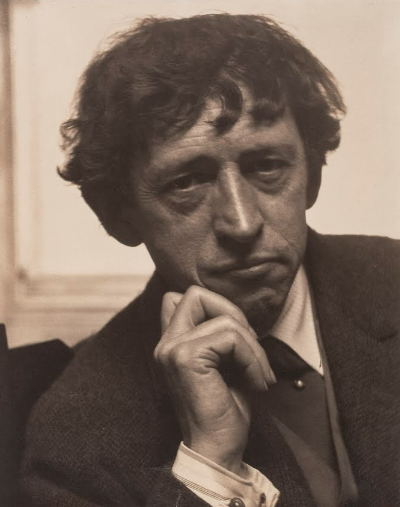

Associate Curator Renee Maurer shares letters and brochures from The Phillips Collection Archives that reveal the museum’s support of artist Jacob Kainen, one of Alma Thomas’s teachers at American University.

Trained in New York as a painter and printmaker, Jacob Kainen moved to Washington in 1942 for a curatorial job at the Smithsonian. Kainen likely met Alma Thomas at the Barnett Aden Gallery in the mid-1940s, where they would both exhibit and where she worked as vice president. In 1957, Kainen taught Thomas during her last semester at American University. A strong supporter of her art, he became a mentor and offered art critiques at her home. In his oral history Kainen said: “She asked if I would come and give her some criticism. She’d pay me. So, I came from the Smithsonian, visited her home on 15th Street, g[a]ve her criticism every couple of weeks. She’d have a little lunch there . . . . [S]he looked at everything. She really wanted to be a great painter. She not only read all the art magazines, she knew about . . . color theories, and we would discuss . . . should her stripes end before the edge of the canvas or not. We’d discuss what would happen.” Kainen and Thomas also shared an interest in the modern paintings on view at the Phillips. Kainen explained: “The big influence in this town was the Phillips Gallery on artists. . . . [Y]ou could see contemporary art, you could see modern art, you could see the connection between the older art and the new art, because the gallery was devoted to modern art and its sources.”

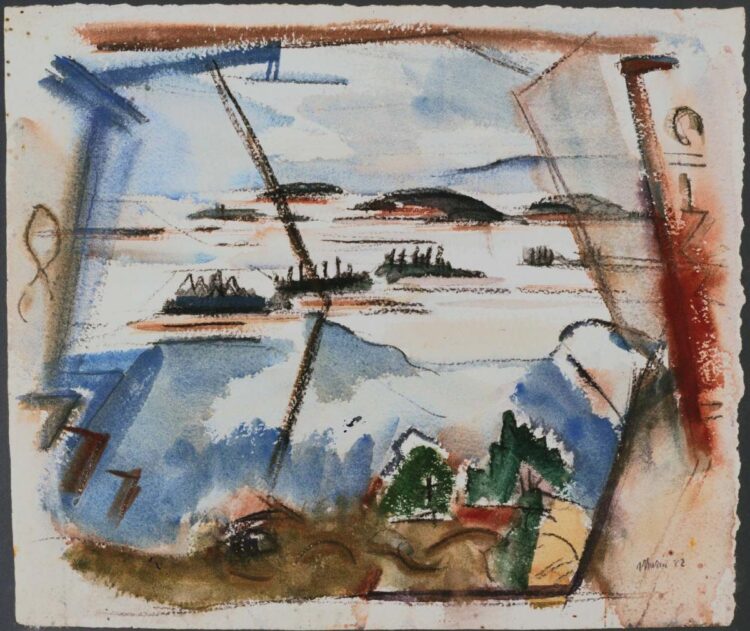

Jacob Kainen, Street Corner, 1941, Oil on canvas, 23 1/8 x 28 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1942

