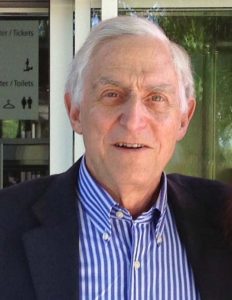

Berlin-based artist Philipp Artus speaks at the Phillips on May 11, and his work will be featured at the 2017 Contemporaries Bash: Berlin Underground. We asked the artist a few questions about his process and his work at large. Read Part 1 of the interview here.

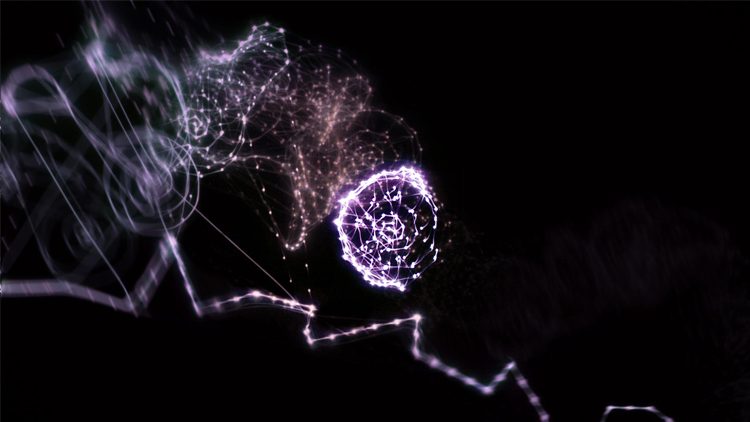

Philipp Artus, Snail Trail

I read that you take inspiration from Miles Davis. How do you go about deciding how to incorporate sound in your work? Do you have a background in music?

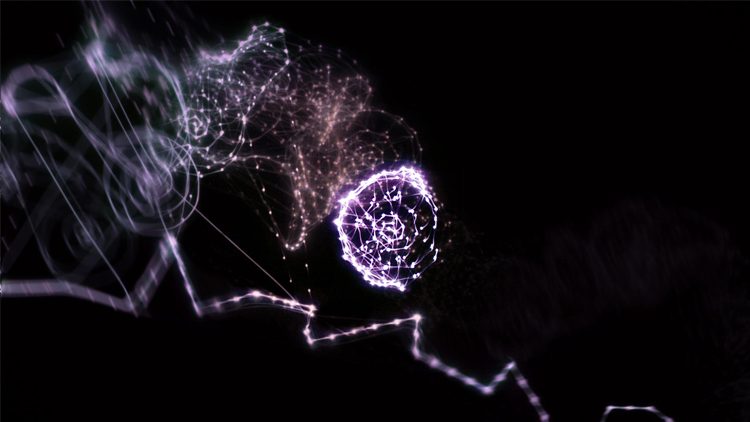

I learned to play some instruments as a kid, but I was generally more interested in drawing and photography. However, when I started studying art, I was immediately fascinated by the creative possibilities that open up through time-based art forms, like playing with rhythm, repetition, and variation. My first experiments in animation were purely intuitive, but at some point I felt the need to really understand the underlying principles I was using. Therefore, I studied Newton’s laws of motion, and also got interested in music theory, since I found that many principles of music can be applied to animation.

You mentioned Miles Davis, so let’s take him as an example. While a lot of Jazz musicians of his time were into the Bebop style, which was characterized by fast tempo and complex chord progressions, Davis was going in the opposite direction: he slowed down the pacing and concentrated more on the horizontal flow of the melody, which eventually became known as Cool Jazz.

I found that most educational books about animation give the advice to concentrate on “poses.” You would start with a particular position of a figure, then think about the next positions some frames later and so on. This “vertical” thinking about time usually leads to quick successions of character poses—which is similar to the fast chord progressions in Bebop Jazz. Miles Davis inspired me to develop a form of animation that focuses more on the horizontal flow of the movement and also to trust in the beauty of simplicity.

This example is a bit technical, but it gives you an impression of how my interest for music inspires my work. Music is essentially the art of structuring movement, which is very similar to animation.

Your current work is primarily film and animation. Have you spent any time in other mediums? If so, how does this influence your work?

