Director of Community Engagement Nehemiah Dixon III shares his experience as member of Red Dirt Studio, a new Phillips Collection partner.

A few weeks ago I was invited to participate in a talk with The Phillips Collection’s Contemporaries group. The invitation came from Margaret Boozer, the founding Co-Director of Red Dirt Studio of which I have been a member since the spring of 2015. So I sat with my studio mates and we talked with the Contemporaries about the work we do and the art we make.

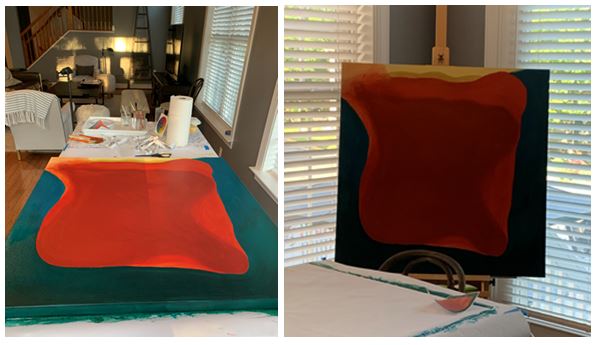

What I shared is that the art I make is unquestionably linked to the times we live in. What started as my response out of frustration and grief from the blatant disregard for the life of Trayvon Martin has echoed over the years as an immutable recurring nightmare. My Hoodies represent what others see of me and of the fear I have of navigating a world that does not respect my life. They represent the hollow attempts of mitigating racism, police brutality, implicit bias, and the stereotyping of over policed brothers and sisters I call family. My Hoodies are my pain in the form of sculpture.

Working at Red Dirt on my Hoodies sculptures created with epoxy and resin

Suits of Armour installed in Foggy Bottom as part of the Foggy Bottom Sculptors Biennial

Red Dirt Studio sits on the border of Washington, DC, in a small town called Mt. Rainier, nestled in the Gateway Arts District which is home to many artists, makers, and community shakers. Finding this community has been my school after school and my artist home away from home for over ten years. The education I have gained from friendships and community building that takes place there has been paramount to my career as an artist and administrator.

Red Dirt is where I make art but much more than that it is where we develop each other and push each other to work harder and smarter. It is where we meet on Saturdays to have Seminar (now on Zoom called Zoominar) to share, critique, and create business. It is where—when safe to do so—we hold community events such as our yearly Open Studio Tour, fundraisers, and gallery shows. It is grad school without pocket-busting tuition and an incubator for ideas, projects, and goals. Red Dirt is home for 30 artists, arts administrators, sculptors, photographers, landscape architects, painters, and more.

A pre-covid in-person Seminar

This summer, the Phillips’s Education and Community Engagement Department has been partnering with Red Dirt Studio to present a series of free online workshops every other Saturday called Hands-on with Red Dirt. The artists hone their presentations in Seminar and then meet with the Community Engagement team to further develop the concepts for the event. Each week the series features an artist who walks participants through an activity, which has ranged from creating your own chakra color wheel to creating your own shadow boxes using found objects.

If you would like to experience what being at Red Dirt Studio is like, sign up for a Saturday workshop!