Artist Ayana V. Jackson discusses her work Judgment of Paris, which premiered in Riffs in Relations: African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition, now at The Phillips Collection.

Ayana V. Jackson, Judgment of Paris, 2018, Archival pigment print on German etching paper, 40 × 60 in., Courtesy of the artist and Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Chicago

Judgment of Paris was produced in 2017 as part of Intimate Justice in the Stolen Moment, a series that looks at the black body in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

In general, my work looks at the way the black body, in particular the black woman’s body, has been represented in the history of art and popular culture as well as how it is regarded within the collective memory. Within Intimate Justice, I consider misrepresentation, absence, and exclusion. I look at what is lacking in the representation of the range of possibilities for that body. Using my body, I perform new narratives to reflect the dynamism of the black woman’s experience during that period. Obviously, if we’re talking about the 1800s and 1900s, whether it be in the Americas or other parts of the world, we are likely talking about an enslaved or colonized body, or a body in servitude. That notwithstanding, what is often left out of that frame are other modes of existence that are operating parallel to or at the very least simultaneously.

With regard to the black body in Europe and the Americas, I think it’s important for us to be very careful with the origin stories we tell and the narratives we use to associate with those bodies in that period. One can at once be enslaved and also be a mother, a sister, a lover, an idealist, a dreamer, an inventor, an engineer. These are all selves that the black body and the black woman’s body also occupied in that period of time. To this end, works like Judgment of Paris are my way of portraying the body at leisure as a counterweight to the overrepresentation of black bodies as suffering bodies in pain. It is important to consider that at any given moment, one can choose to embrace another aspect of the self.

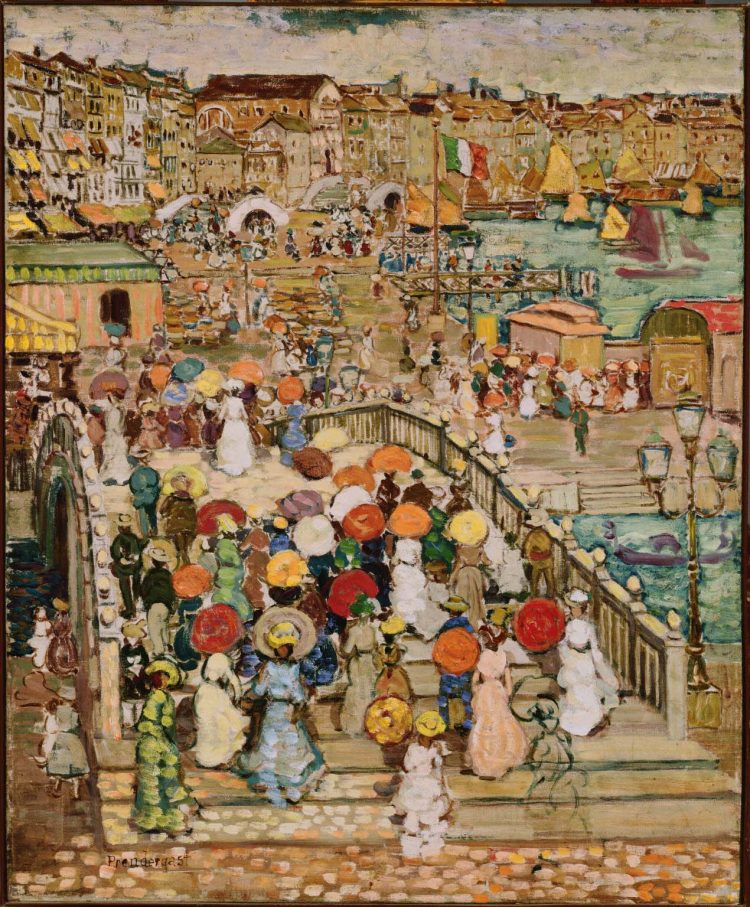

Judgment of Paris was selected for the exhibition because it refers to modernism. It references Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe, an important piece of Impressionist painting made by Édouard Manet in 1863. It may be known to many that his depiction of two dressed males and two nude and semi-nude females was quite scandalous at the time. As a result, it was rejected from the Paris Salon of 1863, though it was later included in the Salon des Refusés which was commissioned by Edward Napoleon the III.

