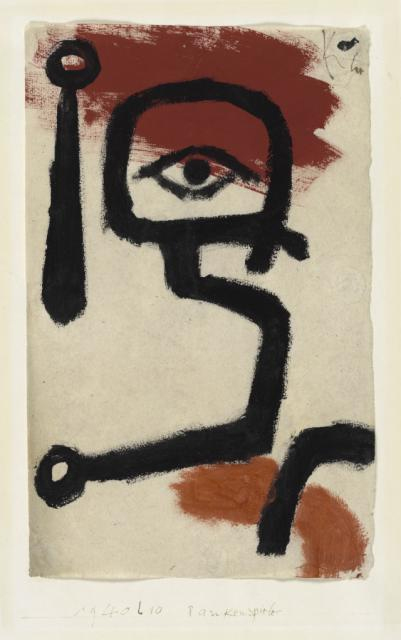

William Baziotes, Pierrot, 1947, Oil on canvas, 42 1/8 x 36 in. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1984 © Estate of William Baziotes

By the time William Baziotes painted Pierrot, he had become active in the Surrealist circles in New York centered around Chilean émigré artist Roberto Matta. A regular at Matta’s studio, Baziotes joined his colleagues Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, and others, in making drawings using the method of automatic writing, a hallmark of Klee’s practice.

Baziotes adapted automatic writing to his drawing of the character Pierrot, who emerges from a few fluid lines and broad shapes of color that meld together against an ethereal turquoise and mauve background. In his whimsical portrayal of an eye encased within three concentric bands, Baziotes suggests that there may be more to the figure than “meets the eye.” For Baziotes as for Klee, the tragiccomic clown was analogous to the modern artist. “The clown is a romantic and classical image,” Baziotes said. “The artist doesn’t want to reveal his feelings directly so he presents himself in disguise. His clothes and gestures are gay and beautiful, his face is sad.”

This work is on view in Ten Americans: After Paul Klee through May 6, 2018.