Marilyn Mosby (@marilynmosbyesq) is an American politician and lawyer who has served as the State’s Attorney for Baltimore since 2015. She is the youngest chief prosecutor of any major American city. A few weeks ago, she visited the Phillips to immerse herself in Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle (on view through September 19), and penned this response to Panel No. 5.

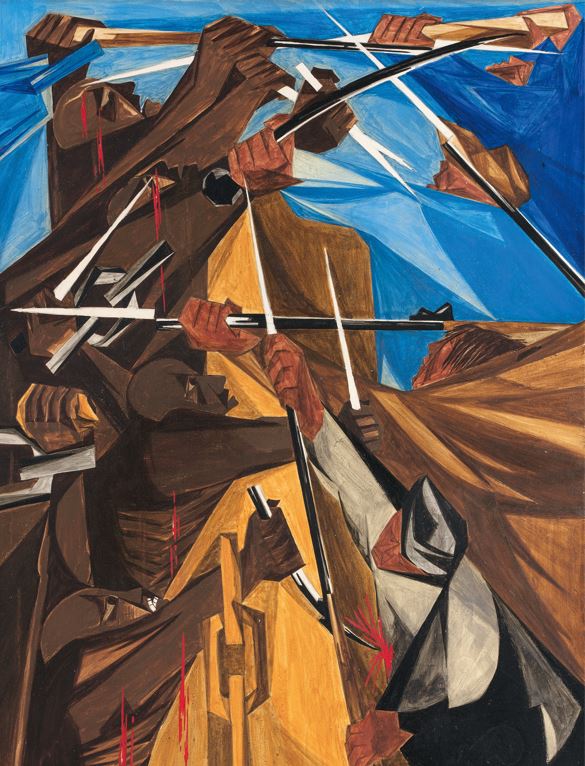

Jacob Lawrence, Panel 5: We have no property! We have no wives! No children! We have no city! No country! -Petition of many slaves, 1955, Egg tempera on hardboard, 16 × 12 in., Collection of Harvey and Harvey-Ann Ross, from Struggle: From the History of the American People, 1954–56 © 2021 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“This brilliant piece depicting the courageous rebellion of Black people in America to escape the dehumanization of slavery is powerful. No man should be denied the most basic fundaments of freedom based on the color your skin, yet Jacob Lawrence radiantly illustrates the bloody struggle, the immoral resistance, and the courage it took to fight for the humanity of Black people to be seen.

The painting’s title We have no property! We have no wives! No children! We have no city! No country! is taken from the petition of many slaves, but it is just as easily a cry that could be made today by the many people of color who are imprisoned in this country. Just like slavery, when you go to prison, this country does not see your humanity and you lose your property, your family, your right to vote, and so much more. It is to our nation’s enduring shame that we currently have more Black people under lock and key than we ever did under slavery. We’ve exchanged one set of chains for another—the chains of mass incarceration. It is a system I have dedicated my life to upending, and it is my hope that one day we will win that struggle. Yet for now, this painting reminds me that sadly, the more things change, the more things stay the same.”

—Marilyn J. Mosby, State’s Attorney for Baltimore City