Meet our new Director of Community Engagement Nehemiah Dixon III. Nehemiah is excited to craft a robust community engagement plan at Phillips@THEARC (where he has been part of the advisory committee since its inception) and beyond.

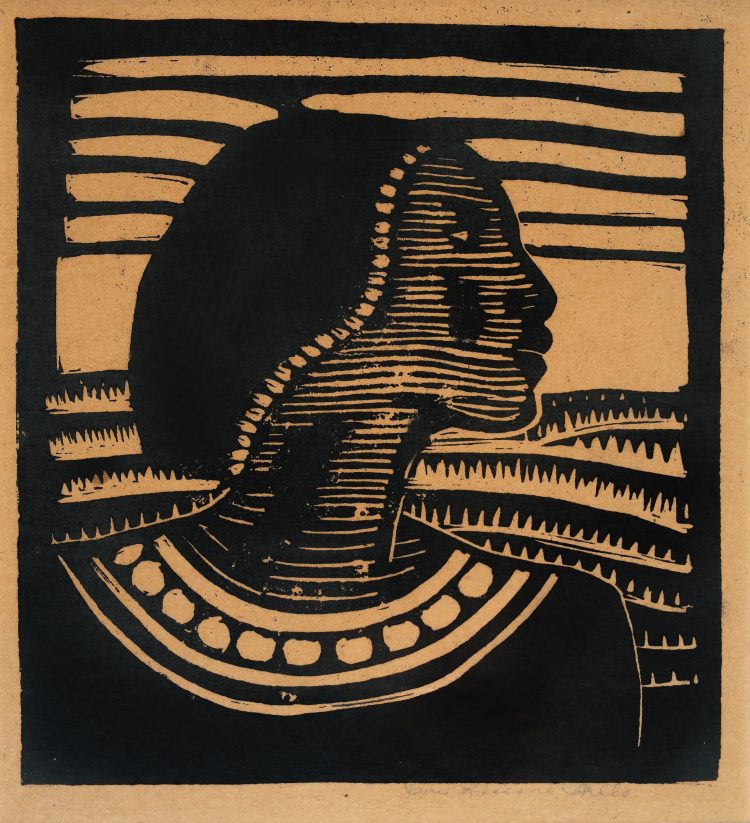

Nehemiah Dixon with Sam Gilliam’s Red Petals (1967)

Tell us about yourself!

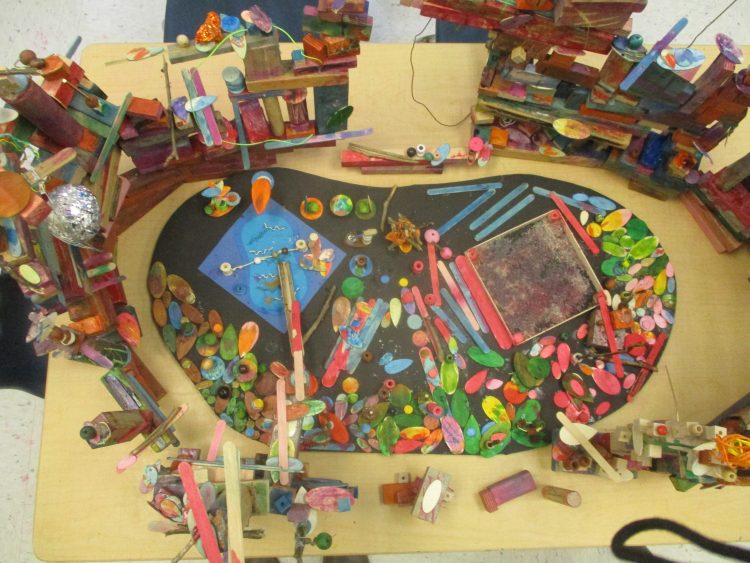

I am a native Washingtonian and proud graduate of the School Without Walls, Senior High School located on the campus of the George Washington University. My first authentic art class was a life studies class at the Washington Studio School in Georgetown, but I knew art was my passion in the fourth grade when I drew the perfect Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle. My Grandmother was an artist, who loved to make copies of Van Gogh’s and she would make these large mixed-media landscapes and display them in her all-white living room. She would take us to the Smithsonian museums on the weekend which I believe sparked my curiosity about the industry and probably directed a lot of my choices. I always knew I wanted to stay in the industry, so I graduated from the Maryland Institute College of Art with a bachelor’s degree in General Fine Arts. In 2016, I started a company called Nonstop Art where I worked with a team of artists and developers to create and manage a makerspace in an affordable housing complex. No matter what form it takes, making art and working in the arts has been and a fulfilling and rewarding career.

What excites you about working at The Phillips Collection?

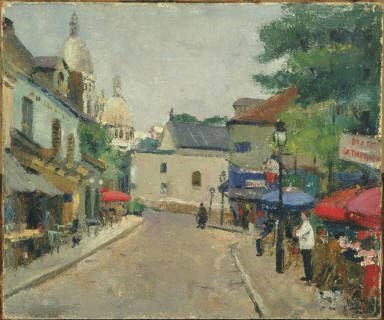

I worked at the Phillips back in 2005/2006 as a Museum Assistant. I met so many cool artists, writers, and historians, some of whom I am still friends with today. My two brightest moments were when Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party returned and I had the opportunity to witness all the fanfare and excitement around the museum with the staff and the patrons. I literally spent hours staring at that painting, engaging visitors about the historical significance of that piece. I also met Sean Scully after his artist talk at his solo show! This alone makes the Phillips avant-garde in its relationship with artists and its community. As Director of Community Engagement I am excited to work with an amazing team of scholars, artists, and educators. This is a dream come true.

What project are you most interested in working on?

There is a kid somewhere in Washington, DC, that just drew the perfect Ninja Turtle. I want to find them and bring them to The Phillips Collection. In the Spirit of Duncan Phillips’s mission to support the unknown artist in his community, I want to uphold the idea that artists and community need us. Without Duncan Phillips we might not know Vuillard. Just imagine how many people’s lives we can touch, inspire and change forever with each program, event, opening, conversation, and experience! I am most interested in hearing from the community, taking that input, and providing excellent experiences!

What would you like people to know about Phillips@THEARC?

A few weeks ago Monica Jones (Phillips@THEARC Program Coordinator), other staff members, and I held a conversation with the community about what a flag represents as part of our project State of DC (a collaboration between MidCity Development, Nonstop Art, The Phillips Collection, and DC Public Library). We used two pieces from the permanent collection, Vik Muniz’s American Flag (2009) and Jake Berthot’s Little Flag Painting (1961) as inspiration for the discussion. The discussion turned into a critique about how one flag was pristine and made using technology versus the other which was painterly and aged. One member of the community said the pristine flag belonged in “Northwest,” whereas the more rugged flag felt like “Southeast.” This important dialogue emphasized for me the importance of exposure and belonging. We are there to listen and engage with our community about what is relevant to them. What you should know is that Phillips@THEARC provides access to a catalogue of very important works of art to a historically underserved community. Our commitment to wellness and arts programming could very well improve the quality of life of the residents we serve.

Tell us a fun fact about yourself.

I am most happy making art or talking about art, or helping others make art, or planning something related to the arts—it’s a thing. Also, I almost joined the circus.