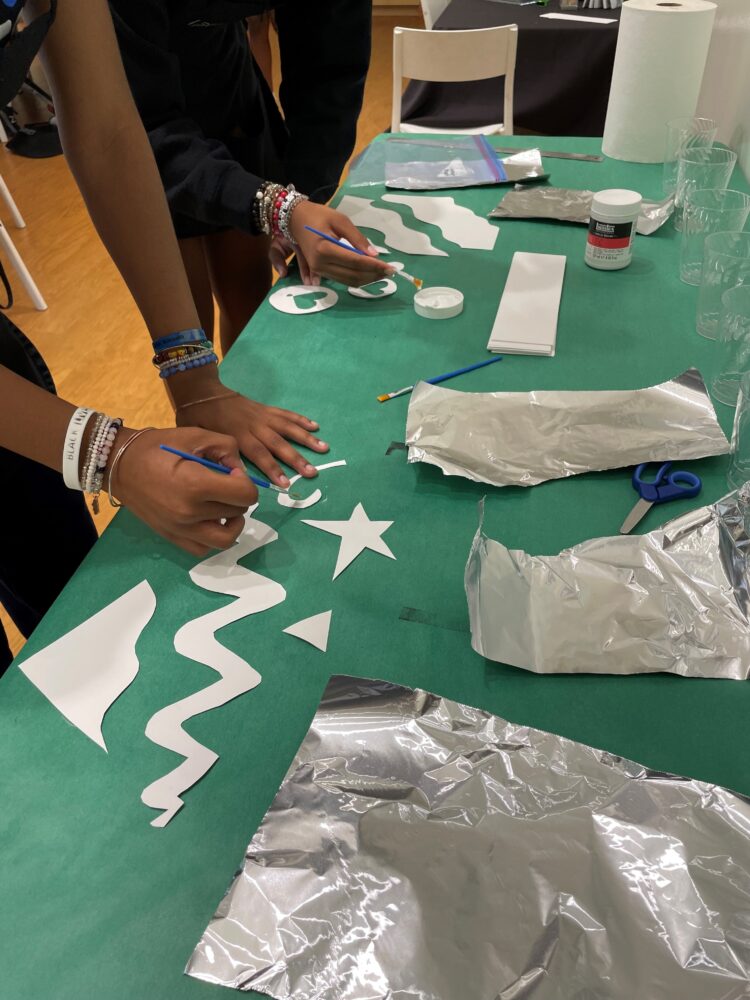

I was also able to be a part of another working group that considered issues of sustainability—in particular focusing on how to address the waste generated by exhibition and education programs. How can we create institutional policies that address and solve the waste problem? What is our responsibility to be leaders in confronting this waste problem head on?

Throughout the three days, Donna and I connected with museum professionals from around the world and heard about work that’s taking place in their museums around diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion.