We’ve partnered with STABLE arts, a studio complex in DC that provides visual artists with an active workspace. STABLE artists picked a permanent collection artwork and explain how it intersects with their own practice. Visit the Phillips Instagram for more STABLE artwork.

linn meyers (@linnmeyers)

I’ve always loved Ryder’s paintings for their moodiness and surface qualities. This image resonated with me decades ago as a college student, and also later when I was in graduate school, when I was making imagined landscapes. The description in the museum’s catalogue addresses the painting’s “theme of supernatural intervention in human events and man’s helplessness in his mortal confrontation with such forces…” Given the tumultuous times we are living in today, the painting takes on new meaning for me. Who isn’t feeling a little (or a lot) helpless these days? Chaos abounds, loss of control is inevitable, and turmoil surrounds us. I continue to explore those themes in my paintings and works on paper.

linn meyers’s paintings, drawings, and site-specific works have been shown in public and private venues, including The Phillips Collection, The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, The Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, CA, The Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Art, Japan, The Corcoran Museum of Art, and more.

(LEFT) Albert Pinkham Ryder, Macbeth and the Witches, after mid-1890s, Oil on canvas, 28 1/4 x 35 3/4 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1940 (RIGHT) linn meyers, Untitled, 2019, 11 x 8.5 in., Acrylic ink on found graph paper

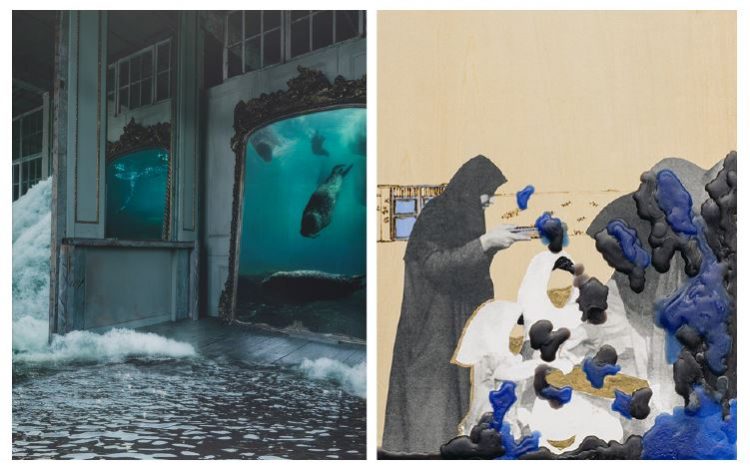

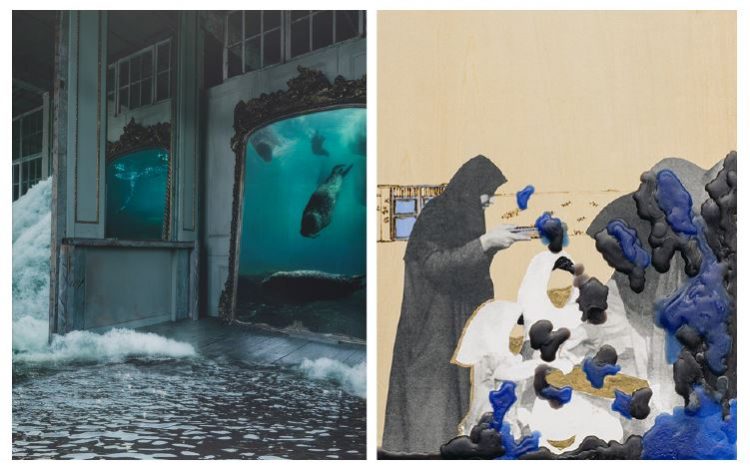

Mojdeh Rezaeipour (@mojdehr)

I’ve been working in blue a lot this past year, so I decided to choose a blue work at random! I double clicked on a link and this piece popped up—sort of like pulling a tarot card. The series “Unanswered Prayers” imagines a space that is bit by bit flooded with water, as various creatures make their way in and out of the scenes. Atmospherically, it feels like both reality and fantasy, nightmare and dream. My altar installations hold a similar space between dualities of grief and joy, destruction and creation, trauma and healing. They are simultaneously poems, prayers, puzzles.

Mojdeh Rezaeipour is an Iranian-American artist and storyteller based in Washington, DC. She is a graduate of UC Berkeley, where she studied architecture with a minor in art history, and a graduate of alt*div, an alternative divinity school centering the intersection of justice and art as spiritual practice. She is currently quarantined as an artist in residence at The Nicholson Project.

(LEFT) Anna Paola Pizzocaro, Behind the Mirror from “Unanswered Prayers” (Dall’ altra parte dello Specchio), 2010-2011, Monorail view camera and Photoshop, 47 1/4 x 37 5/8 x 1 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of the artist, courtesy of Embassy of Italy Washington DC, 2014 (RIGHT) Mojdeh Rezaeipour, Welcoming Us

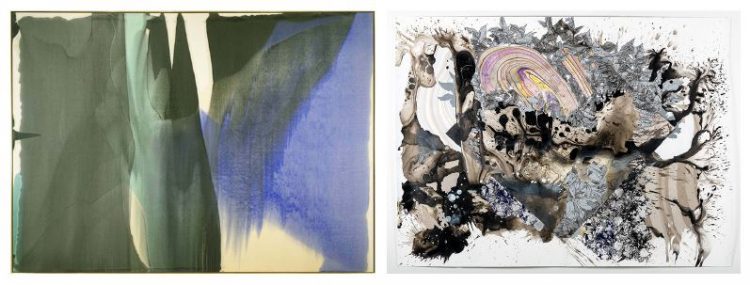

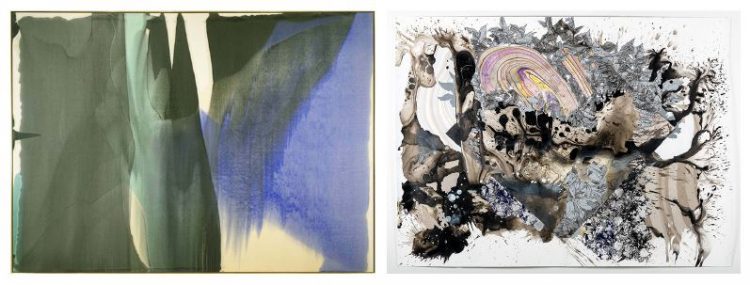

Katherine Tzu-Lan Mann (@ktzulan)

I first began pouring paint because my teacher, the force of nature and Abstract Expressionist Grace Hartigan, encouraged me to look at Color School painters like Morris Louis. At a time when we yearn for solidity and control, Louis’s work reminds us that solidity is never to be expected, and shows us the grace and poetry in fluidity and flux. This piece, created by pouring diluted paints onto canvas, is 8.5 x 12 feet, making the experience of viewing it immersive and almost cinematic. Influenced by him, other pour painters like Helen Frankenthaler, and traditional Chinese sumi ink painting, I begin every work of mine by pouring diluted paint and ink onto paper as it lays on the floor of the studio.

Katherine Tzu-Lan Mann is a painter based in Washington, DC. Her large paper paintings and installations address themes of chance, environment, mythology and identity by creating hybridized, semi-abstract landscapes. Some of the venues where Mann has shown her work include the Walters Art Museum, American University Museum, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Rawls Museum, the Art Museum at SUNY Potsdam, the US consulate in Dubai, UAE, and the US embassy in Yaounde, Cameroon.

(LEFT) Morris Louis, Seal, 1959, Acrylic on canvas, 101 1/8 x 140 3/4 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of Marcella Brenner Revocable Trust, 2011 (RIGHT) Katherine Tzu-Lan Mann, Wrap

Nekisha Durrett (@nekishadurrett)

I first saw Vik Muniz’s work in the 1990s while I was in art school. I was particularly struck by “Sugar Children”—a series of black-and-white images of black children that, from a distance, I mistook as snapshots. As I moved closer, I began to perceive texture varying accumulations of tiny grains against a black ground. A quick read of the label revealed that these were photographs of renderings of children made with sugar. A deeper read revealed that these were portraits of the children and grandchildren of sugar plantation laborers. This tension that Muniz builds between the idea, the materials used, and the viewer’s physical and psychological perspective is something that has stayed with me. Years later, I saw a short video of Muniz working in his studio. For a split second, I could see him on the floor carefully placing a butterfly with a pair of tweezers onto a lush bed of green plants and flowers. The camera panned out to reveal that this seemingly random arrangement of flowers made up the stars and bars of the American flag. That transformative moment when a small shift in perspective can make visible what is hiding in plain sight is so powerful. It is the thread that weaves through most art that I am drawn to. As I often work in disparate materials and themes, it is my hope that it is one of the threads that creates continuity within my body of work.

Nekisha Durrett lives and works in Washington, DC, where she creates bold and playful large scale installations and public art that aim to make the ordinary enchanting and awe inspiring while summoning subject matter that is often hidden from plain sight. She earned her BFA at The Cooper Union in New York City and MFA from The University of Michigan School of Art. Durrett has exhibited her work throughout the Washington, DC area and nationally.

(LEFT) Vik Muniz, American Flag (from “America Now + Here: Photography Portfolio 2009”), 2009, Digital c-print, 20 x 24 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of Carolyn Alper, 2010 (RIGHT) Nekisha Durrett, Yes Lawd

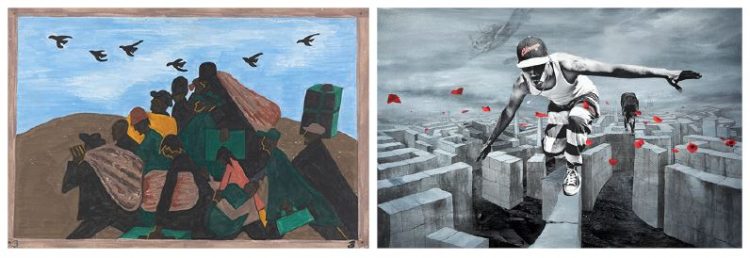

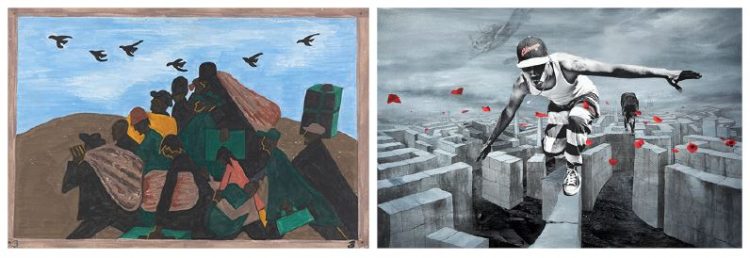

Shaunté Gates (@studio.gates)

Escaping repression in search of social mobility, my family migrated from South Carolina to DC post WWII, to find themselves entrenched in a new set of social challenges. My artwork and life are interestingly a continuation of Lawrence’s Migration Series as a whole, but particularly Panel no. 3 (contextually). How did their lives look post migration? At the crux of my work, an individual is either trying to find a way to the center or their way out of a labyrinth of social constructs. They are works about self-determination and resilience; akin to The Migration Series.

Shaunté Gates was born June 13, 1979, in Washington, DC, where he began his formal art career while studying at Duke Ellington School of the Arts. His formative years raised in a wild yet, paradoxically, beautiful DC during the eighties and nineties, created complex memories that would supply the energy and settings for his paintings and video pieces, to date. Gates is currently exhibiting works with the Smithsonian as part of a three-year traveling exhibit titled Men Of Change.

(LEFT) Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, Panel no. 3: From every southern town migrants left by the hundreds to travel north., 1940-41, Casein tempera on hardboard, 12 x 18 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1942 (RIGHT) Shaunté Gates, Dope Effect: Reagan 88

Matthew Mann (@metamuslix)

I first met this painting in the early 2000s when it was hanging near the stairs in the music room. In the 20 or so years since, I think about it maybe once a month and have stolen little bits out of it to apply to my own work almost as often. Braque to me affirms the infinite possibilities in painting and what Terry Winters says about painting being an incredibly absorbent technology. I mean, just look at all the visual material and disjointed space that Braque piled into The Washstand! The faux finished window sill, that green, bean shaped stool at the bottom, that line running through the pitcher from that trapezoidal shape stuck to the top edge…just…what?! It’s as if Braque is saying: “Psst, hey buddy! What are you worried about? It’s just painting. You can do whatever you can think to do. It will all fit.”

Matthew Mann is a painter based in Washington, DC. His paintings take inspiration from a range of visual media: quatrocento frescos, architecture, cartoons, heist films, and cultural ephemera. In Mann’s paintings these subjects flit around each other creating humorous juxtapositions and spatial incongruities that reflect his own interests in free association as well as his experiences as an artist and citizen.

(LEFT) Georges Braque, The Washstand, 1944, Oil on canvas, 63 7/8 x 25 1/8 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1948 (RIGHT) Matthew Mann, Condessa Courtyard, 2018

Damon Arhos (@damonarhos)

I chose this Francis Bacon painting Study of Figure in a Landscape because it both exemplifies and subverts the artist’s tumultuous character. Dark, vulnerable, and naked, the figure demonstrates agitation and gravity—yet, its surroundings suggest dreamlike serenity. I appreciate this duality in the composition as well as the contrast of its painterly and photographic styles. Bacon’s work aligns with mine in its concurrent presentation of conflicting visuals and narratives, those that many find concurrently attractive and disturbing.

Damon Arhos is an interdisciplinary artist, educator, curator, and social activist whose work explores and unfolds queer culture. Arhos seeks to promote love and acceptance while investigating social and political environments surrounding gender and sexuality. Arhos, who teaches studio art and art history at Bowie State University, earned an MFA in studio art at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) in Baltimore

(LEFT) Francis Bacon, Study of Figure in a Landscape, 1952, Oil on canvas 78 x 54 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1955 (RIGHT) Damon Arhos, If I Am Myself, Then Will I Be A Target? (Self-Portrait)

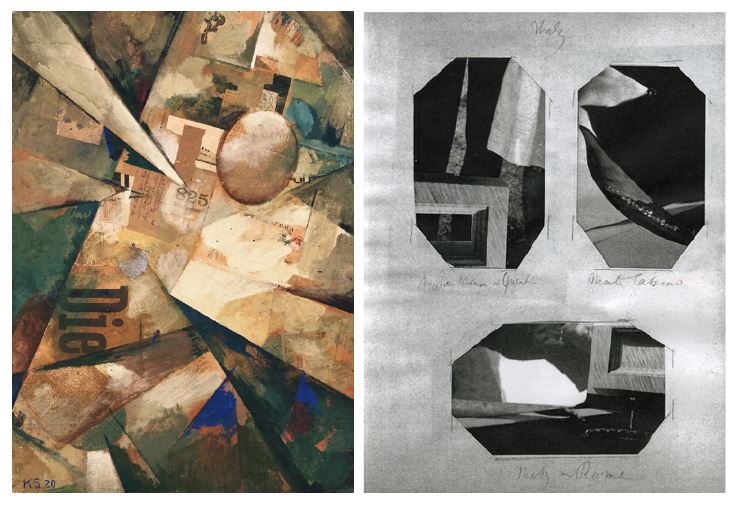

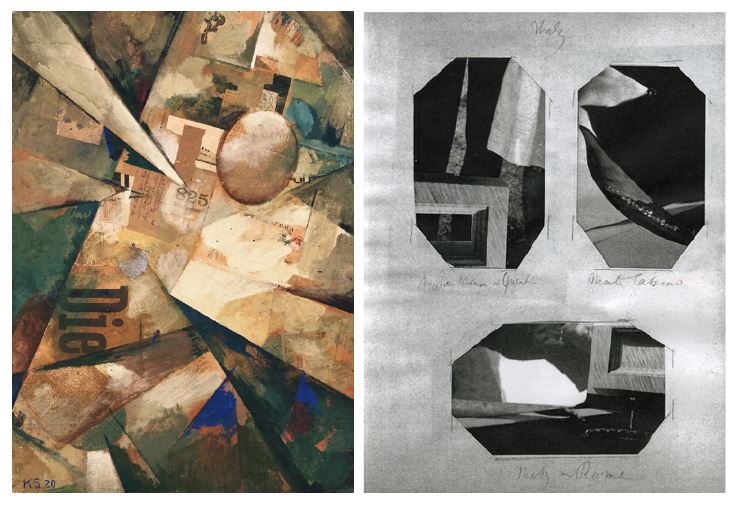

Molly Springfield (@mollyrspring)

I love the work of Dada artists—Kurt Schwitters’s collages in particular—and their use of fragmented and decontextualized language has influenced my own work. Like many of his contemporaries, Schwitters was reacting to the horrors of World War I and its resulting cultural shifts. My current project, Holograph Draft, is inspired by the life and writing of Virginia Woolf, whose work also responded to the turmoil of the early twentieth century. In addition to text-based drawings, my project includes collages made from photocopies of Woolf’s family photo albums, which in turn have inspired a new series of abstract drawings. As the project evolves, it’s become a way for me to reflect on the turmoil of our own moment and how I can best respond to it—both as an artist and as a responsible citizen of a society in the midst of a very different kind of world war.

Molly Springfield is a Washington, DC-based artist who makes drawings that use photocopies of printed text as their source material. Her work has been the subject of fourteen national and international solo exhibitions and is in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She is featured in the new book, You Are An Artist by Sarah Urist Green, released on April 14 by Penguin Books.

(LEFT) Kurt Schwitters, Radiating World (Merzbild 31B), 1920, Oil and paper collage on cardboard, 37 1/2 x 26 3/4 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift from the estate of Katherine S. Dreier, 1953 (RIGHT) Molly Springfield, Monk’s House Album III