Édouard Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1863, Oil on canvas, 82 x 104 in., Musée d’Orsay, Paris

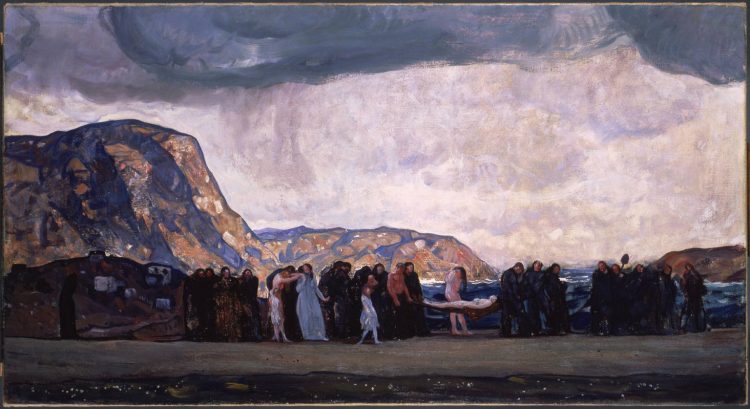

I submitted this work to the exhibition not only because of its modernist reference, but more importantly because the “original” itself is a “riff.” To some it is probably unknown that Manet was referring and perhaps sending a nod to an engraving done in the 16th century by a printmaker named Marcantonio Raimondi. This particular engraving, created in conversation with Raphael, depicts the events leading up to the Trojan War. The section that is sampled, riffed, or excerpted by Manet is found in the lower right edge of that print. There are three seated figures—two males and one female seated with her elbow on her knee.

Marcantonio Raimondi after Raphael, Judgment of Paris, c. 1515

Manet adopts this piece for Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe. I thought it would be interesting to use this work for Riffs and Relations, and initially for Intimate Justice, because Judgment of Paris—the original piece—presents Paris, the mythological character, choosing between three beauties: Juno, Minerva, and Venus. Forced to determine who is the most beautiful he ultimately chooses Venus, as portrayed in the section where he offers the apple to Venus. In considering this scene, I thought it would be beautiful to remix these two narratives and place three black women in the frame.

Manet was quite scandalous for portraying regular woman in his paintings, even worse women believed to be prostitutes in stages of undress. However, the act of bringing the non ”elite” person into the frame is part of what makes that work particularly interesting. My Judgment of Paris seeks to do the same thing—it brings the black woman’s body into a space where it is usually excluded and asks the audience to address it, look at it, and contemplate the meaning of its existence in that context.

I chose not to portray the woman’s figure nude because I didn’t find it necessary; however, I do allow for the character with her elbow on the knee to return the gaze—to confront her audience. Through that confrontation, I’m asking you to not only see the woman but also to see her absence in the history of modernism.

To that point—the topic of erasure—another detail I’d like to point out as we consider my reference material is the story of Manet’s nude in Déjeuner. Victorine Meurent is the same model in his masterpiece Olympia and at least eight of his other major works. Not only that, she was also an artist working in Paris at the time. While this has been proven to be the case, her other “selves” have largely been forgotten in favor of this mode of her existence. And she is not alone in having her agency and her other selves painted over by the brush of history. Thanks to scholars like Dr. Denise Murell, more and more of the names of women working as models during this period are coming to light, particularly black models. For instance, alongside Meurent, the woman presenting the flowers is Laure, a highly sought after and highly coveted model working at the time. She is also featured in multiple masterpieces of the era.

Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, Oil on canvas, 51 1/2 x 74 3/4 in., Musée d’Orsay, Paris

In thinking about Laure and Meurent, I am further convinced that it’s imperative for us to revisit artworks in the cannon. We should regularly reconsider how they’ve been discussed, what we focus on when we look at them, who gets to be considered. It is equally important to revisit the characters that are involved in their production and promotion. This is particularly important for those of us looking at these works from the point of view of a person who inhabits a marginalized body, a body that has been misrepresented or misjudged by history. It is incumbent upon us to judge the judges of history and reconsider their judgement. Even if it comes down through the celebrated Paris Salons of the 19th century which helped determine what is considered relevant.

Finally, I would like to add that I am super excited for the opportunity to participate in Riffs and Relations. I am incredibly grateful to Dr. Adrienne Childs for selecting me. It is not every day that an artist gets to hang alongside masters, mentors, friends, and peers. In this exhibition, Carrie Mae Weems and Renee Cox are presented—these are two women I know personally, but more importantly are artists I studied in my earliest years. Their work, as black women who work with photography and with their own bodies, has been incredibly influential. Their work on absence, their tireless placing of their bodies in spaces where it has been excluded is seminal—I learned to claim space through these two women. The opportunity to hang beside them is amazing. I am incredibly inspired by Elizabeth Catlett, and am also proud to hang alongside peers like Titus Kaphar and Hank Willis Thomas. I am perpetually in awe of their work. And, of course, it is an honor to be presented at The Phillips Collection. It is one of the most important collections in our country so to be asked to hang on their walls is a great accomplishment.

Installation view of Riffs and Relations, featuring (left to right) work by Elizabeth Catlett, Titus Kaphar, Ayana Jackson, Renee Cox, and Faith Ringgold

Lastly, I’d like to thank The Phillips Collection and its entire team for putting on this amazing exhibition, and to Dr. Adrienne Childs, I‘d like to express my deepest appreciation for her faith, confidence, and interest in my work.