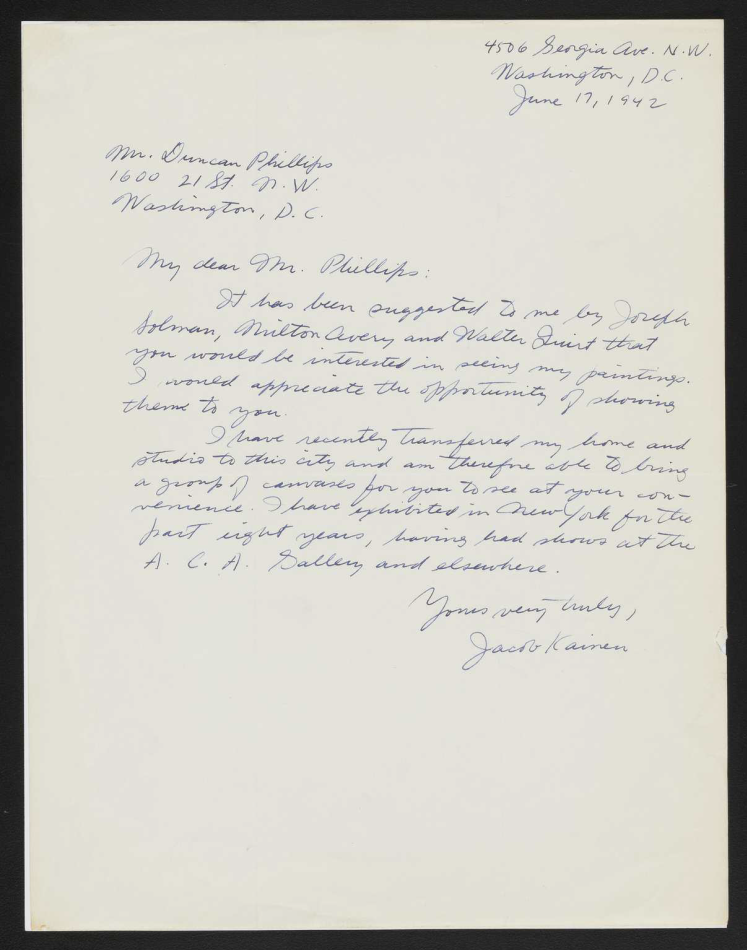

Kainen received vital support from the Phillips soon after he moved to DC. Advised by his art peers, Kainen wrote a letter of introduction to director Duncan Phillips, hoping to obtain exhibition and acquisition opportunities, as this archival letter indicates. Kainen admitted: “Phillips liked my work, said to bring some paintings up to his office, and leave them there. Duncan Phillips liked to look at paintings against the wall for weeks because he said some paintings look sensational when you see them for the first time. But when you continue looking at them from time to time they sort of fall apart . . . . Other paintings might look very modest, quiet . . . but the longer you look at them, the stronger they get.”

My Dear Mr. Phillips: It has been suggested to me by Joseph[?] Solman[?], Milton Avery and Walter Quirt[?] that you would be interested in seeing my paintings. I would appreciate the opportunity of showing them to you. I have recently transferred my home and studio to this city and am therefore about to bring a group of canvases for you to see at your own convenience. I have exhibited in New York for the past eight years, having had shows at the A. C. A. Gallery and elsewhere. Your very truly, Jacob Kainen

