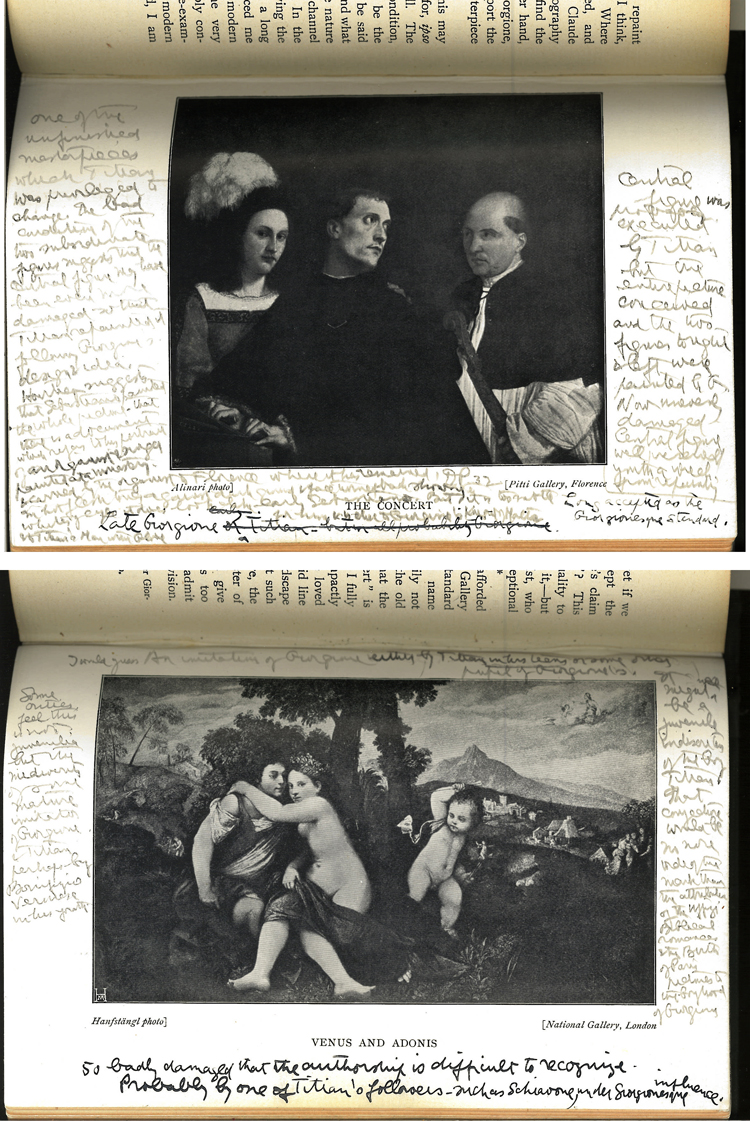

(Left) Thomas Eakins, An Actress (Portrait of Suzanne Santje), 1903, Oil on canvas, 79 3/4 x 59 7/8 inches (202.6 x 152.1 cm), Gift of Mrs. Thomas Eakins and Miss Mary Adeline Williams, 1929. The Philadelphia Museum of Art. (Right) Thomas Eakins, Miss Amelia Van Buren, ca. 1891, Oil on canvas 45 x 32 in.; 114.3 x 81.28 cm. Acquired 1927. The Phillips Collection, Washington DC.

Recently, I came across Thomas Eakins’s An Actress (Portrait of Suzanne Santje) (1903) in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and chuckled at the sight of yet another put-upon woman in a pink dress in an Eakins portrait. We’ve been having a bit of fun at the expense of Miss Amelia Van Buren (1891) who hangs on the first floor of our Sant Building as part of Made in the USA; a caption contest invites people to leave notes answering the question “What is Amelia Thinking?” But really, why are these women so down in these portraits?

Many scholars note that Eakins often aged his subjects, especially women. William J. Clark’s essay, “The Iconography of Gender in Thomas Eakins Portraiture“, claims that in photographs contemporary to the painted portrait of Santje, she is youthful, confident. Yet here, she is heavy and drained, swamped in spilling pink fabric. A portrait of her husband looms over her shoulder and a script has fallen, as if dropped from a lifeless hand, onto the floor. William S. McFeely, in his biography of Eakins, is fascinated by the Van Buren portrait and describes her dress as “ill-fitting” and “out-of-date.” She looks, presumably, outdoors and away from the gloomy interior setting. Clark compares her painted portrait to the photographs Eakins took of her in which her hair appears blonde, not streaked grey, and her skin is smooth and bright. Art historian Gordon Hendricks quotes Leonard Baskin when he suggests that Eakins was intentionally burdening women in his portraits to reflect the “Victorian horror of their lives.”

Or, maybe, it’s just that uncomfortable chair.