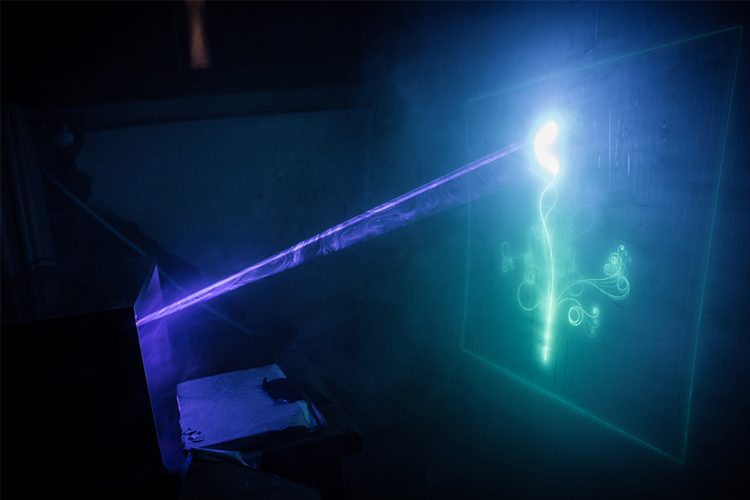

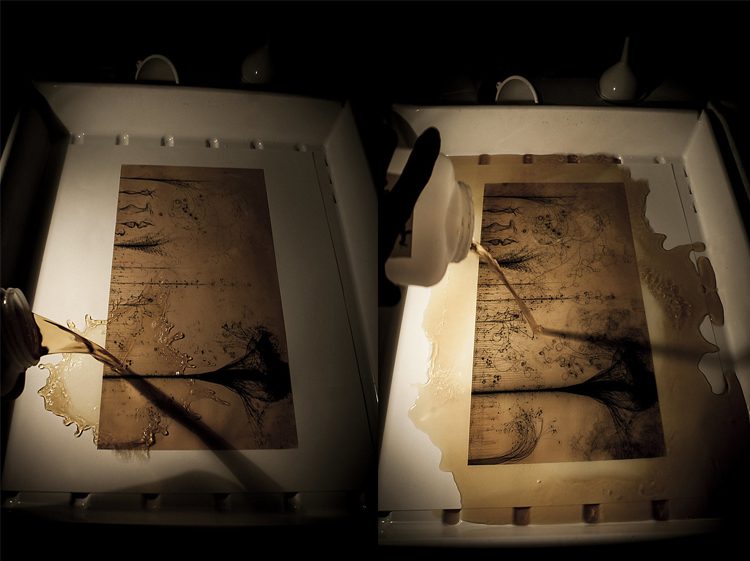

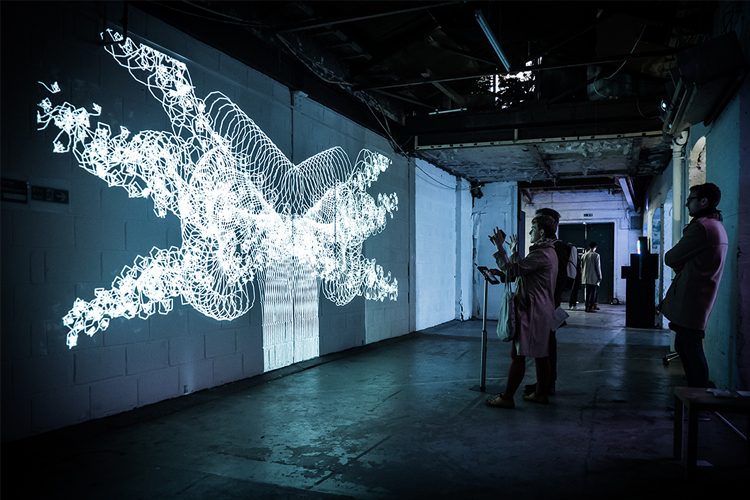

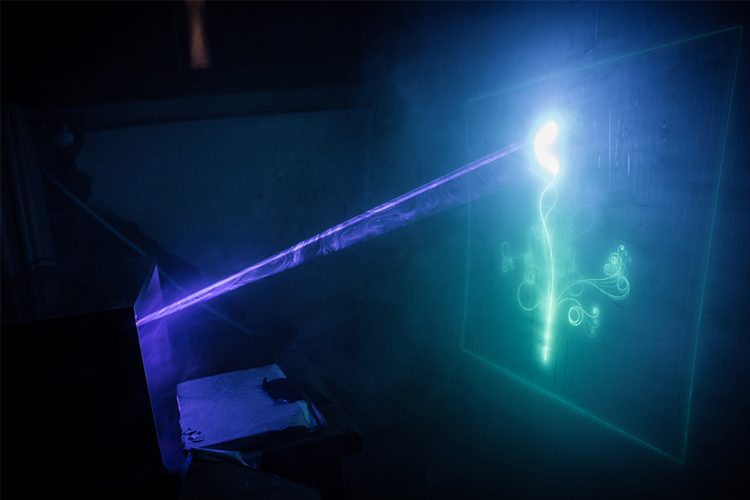

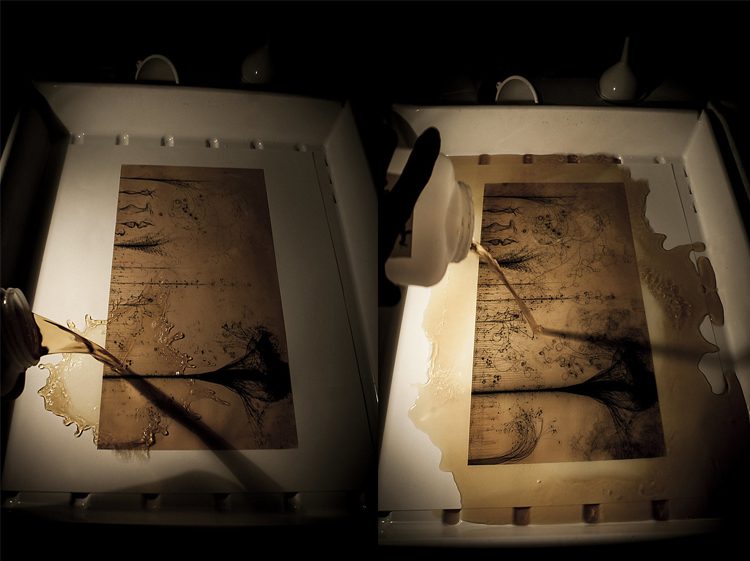

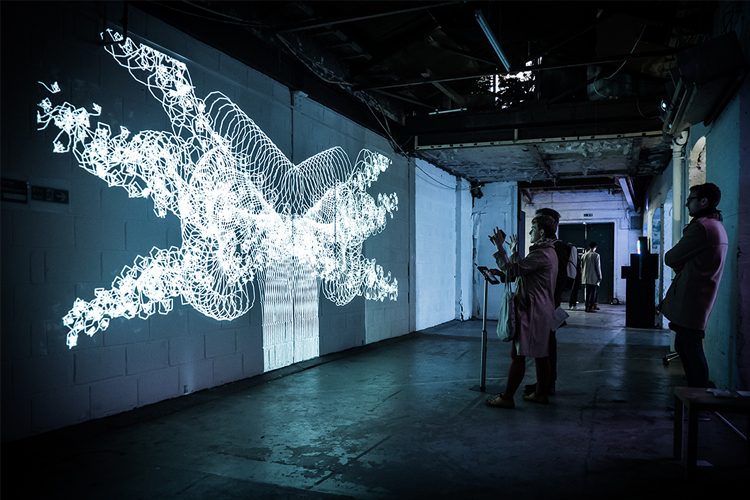

During the last two years I developed a new series of light drawings, which is the first time since the beginning of my art studies that I have worked on a “static” medium. In this series I take snapshots of the moving lines generated by the FLORA algorithm, and choose some images that become part of the light drawings series. To create these images I developed a unique printing method that combines analog photography and a laser projector. The resulting images show the traces of abstract movement frozen in time.

The photographic chemicals I am using are heavily influenced by the weather and the paper. So, in a way, this series of light drawings puts me back into the material world, which is beautiful.

Light drawings by Philipp Artus

Are there any artists, art historical or otherwise, who inform your work?

There are tons of artists who inspire my work, and it is always difficult for me to choose just a few. Two important inspirations for the FLORA light drawings I just mentioned were the plants by Karl Blossfeldt as well as the lightning fields by Hiroshi Sugimoto. Both of these photographic works are an observation of nature that avoids any kind of self-expression. This approach to art is quite far away from the selfie-obsessed society we are living in and is therefore refreshing.

However, the initial inspiration for FLORA was not a particular artist, but rather the movement of my cat’s tale. It made me realize that a simple chain of rotating joints can create a fascinating and elegant motion.

Artus’s artistic process

Your works are heavily digital. As younger generations that grew up with technology enter into the art world, what do you think is the future of digital tools as medium?

I would not say that my works are heavily digital. If you take my FLORA light drawings as an example, the shapes are generated by an algorithm in a purely digital way. But to create these images I am using an analog laser projector in combination with the chemicals of analog photography. So it is rather the interplay between digital and analog technology that I am interested in.

I think that there are quite a few artists in my generation who are interested in this dialogue between old and new media. It seems that the more we are surrounded by digital images and sound, the more we value the materiality and “aura” in analog media.

Also, digital technology makes us rediscover old technologies in new ways: The photographic process that I am using in my light drawings is called Platinotype and was invented in the 1870s. Many artists of the Pictorialist movement used it at that time, but obviously back then they neither had computer algorithms nor laser projectors.

Philipp Artus, FLORA