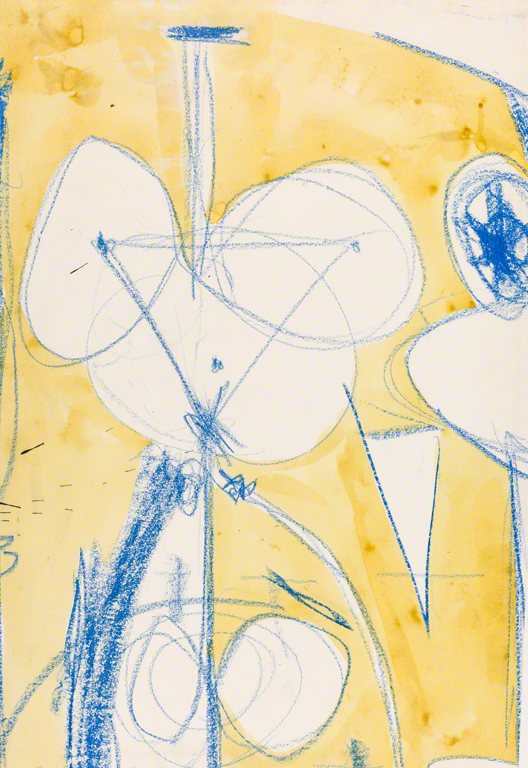

Robert Motherwell, Concept of Woman, 1946. Crayon and watercolor on paper, The Phillips Collection, Gift of Louis and Susan Stamberg, 2014

“One of my natural talents that I don’t use enough in painting is line and paint both. I guess the closest example, though he does miniatures compared to what I do, is Paul Klee.”—Robert Motherwell

obert Motherwell had extensive contact with Paul Klee’s art, both in reproductions in books he owned, as well as in the “hundreds of Klees” he saw in exhibitions in New York. Professing his admiration for Klee as a “supreme doodler,” Motherwell equated doodling to automatic drawing, a method he was first introduced to by Surrealist Roberto Matta in 1941. “I think doodling is strictly one of the alternative ways of drawing. So far as I know, every Paul Klee, after his maturity, invariably began with doodling.”

In his witty Concept of Woman, Motherwell exploits his talent as a doodler in both line and color. Doodling was, however, only the first step in a dynamically evolving process Motherwell called “the automatic and formal beauty that is the end result of an emerging process.” In Concept of Woman, Motherwell begins the composition with freely drawn lines and circular forms that eventually achieve a structural rhythm evocative of a female figure. The “real content” of painting, Motherwell argued, was an expression of a person’s mysterious and elusive qualities, perhaps an aspect that underlies this work’s evocative title.

This work is on view in Ten Americans: After Paul Klee through May 6, 2018.