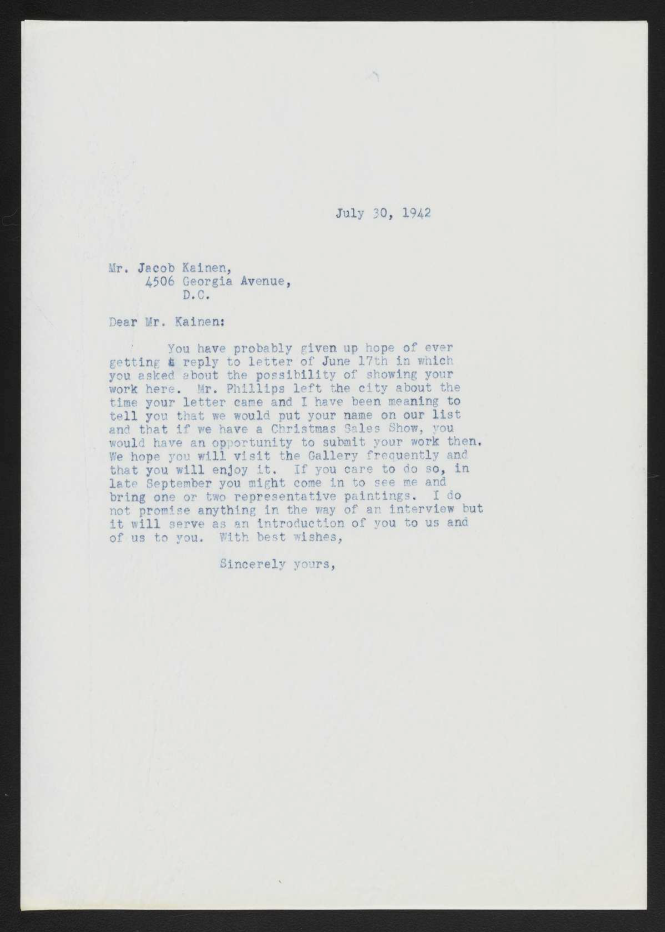

Dear Mr. Kainen: You have probably given up hope of ever getting a reply to letter of June 17th in which you asked about the possibility of showing your work here. Mr. Phillips left the city about the time your letter came and I have been meaning to tell you that we would put your name on our list and that if we have a Christmas Sales Show, you would have an opportunity to submit your work then. We hope you will visit the Gallery frequently and that you will enjoy it. If you care to do so, in late September you might come in to see me and bring one or two representative paintings. I do not promise anything in the way of an interview but it will serve as an introduction of you to us and of us to you. With best wishes, Sincerely yours,

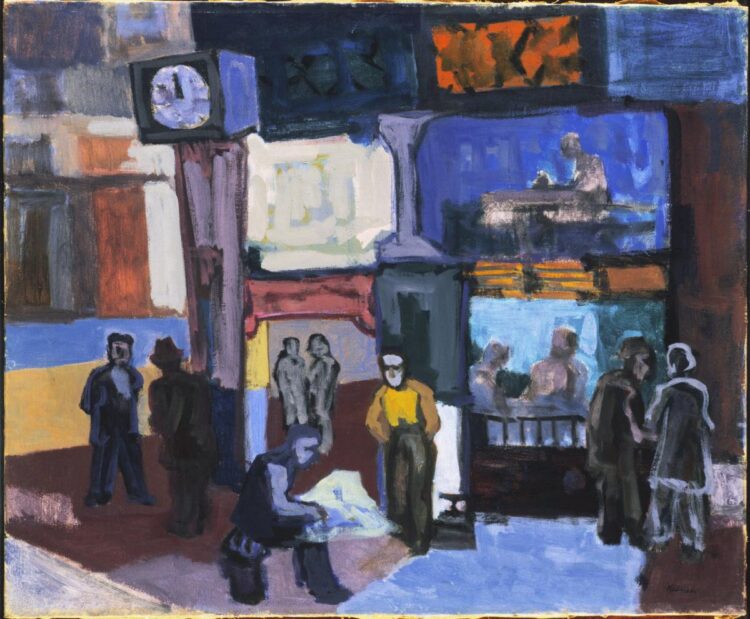

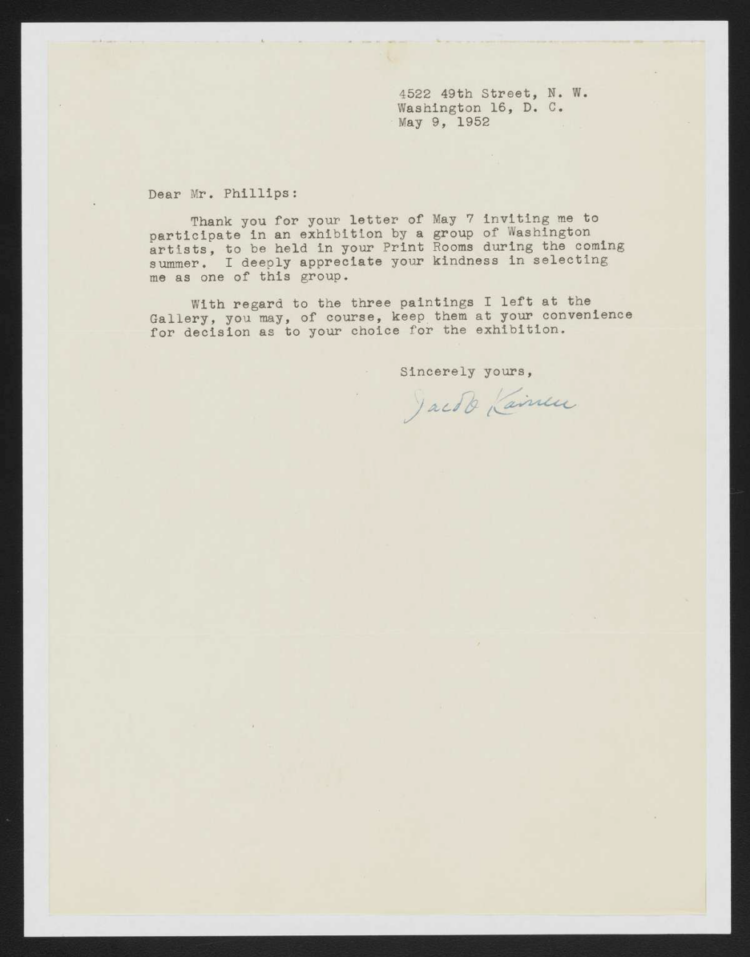

For Thomas’s teachers at American University—Kainen, Robert Gates and Ben “Joe” Summerford—the collection of modern art at the Phillips served as an important resource. In their own work and in classroom discussions, they all drew upon color-filled canvases by Pierre Bonnard, Paul Cézanne, Henri Matisse, and others at the museum. Duncan Phillips supported Thomas’s teachers in many ways through the acquisition and exhibition of their art. In 1952, the Phillips presented their work in An Exhibition of Paintings by a Group of Washington Artists, which Thomas would have seen. This letter acknowledges Kainen’s participation in the show.

May 9, 1952 Dear Mr. Phillips: Thank you for your letter of May 7 inviting me to participate in an exhibition by a group of Washington artists, to be held in your Print Rooms during the coming summer. I deeply appreciate your kindness in selecting me as one of this group. With regard to the three paintings I left at the Gallery, you may, of course, keep them at your convenience for decision as to your choice for the exhibition. Sincerely yours, Jacob Kainen

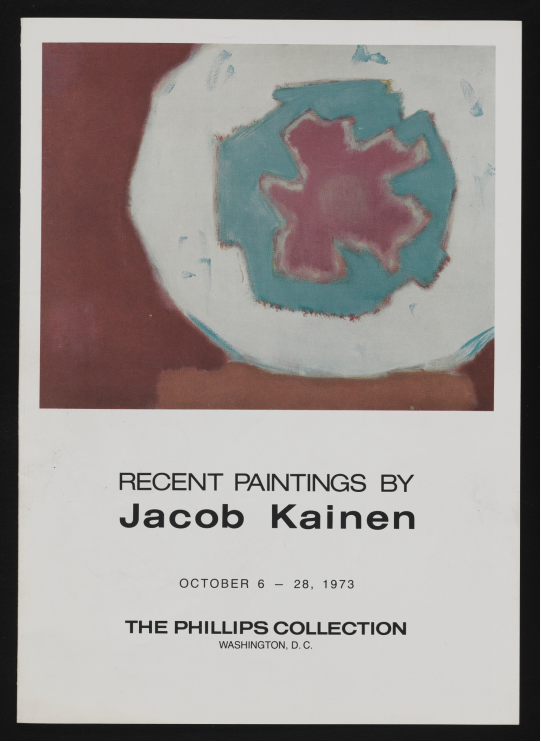

Throughout her many decades in Washington, Alma Thomas frequented the Phillips, a short walk from her home at 1530 15th Street, NW. She held onto brochures that were meaningful to her like this example from Kainen’s retrospective at museum in 1973.

Recent Paintings by Jacob Kainen exhibition brochure

NOTES:

Kainen, Jacob, 1942-1952, The Correspondence of Duncan Phillips, The Phillips Collection Archive, Washington, D.C.

https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-jacob-kainen-12620#transcript